Bosnia and Herzegovina, the “broken pipes” of history

In several cities of Bosnia and Herzegovina, from May 28th to June 2nd, an important history festival was held which brought together about 100 historians from the region. This year, however, the History Fest has become a case of ethno-political tension

Bosnia-and-Herzegovina-the-broken-pipes-of-history

An unsigned letter and a mysterious broken pipe triggered the new history war in the former Yugoslav region. Almost three decades have passed since the beginning of the crisis that led to the dissolution of Yugoslavia, and in recent years there have been numerous initiatives to circulate ideas and compare different historiographical approaches.

Conferences, joint publications, researcher and student mobility are growing, but the forces that dominate the political framework do not accept the questioning of their own myths and canonical narratives on the ’20th century and in particular on the 1990s. This is supported by media pressure and a climate of general conformity in cultural and educational institutions.

In this context, Bosnia and Herzegovina stands out negatively, as shown by the revisionist discourse of Bosniak nationalism – see the rehabilitation in Sarajevo of Mustafa Busuladžić, a pro-ustaša and pro-fascist intellectual – and Serbian nationalism – with the repeated revisionist attempts by the institutions of Republika Srpska on the facts of Srebrenica.

The latest example of this tension is the case of the History Fest, an annual history festival now in its third edition, held between May 28th and June 2nd in different cities of the country (Sarajevo, Mostar, Banja Luka, and Konjic). The promoter of the History Fest is a non-governmental body from Sarajevo, the Association for a Modern History (UHMIS), chaired by Husnija Kamberović, one of the most important contemporary historians in the region.

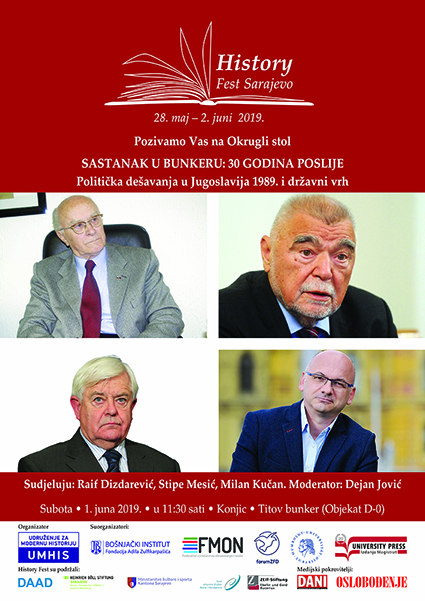

This year, the History Fest brought together about a hundred historians, intellectuals, young researchers, and direct witnesses from the post-Yugoslav and international sphere. The central theme of the festival was the fall of communism and the comparison between the different 1989s – the Yugoslav and the European one. There were several notable guests, including former Slovenian president Milan Kučan and Croatian president Stipe Mesić, Serbian historical and politicians Ljubinka Trgočević and Latinka Perović, former Bosnian members of the Yugoslav presidency Raif Dizdarević and Bogić Bogičević.

On May 31st, while travelling from Sarajevo to the National Theatre of Banja Luka where a festival event was to be held, Husnija Kamberović received a sudden phone call, warning him that at the theatre a "pipe" had broken out that made it impossible to hold the event. In a hurry, the organisers found an alternative, a modest room in a city centre hotel. Yet the suspicion spread that, rather than an accident, there had been political pressure on the National Theatre, owned by the Republika Srpska government, to obstruct the festival. The news became public, but the theatre – with a dense agenda of events that did not undergo any other changes in those days – issued no official communication. At the same time, a letter that increased suspicions began to circulate on the media and social networks.

Manipulations of history

The letter is laconically signed "History Study Programme", with a heading of the faculty of Philosophy of the University of Banja Luka, but without names and surnames. This is a protest appeal against "the manipulation of history at the National Theatre of the Republika Srpska". The document attacks the organisers of the History Fest, who allegedly "avoided involving authors from the Republika Srpska" and instead invited some Serbian intellectuals – Latinka Perović, Sonja Biserko, Milivoje Beslin, Dubravka Stojanović – defined as "full-blown promoters of the Bosniak national ideology". The participation of politicians protagonists of the Yugoslav crisis of the 1980s and 1990s is also criticised, as no "relevant representative of Serbian politics of those years" was allegedly included.

The letter then cites research on historical events crucial to the Serbian people that would have been presented at the festival, including Jasenovac by well-known Croatian historian Ivo Goldstein, devoted to the Ustasha extermination camp for Serbs, Jews, Roma, and partisans. With some allusions, the letter seems to lament the fact that research was being carried out on the Serbian people written by non-Serbs. In conclusion, the document defines the History Fest as an "anti-Serbian provocation" and invites the institutions of Republika Srpska to take action

Although the festival has ended without incidents, with an increase in participants and public, this rift can leave serious consequences in the country’s scientific and intellectual environment. It is surprising how the matter was raised, with a semi-anonymous document that seems to instigate segregation and self-censorship, with oppressive and almost intimidating ad personas. It is an approach that eliminates any possibility of dialogue, and suffocates the invocation – legitimate, and perhaps necessary, after almost thirty years – to explore certain gray areas on the conflicts of the nineties, which the many black-and-white interpretations continue to remove.

Other worrying elements seem to confirm the presence of a climate that is not exactly favourable to freedom of expression in Banja Luka. All the media outlets in the Republika Srpska, including opposition ones – with the exception of the independent Buka – have been completely silent on the matter. Almost none of the city’s intellectuals wrote and took a stand in solidarity with the History Fest, with the usual exception of Srđan Puhalo and Dragan Bursać. "I think they wanted the hologram of Slobodan Milošević, or his court jester Vojislav Šešelj, to show up that day", said Puhalo. The author himself recalls that in 2017 the University of Banja Luka hosted the screening of an apologetic film on Radovan Karadžić, yet no one at the time spoke of politicisation of history. It should be acknowledged that even in Sarajevo and in the rest of Bosnia and Herzegovina the case seems to have received little attention, partly due to resignation and addiction to the climate of cultural segregation, partly because the themes of everyday life take over, partly because "memory excess" syndrome pushes individuals to retreat into private memory and accept existing myths, rather than seeking comparison and innovation in historiographical approaches.

A rational dialogue

Contacted by OBC Transeuropa, the director of History Fest Husnija Kamberović tries to put things in perspective. "Judging by the reactions, the festival went very well, apart from the Banja Luka affair that we should not live like a tragedy". However, he responds drastically to the accusations, stressing that "the concept of the Festival is not based on the presence of certain national historiographic representations, as the authors of that letter seem to think, but on the participation of historians who reflect critically on the past and are ready for a rational dialogue".

The accusation of never having invited any historian from Republika Srpska is, claims Kamberović, "totally false: both this year and in the past years we invited some historians from Banja Luka, certainly not as representatives of Republika Srpska as such, but as historians who present their own work. We also presented with them publications from the Faculty of Philosophy itself [from which the letter comes, ed.]". Kamberović lists us in detail the many joint events that have taken place in recent years with Banja Luka’s colleagues, as if to claim a spontaneous and constant normality of collaboration, not very visible at the time, very noisy now that it is missing.

On the risk of ethnic segregation of historical research, Kamberović explains: "The letter claims that some participants will present work that deals directly with the history of the Serbian people in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is not entirely clear what is meant by this, but it seems to imply that the history of the Serbian people can only be told by Serbian historians, and here we disagree, because we want to build a critical approach to historical problems, not to close ourselves in our own national spaces. Relegating history into national boundaries does not lead to scientific historiography, but to affirmation of nationalism in historiography. Here we disagree".

As for the non-invitation of representatives of Serbian politics in the 1980s and 1990s, Kamberović reveals an unprecedented detail. "Actually I tried to invite all the members of the last Yugoslav collective presidency still alive. I spoke at length with everyone, also with Borisav Jović [the Serbian member of the Yugoslav collective presidency in 1990-91; at the time right arm of Slobodan Milošević, ed.], we agreed with him he would participate. I wanted an open discussion and maybe new elements, but then Borisav Jović decided not to participate, and I don’t want to reveal the reasons, he will if he wants to".

In conclusion, we ask Kamberović if there will be consequences for the future of the festival. "My position has always been, and will remain in the future, that the History Fest cannot and must not be politically exploited. The fact that the authors of the letter attribute to us their own politicisation of history is a consolidated tactic. "There was no reaction from the Banja Luka academic community to this scandalous letter, and for me this is a cause for disappointment. But no one will stop us in our intention to defend the dignity of historical science, to cultivate the idea of dialogue, no one will make us consent to the ethnicisation and politicisation of history".

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Bosnia and Herzegovina, the “broken pipes” of history

In several cities of Bosnia and Herzegovina, from May 28th to June 2nd, an important history festival was held which brought together about 100 historians from the region. This year, however, the History Fest has become a case of ethno-political tension

Bosnia-and-Herzegovina-the-broken-pipes-of-history

An unsigned letter and a mysterious broken pipe triggered the new history war in the former Yugoslav region. Almost three decades have passed since the beginning of the crisis that led to the dissolution of Yugoslavia, and in recent years there have been numerous initiatives to circulate ideas and compare different historiographical approaches.

Conferences, joint publications, researcher and student mobility are growing, but the forces that dominate the political framework do not accept the questioning of their own myths and canonical narratives on the ’20th century and in particular on the 1990s. This is supported by media pressure and a climate of general conformity in cultural and educational institutions.

In this context, Bosnia and Herzegovina stands out negatively, as shown by the revisionist discourse of Bosniak nationalism – see the rehabilitation in Sarajevo of Mustafa Busuladžić, a pro-ustaša and pro-fascist intellectual – and Serbian nationalism – with the repeated revisionist attempts by the institutions of Republika Srpska on the facts of Srebrenica.

The latest example of this tension is the case of the History Fest, an annual history festival now in its third edition, held between May 28th and June 2nd in different cities of the country (Sarajevo, Mostar, Banja Luka, and Konjic). The promoter of the History Fest is a non-governmental body from Sarajevo, the Association for a Modern History (UHMIS), chaired by Husnija Kamberović, one of the most important contemporary historians in the region.

This year, the History Fest brought together about a hundred historians, intellectuals, young researchers, and direct witnesses from the post-Yugoslav and international sphere. The central theme of the festival was the fall of communism and the comparison between the different 1989s – the Yugoslav and the European one. There were several notable guests, including former Slovenian president Milan Kučan and Croatian president Stipe Mesić, Serbian historical and politicians Ljubinka Trgočević and Latinka Perović, former Bosnian members of the Yugoslav presidency Raif Dizdarević and Bogić Bogičević.

On May 31st, while travelling from Sarajevo to the National Theatre of Banja Luka where a festival event was to be held, Husnija Kamberović received a sudden phone call, warning him that at the theatre a "pipe" had broken out that made it impossible to hold the event. In a hurry, the organisers found an alternative, a modest room in a city centre hotel. Yet the suspicion spread that, rather than an accident, there had been political pressure on the National Theatre, owned by the Republika Srpska government, to obstruct the festival. The news became public, but the theatre – with a dense agenda of events that did not undergo any other changes in those days – issued no official communication. At the same time, a letter that increased suspicions began to circulate on the media and social networks.

Manipulations of history

The letter is laconically signed "History Study Programme", with a heading of the faculty of Philosophy of the University of Banja Luka, but without names and surnames. This is a protest appeal against "the manipulation of history at the National Theatre of the Republika Srpska". The document attacks the organisers of the History Fest, who allegedly "avoided involving authors from the Republika Srpska" and instead invited some Serbian intellectuals – Latinka Perović, Sonja Biserko, Milivoje Beslin, Dubravka Stojanović – defined as "full-blown promoters of the Bosniak national ideology". The participation of politicians protagonists of the Yugoslav crisis of the 1980s and 1990s is also criticised, as no "relevant representative of Serbian politics of those years" was allegedly included.

The letter then cites research on historical events crucial to the Serbian people that would have been presented at the festival, including Jasenovac by well-known Croatian historian Ivo Goldstein, devoted to the Ustasha extermination camp for Serbs, Jews, Roma, and partisans. With some allusions, the letter seems to lament the fact that research was being carried out on the Serbian people written by non-Serbs. In conclusion, the document defines the History Fest as an "anti-Serbian provocation" and invites the institutions of Republika Srpska to take action

Although the festival has ended without incidents, with an increase in participants and public, this rift can leave serious consequences in the country’s scientific and intellectual environment. It is surprising how the matter was raised, with a semi-anonymous document that seems to instigate segregation and self-censorship, with oppressive and almost intimidating ad personas. It is an approach that eliminates any possibility of dialogue, and suffocates the invocation – legitimate, and perhaps necessary, after almost thirty years – to explore certain gray areas on the conflicts of the nineties, which the many black-and-white interpretations continue to remove.

Other worrying elements seem to confirm the presence of a climate that is not exactly favourable to freedom of expression in Banja Luka. All the media outlets in the Republika Srpska, including opposition ones – with the exception of the independent Buka – have been completely silent on the matter. Almost none of the city’s intellectuals wrote and took a stand in solidarity with the History Fest, with the usual exception of Srđan Puhalo and Dragan Bursać. "I think they wanted the hologram of Slobodan Milošević, or his court jester Vojislav Šešelj, to show up that day", said Puhalo. The author himself recalls that in 2017 the University of Banja Luka hosted the screening of an apologetic film on Radovan Karadžić, yet no one at the time spoke of politicisation of history. It should be acknowledged that even in Sarajevo and in the rest of Bosnia and Herzegovina the case seems to have received little attention, partly due to resignation and addiction to the climate of cultural segregation, partly because the themes of everyday life take over, partly because "memory excess" syndrome pushes individuals to retreat into private memory and accept existing myths, rather than seeking comparison and innovation in historiographical approaches.

A rational dialogue

Contacted by OBC Transeuropa, the director of History Fest Husnija Kamberović tries to put things in perspective. "Judging by the reactions, the festival went very well, apart from the Banja Luka affair that we should not live like a tragedy". However, he responds drastically to the accusations, stressing that "the concept of the Festival is not based on the presence of certain national historiographic representations, as the authors of that letter seem to think, but on the participation of historians who reflect critically on the past and are ready for a rational dialogue".

The accusation of never having invited any historian from Republika Srpska is, claims Kamberović, "totally false: both this year and in the past years we invited some historians from Banja Luka, certainly not as representatives of Republika Srpska as such, but as historians who present their own work. We also presented with them publications from the Faculty of Philosophy itself [from which the letter comes, ed.]". Kamberović lists us in detail the many joint events that have taken place in recent years with Banja Luka’s colleagues, as if to claim a spontaneous and constant normality of collaboration, not very visible at the time, very noisy now that it is missing.

On the risk of ethnic segregation of historical research, Kamberović explains: "The letter claims that some participants will present work that deals directly with the history of the Serbian people in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is not entirely clear what is meant by this, but it seems to imply that the history of the Serbian people can only be told by Serbian historians, and here we disagree, because we want to build a critical approach to historical problems, not to close ourselves in our own national spaces. Relegating history into national boundaries does not lead to scientific historiography, but to affirmation of nationalism in historiography. Here we disagree".

As for the non-invitation of representatives of Serbian politics in the 1980s and 1990s, Kamberović reveals an unprecedented detail. "Actually I tried to invite all the members of the last Yugoslav collective presidency still alive. I spoke at length with everyone, also with Borisav Jović [the Serbian member of the Yugoslav collective presidency in 1990-91; at the time right arm of Slobodan Milošević, ed.], we agreed with him he would participate. I wanted an open discussion and maybe new elements, but then Borisav Jović decided not to participate, and I don’t want to reveal the reasons, he will if he wants to".

In conclusion, we ask Kamberović if there will be consequences for the future of the festival. "My position has always been, and will remain in the future, that the History Fest cannot and must not be politically exploited. The fact that the authors of the letter attribute to us their own politicisation of history is a consolidated tactic. "There was no reaction from the Banja Luka academic community to this scandalous letter, and for me this is a cause for disappointment. But no one will stop us in our intention to defend the dignity of historical science, to cultivate the idea of dialogue, no one will make us consent to the ethnicisation and politicisation of history".