Mostar: the čaršija and the bridge

A divided town, a bridge, a čaršija on each side. Symbols of meeting and congregation which now have to deal with the legacy of the war. The challenge of Mostar between tourism and tradition

If you hear Mostar you think of the Stari Most, the famous Old Bridge, bombed and demolished in 1993 during the war in Bosnia. The town, in fact, takes its name from the word Most which in all Slav languages means bridge. But few know that the bridge in question is situated in the heart of the town and also in the heart of the Mostar čaršija, joining the two historic parts of the town divided by the waters of the Neretva. The čaršija lies on both river banks connected by the famous bridge, bombed and now rebuilt.

The Neretva divides the town into two parts, the Muslim and the Croat. At present in Mostar Muslims and Croats live in two parallel worlds without their Serb fellow citizens who fled during the war. Before the conflict none of the three nationalities had a majority, but now the two identities differ in silence and, with their politicians caring little for the multicultural situation of the town, different curricula are used in the schools, contrasting interpretations of the same facts are taught and they like to think they even speak two different languages: Croatian, laced with Zagreb’s radically purist reforms, and Bosnian, with Turkish and oriental influences often with dialect and archaic forms that are no longer in use. All in the name of keeping their identities separate. This also happens in a small town, which has always been open to the Europe of the Adriatic, to the Herzegovina hinterland and to the rest of the Balkans, both Ottoman and Orthodox.

The Muslim carsija

The bazaar in Mostar is oriental, as is the case anywhere in the Balkans. Vendors remain on the steps of their little shops. They chat to each other, they call each other, they move away. On one of the walls are quoted the verses of a beautiful sevdalinka, a traditional Bosnian musical genre. Here and there is a fez, a blue Ottoman circle against bad luck, and a now globalized souvenir which no longer reflects the authenticity of the area.

Vendors are kind, but laconic, they tend to be impersonal like all other inhabitants of tourist cities, they seem to have lost the drive to trade which was once typical of čaršija workers. It is very hard to get any information on the town as they experience it, on their personal stories. “Here, we are all Muslims, there aren’t any Christians; even if you were to ask everyone in the carsija, you would not find one”. They don’t like talking politics.

“Croatians don’t come over to this side of the bridge, they don’t want to, it’s their own affair” a girl who works as a local tourist guide explains to me. She doesn’t want to dwell on this much either. I ask if this was the case even before the war. Another one cuts me off like this: “ Yes, it has always been only Muslims here.” I ask if before the war he worked in the same shop. His answer is short and vague: “I have always been here, I’m from Mostar.”

The new “old bridge”

Following the čaršija riverbanks, the bridge gradually emerges, white and grand. Flocks of tourists photograph it, others have their picture taken with its impeccable form behind them, others attempt to climb among its steep strips of smooth white marble. It is the symbol of the town and in many ways it is also an image of Bosnia and its dramatic history for the international journalistic scene. Even the čaršija shopkeepers have realized this, so they now sell mainly cards and copies of photographs showing the bridge when it was destroyed in 1993. Dark black and white photos emphasizing the tragic nature of the surroundings of the bridge, blackened, desolate, suspended above the hollow bed of the river, which resembles a terrifying abyss.

The bridge was rebuilt in 2004 thanks to a project of the World Bank, Unesco and Turkey. This re-established communication between the two banks of the river. However it’s as if the broken bridge was never really rebuilt. Even the on the Day of its Inauguration, the Croatian bishop from the other side of town was opposed to the idea of letting children aged under 10, and thus void of relevant memories, walk on it, in a sort of attempt to reconcile and recover the identity of the reconstructed monument. “It would be dangerous for children to walk on the slippery slabs of the new bridge” was the paradoxical excuse adopted.

Italian, a “lingua franca”

Between the entrance to the čaršija and the other side of the bridge, the people of Mostar speak to visitors in Italian. “Prego, prego…” is heard all around. Even the Rom beggars can articulate various sentences in Italian to ask for money. Among the little Muslim shops, small statues of Madonnas can often be spotted. There are in fact a lot of Italian tourists who stop in Mostar, since the town is a destination which is highly advertised by Balkan responsible tourism. However it is mainly due to the vicinity to Medjugorje, a Catholic pilgrimage stopping place which attracts many believers.

Tourism, but also other economic sectors, make Mostar one of the richest towns in Bosnia Herzegovina. Along with tourism, however, come also the disadvantages of integration into a global and commercial market which prefers short term consumerism to local investment and authenticity. Very few are the artisans still operating in the čaršija. War and demographic changes have certainly had a negative impact. Only here and there the odd producer of kilim may be found. “Tourists prefer to buy small souvenirs for a few Euros, replicas of the bridge, or scenes of Mostar”, complains one of the few artisans who in order to sell his kilim has been forced to offer other close-to-kitsch objects, made in China or Turkey.

As well as its heavy postwar inheritance, and the town’s reconciliation, Mostar’s challenge is also that of combining a strongly attractive tourist offer together with the conservation of local tradition and authenticity.

The future of the čaršija

There is a responsible tourism project that intends to help with this, as part of the Seenet II program, with the aim of giving the carsija an aspect of responsible tourism by including it in the context of the Herzegovina region, using the concepts of “open museum” or “eco-museum”.

“Water, light, stone, are the three elements that distinguish Mostar and these will also be the three guidelines that the eco-museum will follow” explains Daria Antenucci, of Oxfam Italy, the Program’s secretariat. It intends to present to the visitors of the čaršija the crafts produced in the shops and the traditional country life of Herzegovina. All enhanced by the creation of an interactive museum, which will act as a theoretical introduction before exploring the entire Mostar territory.

The project has already taken its first steps and, once it is implemented, Mostar will no longer be just a bridge, a postwar landmark or a half-day stop during a visit to Medjugorije , but also the center of an entire region to be discovered.

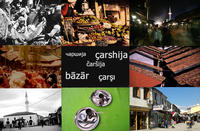

* To make reading easier the ‘bchs’ version of the word (čaršija) is used in the texts on Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia; in those on Albania, the Albanian spelling (çarshija); whereas for the bazaars in Kosovo and Macedonia both wordings are used indifferently.

Tag: Seenet

Mostar: the čaršija and the bridge

A divided town, a bridge, a čaršija on each side. Symbols of meeting and congregation which now have to deal with the legacy of the war. The challenge of Mostar between tourism and tradition

If you hear Mostar you think of the Stari Most, the famous Old Bridge, bombed and demolished in 1993 during the war in Bosnia. The town, in fact, takes its name from the word Most which in all Slav languages means bridge. But few know that the bridge in question is situated in the heart of the town and also in the heart of the Mostar čaršija, joining the two historic parts of the town divided by the waters of the Neretva. The čaršija lies on both river banks connected by the famous bridge, bombed and now rebuilt.

The Neretva divides the town into two parts, the Muslim and the Croat. At present in Mostar Muslims and Croats live in two parallel worlds without their Serb fellow citizens who fled during the war. Before the conflict none of the three nationalities had a majority, but now the two identities differ in silence and, with their politicians caring little for the multicultural situation of the town, different curricula are used in the schools, contrasting interpretations of the same facts are taught and they like to think they even speak two different languages: Croatian, laced with Zagreb’s radically purist reforms, and Bosnian, with Turkish and oriental influences often with dialect and archaic forms that are no longer in use. All in the name of keeping their identities separate. This also happens in a small town, which has always been open to the Europe of the Adriatic, to the Herzegovina hinterland and to the rest of the Balkans, both Ottoman and Orthodox.

The Muslim carsija

The bazaar in Mostar is oriental, as is the case anywhere in the Balkans. Vendors remain on the steps of their little shops. They chat to each other, they call each other, they move away. On one of the walls are quoted the verses of a beautiful sevdalinka, a traditional Bosnian musical genre. Here and there is a fez, a blue Ottoman circle against bad luck, and a now globalized souvenir which no longer reflects the authenticity of the area.

Vendors are kind, but laconic, they tend to be impersonal like all other inhabitants of tourist cities, they seem to have lost the drive to trade which was once typical of čaršija workers. It is very hard to get any information on the town as they experience it, on their personal stories. “Here, we are all Muslims, there aren’t any Christians; even if you were to ask everyone in the carsija, you would not find one”. They don’t like talking politics.

“Croatians don’t come over to this side of the bridge, they don’t want to, it’s their own affair” a girl who works as a local tourist guide explains to me. She doesn’t want to dwell on this much either. I ask if this was the case even before the war. Another one cuts me off like this: “ Yes, it has always been only Muslims here.” I ask if before the war he worked in the same shop. His answer is short and vague: “I have always been here, I’m from Mostar.”

The new “old bridge”

Following the čaršija riverbanks, the bridge gradually emerges, white and grand. Flocks of tourists photograph it, others have their picture taken with its impeccable form behind them, others attempt to climb among its steep strips of smooth white marble. It is the symbol of the town and in many ways it is also an image of Bosnia and its dramatic history for the international journalistic scene. Even the čaršija shopkeepers have realized this, so they now sell mainly cards and copies of photographs showing the bridge when it was destroyed in 1993. Dark black and white photos emphasizing the tragic nature of the surroundings of the bridge, blackened, desolate, suspended above the hollow bed of the river, which resembles a terrifying abyss.

The bridge was rebuilt in 2004 thanks to a project of the World Bank, Unesco and Turkey. This re-established communication between the two banks of the river. However it’s as if the broken bridge was never really rebuilt. Even the on the Day of its Inauguration, the Croatian bishop from the other side of town was opposed to the idea of letting children aged under 10, and thus void of relevant memories, walk on it, in a sort of attempt to reconcile and recover the identity of the reconstructed monument. “It would be dangerous for children to walk on the slippery slabs of the new bridge” was the paradoxical excuse adopted.

Italian, a “lingua franca”

Between the entrance to the čaršija and the other side of the bridge, the people of Mostar speak to visitors in Italian. “Prego, prego…” is heard all around. Even the Rom beggars can articulate various sentences in Italian to ask for money. Among the little Muslim shops, small statues of Madonnas can often be spotted. There are in fact a lot of Italian tourists who stop in Mostar, since the town is a destination which is highly advertised by Balkan responsible tourism. However it is mainly due to the vicinity to Medjugorje, a Catholic pilgrimage stopping place which attracts many believers.

Tourism, but also other economic sectors, make Mostar one of the richest towns in Bosnia Herzegovina. Along with tourism, however, come also the disadvantages of integration into a global and commercial market which prefers short term consumerism to local investment and authenticity. Very few are the artisans still operating in the čaršija. War and demographic changes have certainly had a negative impact. Only here and there the odd producer of kilim may be found. “Tourists prefer to buy small souvenirs for a few Euros, replicas of the bridge, or scenes of Mostar”, complains one of the few artisans who in order to sell his kilim has been forced to offer other close-to-kitsch objects, made in China or Turkey.

As well as its heavy postwar inheritance, and the town’s reconciliation, Mostar’s challenge is also that of combining a strongly attractive tourist offer together with the conservation of local tradition and authenticity.

The future of the čaršija

There is a responsible tourism project that intends to help with this, as part of the Seenet II program, with the aim of giving the carsija an aspect of responsible tourism by including it in the context of the Herzegovina region, using the concepts of “open museum” or “eco-museum”.

“Water, light, stone, are the three elements that distinguish Mostar and these will also be the three guidelines that the eco-museum will follow” explains Daria Antenucci, of Oxfam Italy, the Program’s secretariat. It intends to present to the visitors of the čaršija the crafts produced in the shops and the traditional country life of Herzegovina. All enhanced by the creation of an interactive museum, which will act as a theoretical introduction before exploring the entire Mostar territory.

The project has already taken its first steps and, once it is implemented, Mostar will no longer be just a bridge, a postwar landmark or a half-day stop during a visit to Medjugorije , but also the center of an entire region to be discovered.

* To make reading easier the ‘bchs’ version of the word (čaršija) is used in the texts on Bosnia Herzegovina and Serbia; in those on Albania, the Albanian spelling (çarshija); whereas for the bazaars in Kosovo and Macedonia both wordings are used indifferently.

Tag: Seenet