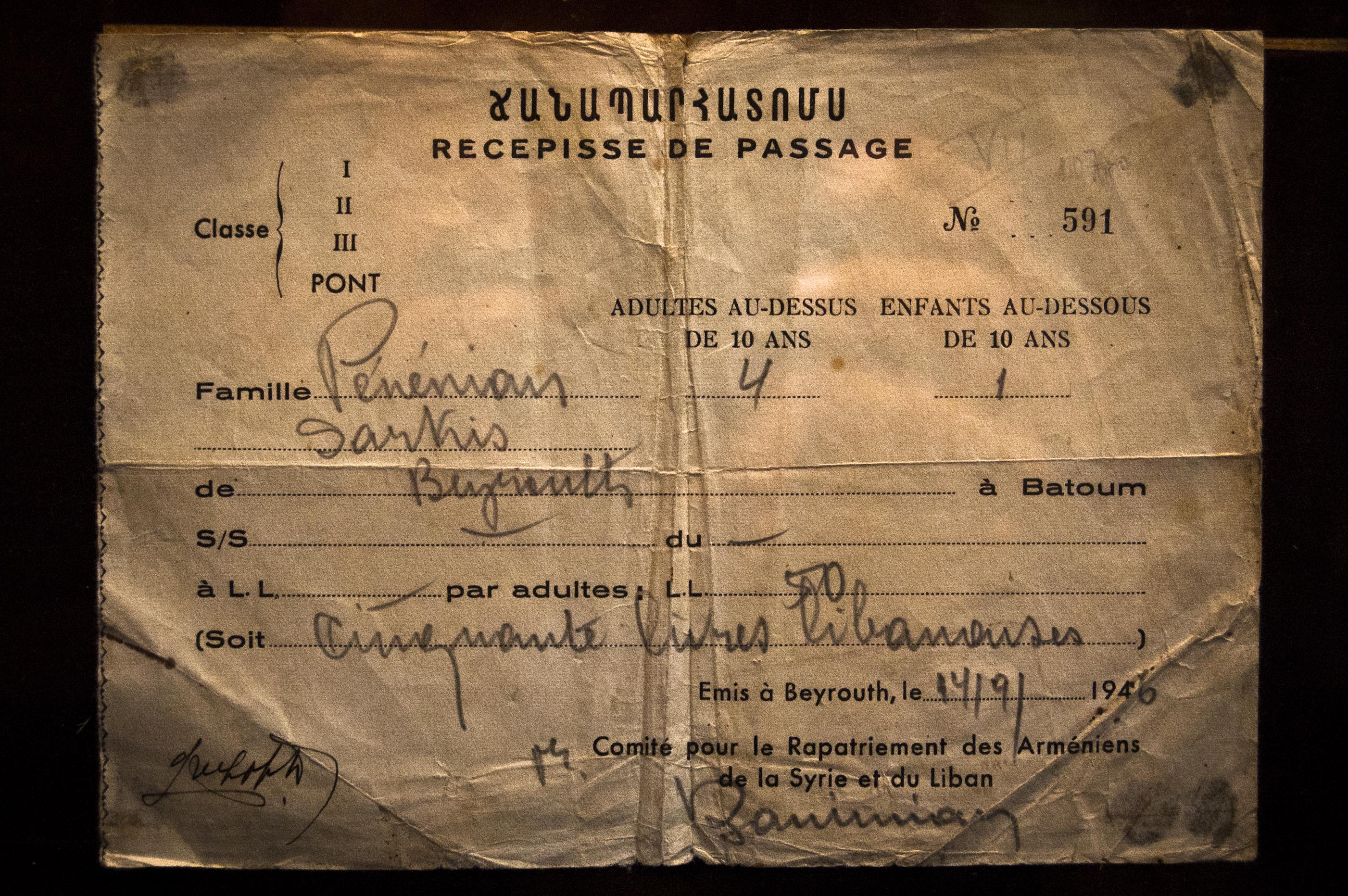

Mussa Dagh Museum - Boarding pass for Armenia 1948, photo by Paolo Martino

Vartuhi left Beirut in 1946, to reach Soviet Armenia aboard a ship called "Pobeda". In Stalin's land, however, the survivors of the genocide saw the dream of a homeland turn into a nightmare. Travelling to the Caucasus on the paths of migrations. Fourth episode of the story "From the Caucasus to Beirut"

“To overcome the censorship of the Soviet regime, we used code messages. ‘The bread is good’ meant we were starving. ‘The wardrobe door is broken’ meant persecution, imprisonment. If in a picture there were people lying down, it meant someone had died, and so on”. In her apartment in the centre of Anjar – three thousand Armenians up in the Lebanese mountains, Angel goes over the thread of family memories dating back to over 60 years ago, when her sister Vartuhi left Lebanon to move to Soviet Armenia. “Right from the early letters, all that was written about was bread and wardrobes, then the pictures also slowly started coming in. I realised that Armenia was not the heaven the Russians wanted us to believe. And that I would never see my sister again”.

Palestinian anonymous“Refugees are

the tears of war”

Following World War II, the Armenian diaspora was faced with yet another challenge. Determined to rebalance the demographic gap left by the millions of casualties from the war, the Soviet Union promoted huge repopulation campaigns. Anxious to finally be in a “motherland” of their own, American, European and Middle-Eastern Armenian communities, moved en masse. Starting from 1946, trains, ships and convoys with the red star moved thousands of children of the Armenian diaspora to Yerevan, in Soviet Armenia. Seventy percent of Anjar’s inhabitants, 3.500 out of 5.000, chose to leave. Among these was Vartuhi, Angel’s sister.

“It was very hard, at the beginning. Lebanese Armenians were used to moving, reading the newspaper, speaking their minds, so they were immediately spotted by the merciless eye of the regime. Many were shipped to Siberia, to concentration camps”. Angel’s memory moves smoothly to distant seasons, sweeping through the immeasurable geography of the diaspora as if no corner of the world were unknown.

“But Anjar’s Armenians are thick-skinned. Slowly, they built their lives, their homes, even a village, close to Yerevan”. I interrupt her. “Is this village still there?”. Angel smiles: “Of course. It’s called Musa Dagh. Just like our native land. My sister lives there”. Enraptured by her memories, the old lady recounts the years of her youth, of the irreversible choices, while in my mind, a blurred idea is becoming clearer and clearer. While saying goodbye to Angel the Lebanese way, with three kisses on the cheek, I take a picture of her and make her a promise: “I will come back to see you, with a surprise”.

From my diary. 3rd November

The stream of memory that links the Caucasus to the Middle-East flows just under the surface of everyday life. The Inhabitants of Musa Dagh who leave Turkey in 1939 to move to Lebanon travel to Armenia eight years later. One-way journeys, decisions without appeal, but each displacement marks the land, tracing a path that from the Caucasus leads to Beirut and viceversa.

Vakif, the only one of the seven villages of Musa Dagh that chose to remain under Turkish authority, still inhabited by Armenians; Anjar, the Armenian jewel in the Bekaa valley, a pacific oasis in one of the world's most conflict-ridden areas; the new Musa Dagh in Yerevan’s suburbs, a refuge for those who in 1946, after so much misery, thought they had finally found the road to the Rising Sun of the Future. Splinters getting lost in the tragedy of the genocide, in games between powers, among the ruins of the wars of the Middle-East and the Caucasus. The only way to get back to the human element, to understand the choices of the many Vartuhis and Angels of this story, is to walk on the paths of those migrations, measure them with one's steps, with the rain and the monotonous horizons of the plateau and the desert.

“I’m going to Yerevan, I already have a ticket”. Sitting as usual in front of the shutters of the shoe factory, Rafi blows the dense smoke of the Turkish pipe unperturbed. “I knew you would leave, one day or another. You have become paranoid in your search for a rational logic in the history of my people. In time, you will learn it’s not worth it”. Rafi screams something in Armenian to a boy, who immediately serves us arak, an aniseed liquor diluted with water and ice. A one-dollar tip and the boy disappears, swallowed up in the chaos of Burj Hammoud, the Armenian quarter in the heart of Beirut. “What are you going to Armenia for?” While the night is falling on the alley, Rafi listens to the story of Vartuhi and Angel, the sisters separated by the Pobeda, the ship that in 1946 moved thousands of Lebanese Armenians beyond the Iron Curtain. “I want to retrace those events, feel the missing part in the story”.

Rafi orders some more arak. “Focus on this principle: in the Middle-East, it is points of view that count, not facts”. Burj Hammoud is now empty, and Rafi’s words snap like stones. “Take the story of the Pobeda, for example. It stopped existing a long time ago. In its place, what is left is the points of view of those who had an interest in Armenians leaving, and of those who, instead, wanted them to stay. And above all this, the Soviet Union”. Rafi’s allusion leaves no room for doubt. “You mean the Lebanese Armenian community was split by the Cold War too?”. Rafi is at his third arak: “It was a fratricide. That war killed hundreds of people right in these alleys. No one likes to admit it, but the trail of blood has reached our days”.

While I am walking away through the deserted alleys of Burj Hammoud, the rosary is told by the splintered walls in front of my eyes. I think back to Rafi’s words, to the unresolved ambiguity of the civil wars, to the warning that seems to come from the bullets thrusted on the walls. “It was not the foreign occupant to open the fire, but the neighbour, never forget that”. Sprayed letters steer these thoughts: “PKK”, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party. The movement born in Turkey in the ‘80s fights for the independence of Turkish Kurdistan, the region that was once the ancient Western Armenia. In the name of anti-Turkish resentment, the children of the Armenian diaspora support the Kurdish cause, even though they accuse the same Kurds of having been accomplices of the Ottoman army during the genocide. The labyrinth of these alleys is a metaphor for the intrigued stories of those living here.

The plane takes off on time from the cement carpet in South Beirut, where Shiite quarters fill every space before making room for the first bits of greenery on the spur of the mountain. From the pile of notes, e-mails and maps that I printed out in a rush before leaving, the answer that Adakessian, the Professor at the Beirut Armenian university, sent me a few hours ago pops out:

Dear Paolo,

I wish you the wisdom you need to discern the fine line and make things better understood. Find the contact of Dr. Demoyan, the director of the Armenian Genocide Research Insitute in Yerevan. This is the Middle East, and the Genocide issue is one of the central ingredients of this intriguing complex.

Regards, A.

Wisdom, insight, complex intrigues. Where am I going, exactly? The night spent organising my journey has left me with doubts, more than answers. And while the vast blue of the sky and the Lebanese sea makes room for leaden landscapes, my mind is suddenly empty and my body finds refuge in deep sleep.