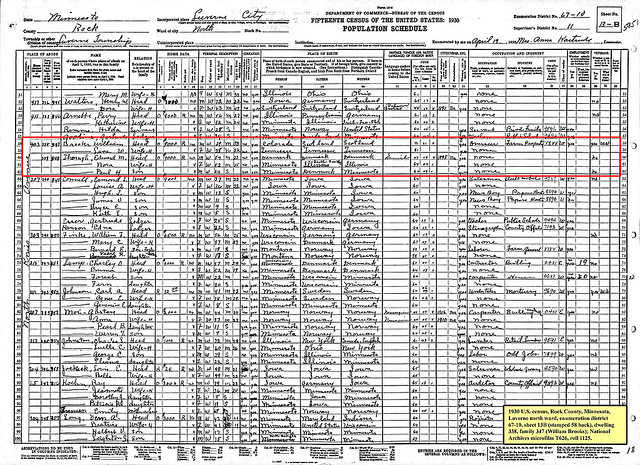

Census - Birdie Holsclaw/flickr

In Macedonia, the census planned for October has officially been cancelled. The fiasco came as a result of increasing tensions between the two major partners in the government, the VMRO led by Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski and the DUI of Ali Ahmeti. Assessing the number of citizens (and the weight of the different ethnic communities) in Macedonia is a sensitive and highly politicized issue

Since Macedonia’s census was stopped a week ago, the country’s political opposition has continually offered sharp criticisms. The major opposition party in the Macedonian parliament, the Social Democratic Union (SDSM), called on government officials to personally return the estimated 14 million euros wasted on the failed operation.

The census, which started on 1 October, was interrupted four days before its scheduled completion date, when the State Census Commission (SCC) resigned on 11 October. The SCC’s brief press release asked all surveyors to stop; according to the announcement, the census had been suspended because different field interpretations of the surveying methodology could not guarantee reliable data.

The government tried to downplay the matter, while the opposition party SDSM insisted on assigning political responsibility for the fiasco and the resulting financial loss. The opposition social democratic party suggested each government official should pay 16,000 euros to restore the 14 million euros that had been squandered on the unsuccessful project.

The issue is essentially ethno-political: the Albanian political faction insisted on a census methodology that counted the many Albanian emigrants, some of whom may not have returned to the country for years. However, standard Eurostat methodology does not count a person living abroad for more than 12 months.

In the field, the census apparently turned into havoc. Albanians tried to maximise their numbers, Macedonians responded, and soon the process stopped.

Problems appeared even before the operation began. Only hours before the scheduled start of the census, many did not know if it would actually commence. The lack of clear political consensus, which was ultimately the major factor in the failure, produced an organisational nightmare. When the census was officially aborted, the process had barely started in entire regions in the country.

Besides wasting resources, the political significance of the fiasco signal an early rupture in the old-new government coalition between VMRO DPMNE of Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski, and the Democratic Union for Integration (DUI) of Ali Ahmeti.

Tensions in the Gruevski-Ahmeti coalition caused the snap national vote on 5 June. Immediately before the election, their partnership had seemed to be disintegrating. Prime Minister Gruevski went to the polls hoping to crush his arch-rival Branko Crvenkovski of SDSM, extend his term in office, and also produce a new government coalition. This indeed happened but to the detriment of VMRO. Despite losing parliamentary seats, DUI remained strong, and brought heavier influence into the new government. Now Ahmeti has a stronger negotiating position and wants more power. The failed census clearly indicates that the partners in government did not have a specific agreement on how to do the population count. They agreed to proceed, but apparently stumbled over details. Whatever the justification, a political decision suspended the census. Had there been political backing, organisational issues would have been fixed.

This first conflict does not seem to have had lasting effect on the government coalition, which recently took office. Both DUI and VMRO first reacted by minimizing the issue. Gruevski has made no statements on the issue, whereas Ahmeti said he supported the resignation of the SCC. Other DUI government members also dismissed the matter and said a postponement of the census was the least of the country’s problem. The government proposed a bill to parliament to verify the termination of the operation, which passed by a small margin. After a fiery debate, the opposition boycotted the vote.

In the week since the census failed, VMRO has argued that they performed a great patriotic act by stopping the census. In refusing to do the count as allegedly the Albanians wanted, they say they protected the national interest of the ethnic Macedonians. They accused SDSM and Crvenkovski of allowing an overcount of the Albanians during the last census, which took place in 2002, shortly after the end of the conflict. They claim that in reality, the Albanian community is less than 25% as the last census showed. Some analysts refuted this argument by referring to data from previous censuses.

After the 2001 ethnic conflict, the Ohrid Framework Agreement that ended the war had tied collective rights for ethnic communities to their share in the total population, with major entitlements linked to a threshold of 20%. This further exacerbates the census tension. The population count has, however, always been a highly politicised issue in the country. After the last census in 2002, results were finally released only after months of tense speculations. The previous censuses conducted in the 1990s also had problems. The Albanians boycotted the census conducted in 1991. The next census apparently had better results in 1994, even though some claim that it suffered from the ethno-political flaws.

Social scientists want a census that would produce new data on dimensions of social reality in a country chronically lacking good data about many things. Apart from social scientists, most others are only interested in how many belong to their ethnic group.