Violence against women: the EU’s potential accession to the Istanbul Convention

Half of the EU member-states have not yet ratified the Convention on violence against women. The European Parliament and the Commission have decided that the EU as such should adhere to the Convention, which could signal a breakthrough for a genuine European policy against violence

Exactly six years have passed since the signing of the Istanbul Convention on violence against women, yet half of the EU member-states have still not ratified the treaty. In the next few months, however, things could change, thanks to a new series of ratifications, and above all thanks to the possible accession of the EU as such to the Convention. The accession has been proposed by the European Commission and is strongly supported by the Parliament, which in recent weeks has turned to discuss the topic, while awaiting a resolution to negotiations within the Council of the EU.

The eventual accession of the EU to the Istanbul Convention would join rather than replace individual states’ accession to the Convention. It should in the first place cover the areas of competence of European institutions, which deal for example with the rights of victims and migrants, and cooperation in criminal law. The accession of the EU would furthermore serve to improve the efficacy and coherence of national policies against gender based and domestic violence, which are still rather diverse. According to the European Parliament , the accession of the EU to the Istanbul Convention should favour the development of a comprehensive European strategy against gender based violence and inequality.

What is the Istanbul Convention?

The Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence is a treaty developed by the Council of Europe, signed in Istanbul in 2011, and put into force in 2014. The Council of Europe is independent of the EU, and particularly concerned with human rights, democracy and rule of law – it is the organisation which, among other things, holds the European Convention on Human Rights, and the Court which ensures its respect. The Council of Europe does not just consist of EU member-states, but also states from the Balkans, the Caucasus and Eastern Europe: the Convention on violence against women was signed by 44 states.

The Istanbul Convention is the first international treaty specifically aimed at combating violence against women, and providing precise legal obligations to the adhering countries. While insisting on the necessity of effectively prosecuting violence from the view of criminal law, the Convention takes a comprehensive view of violence, its roots and the ways to fight it, suggesting that authorities and civil society should have recourse to a full range of tools, even economic, social and cultural.

The slow pace of ratification

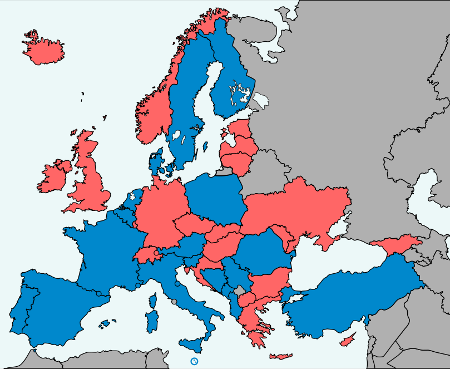

The ratification of international treaties is often a slow process: some governments sign treaties on human rights as a response to outside pressure and to appease public opinion, but defer the moment of ratification, which makes the agreements binding. As of today, the Istanbul Convention has been ratified by 14 out of 28 EU countries. The process has been on average faster among states to the West, but with some notable exceptions: Poland and Romania ratified the Convention well before Germany and the UK.

The Istanbul Convention is of immediate judicial relevance, and therefore many states, before ratifying the Convention, need to adapt their penal code and other rules regarding violence, so that they are in line with the Convention’s definitions and commitments. Some delays are, however, due to political reasons, rather than technical – for example, the polemic around the concept of “gender” and the calling into question of gender stereotypes, fuelled above all by conservative Catholic circles.

On the other hand, in recent months there has been a new reluctance to intervene in decisions regarding violence against women – a reluctance fuelled by the decriminalisation of some forms of domestic violence in Russia, and the calling into doubt of certain rights of women in Turkey, Poland and other countries. In asking member states to ratify the treaty, the European Parliament requests that they adhere fully to the agreement, and not avoid the less welcome demands.

Violence against women in the EU

The European Commission has decided to dedicate 2017 to combating violence against women, launching a campaign on the issue and allocating appropriate funds. Noting the diversity of national contexts, however, the campaign relies on the initiative of individual states. One of the obstacles facing a truly European approach to the question is precisely the lack of uniformity in the definition of violence against women – an obstacle that the Istanbul Convention should help to remove.

In 2014 the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights published research that, together with the Eurobarometer of 2016, provides an empirical base on which to found a European initiative against violence. According to this research, “In Europe one woman in three has suffered physical or sexual violence at least once in her adult life, […] one woman in five (18%) has been a victim of persecution, one in twenty has been raped, and more than one in ten have suffered sexual violence involving lack of consent or the use of force.” There is also an estimate of the economic cost of violence against women: 230 billion euro per year.

The EU and the other Conventions on rights

The EU has for decades discussed the possibility of adhering directly to the European Convention on Human Rights, which is individually ratified by all member-states. While the Lisbon treaty provides accession to the European Convention, negotiations reached an impasse in 2014, after a negative opinion from the EU Court of Justice. The competence of European institutions in protecting fundamental human rights within the EU has been repeatedly challenged, starting with the UK, and more recently with the cases of Hungary and Poland.

The defence of individual rights and the fight against discrimination therefore still remain areas reserved for nation-states, or at most delegated to the Council of Europe: the accession of the EU to the Istanbul Convention would signal important progress for European institutions’ activity in this area. A first step in this direction took place in 2010, when the European Union ratified the UN Convention on persons with disabilities. Already in that case the accession of the EU existed alongside the accession of individual states, guaranteeing respect for the Convention with regard to European – rather than just national – policy.

Online course on anti-discrimination

Anti-discrimination is a fundamental right in the European Union. To learn more on EU anti-discrimination policies and their impact check our online course "The Parliament of Rights"

Tag: Women

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Violence against women: the EU’s potential accession to the Istanbul Convention

Half of the EU member-states have not yet ratified the Convention on violence against women. The European Parliament and the Commission have decided that the EU as such should adhere to the Convention, which could signal a breakthrough for a genuine European policy against violence

Exactly six years have passed since the signing of the Istanbul Convention on violence against women, yet half of the EU member-states have still not ratified the treaty. In the next few months, however, things could change, thanks to a new series of ratifications, and above all thanks to the possible accession of the EU as such to the Convention. The accession has been proposed by the European Commission and is strongly supported by the Parliament, which in recent weeks has turned to discuss the topic, while awaiting a resolution to negotiations within the Council of the EU.

The eventual accession of the EU to the Istanbul Convention would join rather than replace individual states’ accession to the Convention. It should in the first place cover the areas of competence of European institutions, which deal for example with the rights of victims and migrants, and cooperation in criminal law. The accession of the EU would furthermore serve to improve the efficacy and coherence of national policies against gender based and domestic violence, which are still rather diverse. According to the European Parliament , the accession of the EU to the Istanbul Convention should favour the development of a comprehensive European strategy against gender based violence and inequality.

What is the Istanbul Convention?

The Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence is a treaty developed by the Council of Europe, signed in Istanbul in 2011, and put into force in 2014. The Council of Europe is independent of the EU, and particularly concerned with human rights, democracy and rule of law – it is the organisation which, among other things, holds the European Convention on Human Rights, and the Court which ensures its respect. The Council of Europe does not just consist of EU member-states, but also states from the Balkans, the Caucasus and Eastern Europe: the Convention on violence against women was signed by 44 states.

The Istanbul Convention is the first international treaty specifically aimed at combating violence against women, and providing precise legal obligations to the adhering countries. While insisting on the necessity of effectively prosecuting violence from the view of criminal law, the Convention takes a comprehensive view of violence, its roots and the ways to fight it, suggesting that authorities and civil society should have recourse to a full range of tools, even economic, social and cultural.

The slow pace of ratification

The ratification of international treaties is often a slow process: some governments sign treaties on human rights as a response to outside pressure and to appease public opinion, but defer the moment of ratification, which makes the agreements binding. As of today, the Istanbul Convention has been ratified by 14 out of 28 EU countries. The process has been on average faster among states to the West, but with some notable exceptions: Poland and Romania ratified the Convention well before Germany and the UK.

The Istanbul Convention is of immediate judicial relevance, and therefore many states, before ratifying the Convention, need to adapt their penal code and other rules regarding violence, so that they are in line with the Convention’s definitions and commitments. Some delays are, however, due to political reasons, rather than technical – for example, the polemic around the concept of “gender” and the calling into question of gender stereotypes, fuelled above all by conservative Catholic circles.

On the other hand, in recent months there has been a new reluctance to intervene in decisions regarding violence against women – a reluctance fuelled by the decriminalisation of some forms of domestic violence in Russia, and the calling into doubt of certain rights of women in Turkey, Poland and other countries. In asking member states to ratify the treaty, the European Parliament requests that they adhere fully to the agreement, and not avoid the less welcome demands.

Violence against women in the EU

The European Commission has decided to dedicate 2017 to combating violence against women, launching a campaign on the issue and allocating appropriate funds. Noting the diversity of national contexts, however, the campaign relies on the initiative of individual states. One of the obstacles facing a truly European approach to the question is precisely the lack of uniformity in the definition of violence against women – an obstacle that the Istanbul Convention should help to remove.

In 2014 the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights published research that, together with the Eurobarometer of 2016, provides an empirical base on which to found a European initiative against violence. According to this research, “In Europe one woman in three has suffered physical or sexual violence at least once in her adult life, […] one woman in five (18%) has been a victim of persecution, one in twenty has been raped, and more than one in ten have suffered sexual violence involving lack of consent or the use of force.” There is also an estimate of the economic cost of violence against women: 230 billion euro per year.

The EU and the other Conventions on rights

The EU has for decades discussed the possibility of adhering directly to the European Convention on Human Rights, which is individually ratified by all member-states. While the Lisbon treaty provides accession to the European Convention, negotiations reached an impasse in 2014, after a negative opinion from the EU Court of Justice. The competence of European institutions in protecting fundamental human rights within the EU has been repeatedly challenged, starting with the UK, and more recently with the cases of Hungary and Poland.

The defence of individual rights and the fight against discrimination therefore still remain areas reserved for nation-states, or at most delegated to the Council of Europe: the accession of the EU to the Istanbul Convention would signal important progress for European institutions’ activity in this area. A first step in this direction took place in 2010, when the European Union ratified the UN Convention on persons with disabilities. Already in that case the accession of the EU existed alongside the accession of individual states, guaranteeing respect for the Convention with regard to European – rather than just national – policy.

Online course on anti-discrimination

Anti-discrimination is a fundamental right in the European Union. To learn more on EU anti-discrimination policies and their impact check our online course "The Parliament of Rights"

Tag: Women