Politics and hate speech in the Turkish media

During the elections that have just ended in Türkiye, the candidates used a discriminating and aggressive discourse. We talked about it with Yasemin Korkmaz, coordinator of the hate speech monitoring campaign in Türkiye at the Hrant Dink Foundation

Politica-e-discorsi-d-odio-nei-media-turchi

Headquarters of the Hrant Dink Foundation in Istanbul © Hrant Dink Foundation

During the last elections in Türkiye, both presidential candidates used discriminating and aggressive rhetoric. In particular, especially between the first and second rounds, marginalised categories such as the Syrian refugee community found themselves exposed to the verbal crossfire of the two sides: repatriating all the people who fled the war in Syria seemed at one point the top priority for the country. Similarly, during the various electoral rallies, political figures such as the current Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu did not hesitate to bring up the bogeyman of LGBT+ rights as a looming threat to the integrity of the country.

We spoke to Yasemin Korkmaz, Hate Speech Monitoring Campaign Coordinator in Türkiye at the Hrant Dink Foundation (based in Istanbul) to better understand the extent and consequences of this phenomenon, which appeared to be very pervasive during the last electoral appointment in the country. In fact, the foundation has been involved in drawing up reports and analyses on the presence of hate speech and discriminatory speech in the media and in political debate for more than a decade, as well as carrying out campaigns to stem the problem and raise awareness of these issues in the Turkish society.

Why do you think it is necessary to deal with the phenomenon of hate speech?

Our association was founded after the assassination of Armenian journalist Hrant Dink, and his case is closely linked to the spread and practice of hate speech. Before his death, his figure was regularly targeted by Turkish communication channels and as a final result of such an attack there was precisely a hate crime. Obviously not all hate speech leads to a crime but, from our point of view, it is a first level in which discrimination within society is created and exacerbated.

Therefore, since 2009 we have decided to monitor hate speech in the public debate in our country, analysing in particular both local and national media. We identify the various categories of hate speech but above all the groups that become its targets from time to time. On the one hand we are interested in drawing attention to the responsibility of journalists, who are required to be aware of the tones in which they express themselves, on the other hand we want to make the issue known to the public opinion as much as possible. In this sense, the quantitative aspect of our research is very important: very often hate speech can appear as a vague phenomenon and all in all not so relevant, but if we are confronted with its pervasiveness with objective data are more inclined to reflect on it and to consider it as a question to be addressed.

What did you observe during the last electoral round?

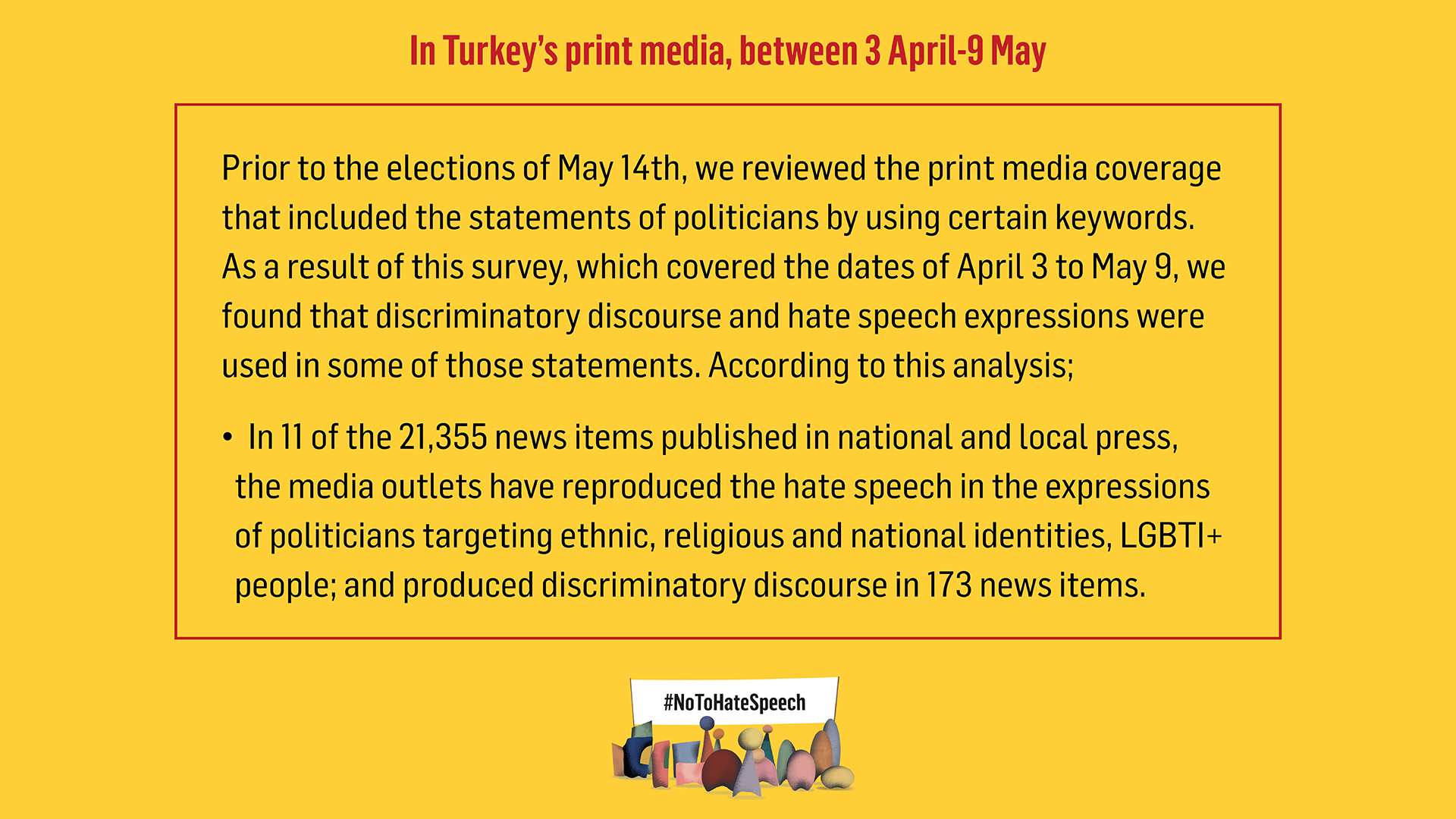

During the elections and the electoral campaign in Türkiye, we noticed how hate speech and discriminatory rhetoric were used by both political parties and very often targeted the category of refugees and LGBT+ people. The positive fact is that there has been a discrepancy in quantitative terms between the presence of hate speech in the statements of political leaders, on the one hand, and in newspaper articles and reports, on the other hand: as I mentioned, I believe a greater awareness of the problem on the part of media professionals has developed over time and, therefore, very often hate speech coming from the political class is avoided in journalistic reports, even if only in the form of quotation.

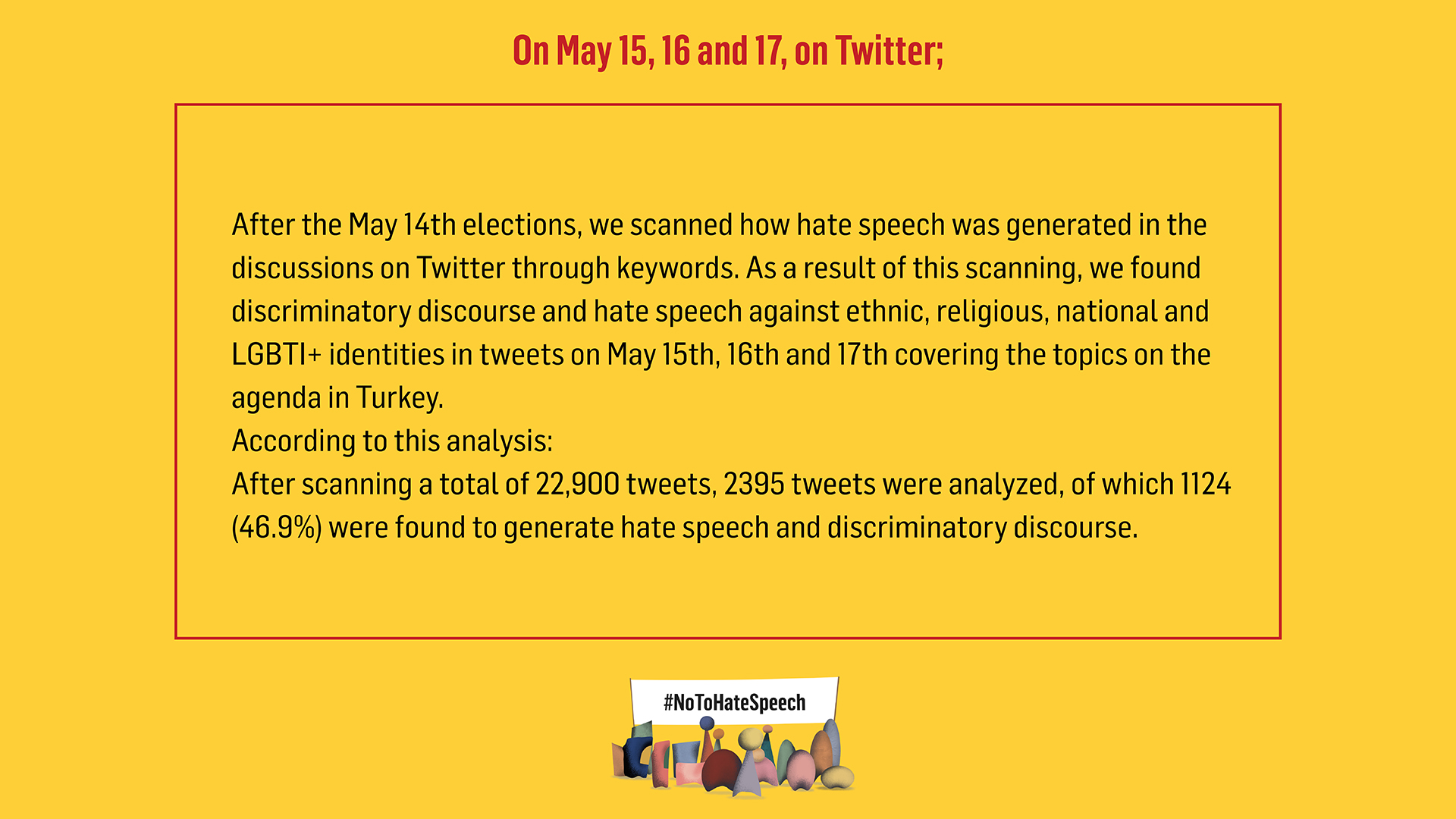

That said, analysing instead the debate that has developed on social media and specifically on Twitter, we have noticed some trends: the term "Alevi", for which we expected a high diffusion since one of the two candidates had used his own Alevi origins as an electoral claim, was very often associated in a way most of the time indistinguishable from the term "Armenian" and perhaps used as an insult. For the category of migrants of mainly Syrian or Afghan origin, one of the interesting elements is how public discourse only focuses on men: the "refugees", the "migrants", in short, are almost always men who arrive in our country and in one way or another pose a threat. Finally, a term widely used as an insult, applied both to refugees and LGBT+ people, is "pervert": here too, in various instances, migrants and people with non-traditional sexual orientation and/or gender identity are seen as a threat to the traditional structure of the family or as a problem of a moral nature for the whole social body.

Is it a problem that has to do with the mindset of the political class?

All political forces, in one way or another, have used discriminatory discourses. Unfortunately, this really is a very common practice and if it is true that there are certain political figures who insist more than others on such a communication strategy, I do not think the problem is simply individual. Surely it is also the reflection of a more structural issue that concerns the whole of society and for which, therefore, an overall change is necessary.

I would also add that the spread of hate speech or discriminatory speech is not limited to the electoral period, but remains more or less constant throughout the year. This is especially true for certain categories, such as Syrians, Armenians, Christians, and Jews who are virtually always the target of aggressive discourse in the media (the intensity of which is perhaps also influenced by changes in the country’s international relations). The solution for us therefore remains to work on general awareness, learn to recognise the discrimination inherent in the use of certain types of language, and offer tools to achieve this goal to an ever-increasing number of people.

| This publication was produced within the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR), co-funded by the European Commission. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso Transeuropa and its partners and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. |