Tirana Ekspress: destination – future

Since the summer of 2011, the Tirana Ekspress has been the go-to place for young Albanians tired of mainstream musical hegemony in the bllok, the neighbourhood that once housed the communist nomenklatura

A corner of Berlin in Tirana, perhaps much more. Since the summer of 2011, the Tirana Ekspress has gathered young Albanians tired of mainstream musical hegemony in the bllok, the capital’s undisputed night scene. Following the demolition of the original premises (an abandoned warehouse near the old train station), the collective moved down-town, bringing diversity in Rruga George Bush, just a few steps from the Parliament.

Today, as never before, the rhetoric of generational change permeates the debate on Albania, both at home and abroad. The expectations created by the new government, the rekindling of the European perspective, the debated “no” to the United States on chemical weapons, the failure of the only national airline – a year after the centennial, Albania has certainly not solved its problems, but it looks like it is running fast.

The destination, however, is often unknown to the young generations: Albanians’ race to the West is still messy and full – especially as regards youth culture – of the ambiguities and contradictions that typically accompany the transition of former socialist countries.

The dictatorship of the mainstream

The bllok is the socio-architectural expression of the confused, healthy desire that seems to unite young Albanians – bar and music, sounds and sofas mix in this night-life haven, symbolically cut in the fence that housed the inaccessible headquarters of dictator Enver Hoxha and his nomenklatura.

"It used to be impossible to get in, now it is impossible to get out" is the motto of bllok. If fun is guaranteed, artistic quality leaves much to be desired. From the kitsch of ostentatious decorations to new or old tacky music, mainstream rules in most of Tirana as the sole answer to questions that are, however, increasingly diverse.

The choice of diversity

The Tirana Ekspress collective challenges such cultural hegemony to make Albania’s change less rhetorical. Launched in June 2011 from the sides of the old train station, after the demolition of the charming shed that had hosted international performances and artistic events of all kinds for over two years, this group of young volunteers moved to the centre, in the basements that had hosted the legendary Urithi ("the Weasel"), the first club that had opened to the sounds from behind the Iron Curtain in the early nineties.

Strengthened by the centrality of the new headquarters and new members, the Tirana Ekspress maintained the original intent – to be a stage available for the development of a musical and artistic alternative to the commercial logic that unifies the capital’s entertainment scene.

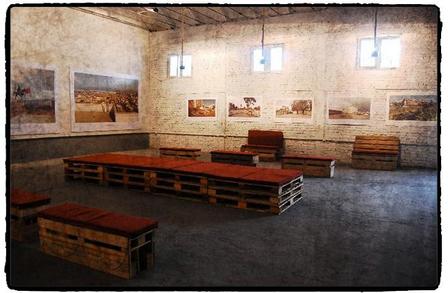

The club, which opened in style on November 8th, 2013, is "different" from the first glance. Guests are welcomed at the entrance by the slate of the old train station (six trains a day left for Durres), at the end of the stairs three small circles appear in dim light: the dining bar, the space for concerts, and the exhibition area.

The wood of the old site was used to cover the walls, and what was left turned into the benches and tables where coffee, tea, and beer are served seven days a week, from 9 am to 11 pm. But this is just for self-financing – the Tirana Ekspress is not a bar, but a project-space led by an artistic direction.

Each day is dedicated to an artistic macro-genre. On Tuesdays, the main room turns into a cinema; on Thursdays, it hosts chamber music ensembles; on Friday evenings, live concerts; every Saturday an exhibition is inaugurated. The uninformed passer-by, crossing the threshold of this unusual station for a coffee or a wi-fi connection, will buy the ticket for a quality artistic journey.

Featured articles

Tirana Ekspress: destination – future

Since the summer of 2011, the Tirana Ekspress has been the go-to place for young Albanians tired of mainstream musical hegemony in the bllok, the neighbourhood that once housed the communist nomenklatura

A corner of Berlin in Tirana, perhaps much more. Since the summer of 2011, the Tirana Ekspress has gathered young Albanians tired of mainstream musical hegemony in the bllok, the capital’s undisputed night scene. Following the demolition of the original premises (an abandoned warehouse near the old train station), the collective moved down-town, bringing diversity in Rruga George Bush, just a few steps from the Parliament.

Today, as never before, the rhetoric of generational change permeates the debate on Albania, both at home and abroad. The expectations created by the new government, the rekindling of the European perspective, the debated “no” to the United States on chemical weapons, the failure of the only national airline – a year after the centennial, Albania has certainly not solved its problems, but it looks like it is running fast.

The destination, however, is often unknown to the young generations: Albanians’ race to the West is still messy and full – especially as regards youth culture – of the ambiguities and contradictions that typically accompany the transition of former socialist countries.

The dictatorship of the mainstream

The bllok is the socio-architectural expression of the confused, healthy desire that seems to unite young Albanians – bar and music, sounds and sofas mix in this night-life haven, symbolically cut in the fence that housed the inaccessible headquarters of dictator Enver Hoxha and his nomenklatura.

"It used to be impossible to get in, now it is impossible to get out" is the motto of bllok. If fun is guaranteed, artistic quality leaves much to be desired. From the kitsch of ostentatious decorations to new or old tacky music, mainstream rules in most of Tirana as the sole answer to questions that are, however, increasingly diverse.

The choice of diversity

The Tirana Ekspress collective challenges such cultural hegemony to make Albania’s change less rhetorical. Launched in June 2011 from the sides of the old train station, after the demolition of the charming shed that had hosted international performances and artistic events of all kinds for over two years, this group of young volunteers moved to the centre, in the basements that had hosted the legendary Urithi ("the Weasel"), the first club that had opened to the sounds from behind the Iron Curtain in the early nineties.

Strengthened by the centrality of the new headquarters and new members, the Tirana Ekspress maintained the original intent – to be a stage available for the development of a musical and artistic alternative to the commercial logic that unifies the capital’s entertainment scene.

The club, which opened in style on November 8th, 2013, is "different" from the first glance. Guests are welcomed at the entrance by the slate of the old train station (six trains a day left for Durres), at the end of the stairs three small circles appear in dim light: the dining bar, the space for concerts, and the exhibition area.

The wood of the old site was used to cover the walls, and what was left turned into the benches and tables where coffee, tea, and beer are served seven days a week, from 9 am to 11 pm. But this is just for self-financing – the Tirana Ekspress is not a bar, but a project-space led by an artistic direction.

Each day is dedicated to an artistic macro-genre. On Tuesdays, the main room turns into a cinema; on Thursdays, it hosts chamber music ensembles; on Friday evenings, live concerts; every Saturday an exhibition is inaugurated. The uninformed passer-by, crossing the threshold of this unusual station for a coffee or a wi-fi connection, will buy the ticket for a quality artistic journey.