Winds of change in the Adriatic for offshore wind energy

Obtaining renewable energy from the wind by installing turbines in the open sea will be increasingly necessary, but so is respecting biodiversity. In the Adriatic, this challenge is still open: the Beyond project was born to win it, starting from Italy and Croatia

Winds-of-change-in-the-Adriatic-for-offshore-wind-energy

Offshore wind turbines in the Netherlands - © fokke baarssen/Shutterstock

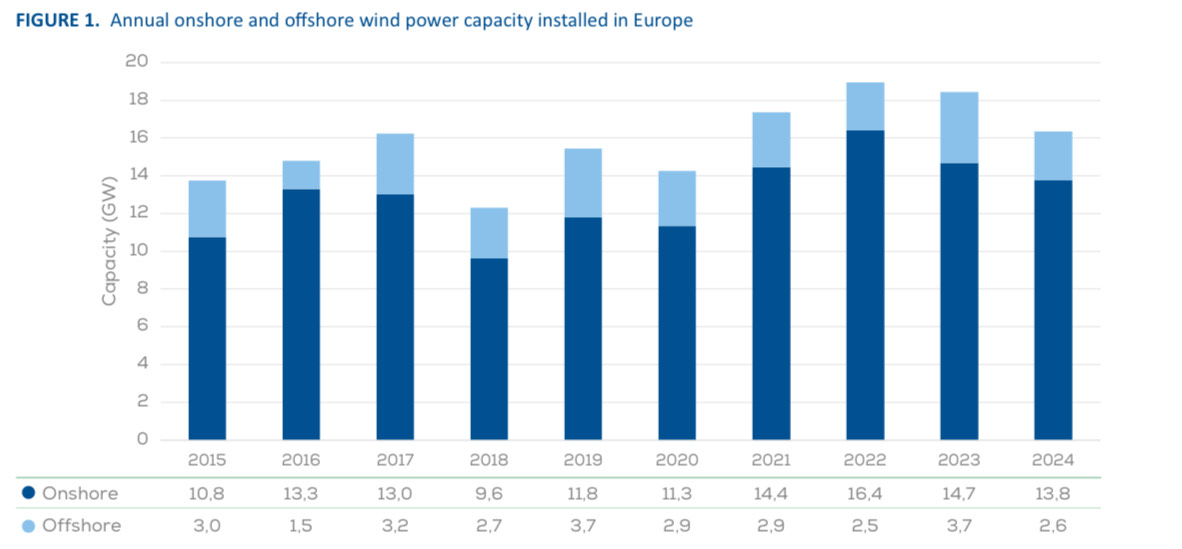

Between 2015 and 2021, offshore wind in Europe recorded + 326% of its nominal value. Only in 2024, according to WindEurope , there was an increase in production capacity equal to 2.6 GW and there will have to be more, at least until 2030, if the EU remains faithful to its strategy for the offshore production of renewable energy which promises to "install on average almost 12 GW/year".

Offshore wind will therefore not remain a niche sector, in fact it will most likely be an increasingly visible presence both in the energy baskets of the member states and in our landscapes.

This is also confirmed by Paolo Della Ventura, an expert in wind energy who has been reporting on its developments on the Via col Vento website for years and who, as a member of the board of the Italian Climate Network , underlines its importance also from a climate point of view. It considers it a fundamental renewable to try to respect the energy commitments made in 2015 with the Paris Agreement to contain the increase in global temperature.

Figures

"The climate crisis is increasingly faster and more ferocious and must be addressed with every possible means, without inventing anything new. The latest report by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) shows us the way: focus on solar and wind – explains Della Ventura – among these, the technology with the greatest yield in terms of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and costs is precisely that of offshore wind. In the coming years it will be increasingly widespread and, probably, also more efficient, especially seeing the progress made in China".

The math on what has been achieved so far only in Europe clearly shows that offshore has lower costs, compared to fossil fuels, but also compared to onshore wind.

“In onshore plants, each individual turbine produces an average of 5 MW, so to create a 40 MW park you need at least 8. With offshore, you have 15-18 MW per single turbine, so for a park with equivalent production you only need 3 – explains Della Ventura – they are blades with an average height of 220 meters and are able to optimize the wind capacity present at sea, more constant and powerful. In the future, we aim to create individual turbines of over 20 MW”.

Respect for biodiversity is not optional

If these figures suggest that offshore wind power will have a smooth path, others suggest caution in implementing it everywhere. For example, those relating to the risks that its plants may pose for marine and terrestrial biodiversity.

According to an English study published in 2024, in fact, in the construction phase, their impact is defined as "predominantly negative (52%)" especially for marine species such as sole, cod, plaice and for birds such as guillemot, northern fulmar and tufted duck.

The operational phase is less concerning, in which the effects on biodiversity can be both negative (32%) and positive (34%). Much depends on the species, the type of plant and, above all, the geographical and environmental situation in which a plant has been installed.

To let offshore wind power advance (and the European green transition) but let fish and birds live in their natural habitat, it is therefore necessary to analyse each individual context in detail, taking more time to carry out environmental assessments.

The same study says so, underlining that "in general, over 86% of the possible impacts of offshore wind power on biodiversity remains unknown". This is confirmed by Gianluca Sarà, a marine ecologist at the University of Palermo who has personally collaborated with institutions to estimate the consequences that a particular offshore wind project could have on marine flora and fauna.

“Each assessment should be divided into three, one for each component of the plant. The part that attaches to the sediments on the seabed is the one that causes the most damage, especially near the coast, because up to about 300 meters away there is greater biodiversity and many communities also used by fishing live there. Further out, the negative effects can be more limited – says Sarà – this is true in general but, in the Adriatic, it must be taken into account that the seabed is mainly composed of terrigenous mud and is home to delicate and protected species.

A pre-installation analysis of offshore wind should therefore include a particularly careful assessment of the benthic communities present, to avoid damaging those of priority importance for conservation purposes”.

There are not always negative effects and they are not always long-lasting, but in any case with the attachment of the plant to the seabed "the three-dimensional structure of the seabed inevitably changes and most of the species that live there, not having the possibility of moving, are forced to adapt to it".

Thinking about the other two components of the plants, the one that appears on the surface and the one that intervenes on the underlying water column, Sarà says he is less worried because "species capable of moving easily live there and the consequences on their conservation are less negative".

After seeing with his own eyes what the studies carried out in view of the construction of offshore wind plants are like, the ecologist remains convinced that, even if foreseen by the protocol, the protection of biodiversity is not yet a real priority both for those who invest in an offshore wind project and for those who evaluate it from the outside.

“There are still approval procedures strongly aimed at maximizing energy performance, in a serious cost-benefit study, biodiversity should appear as a fundamental component to be evaluated, not an accessory – he explains – It would add complexity but green transition and environmental protection must go hand in hand. And the ways to make this happen exist”.

The Adriatic faces wind power with Beyond

Not in the Adriatic, where offshore wind power has yet to take off, but examples of plants built taking into account pre-existing biodiversity can be found in several already operating in Northern Europe.

In the Netherlands, the Fryslan wind farm, which powers 500,000 homes north of Amsterdam, uses artificial intelligence to monitor and avoid harming seabirds such as the tern, for example, and was designed from the start with the welfare of wildlife in mind.

The same goes for the Hornsea 3 offshore wind farm in England, together with which a series of artificial nesting structures for seabirds were built as ecological compensation measures.

As for the impacts on underwater biodiversity, an example to draw inspiration from could be the artificial reefs to stimulate marine life installed near the Hollandse Kust offshore wind farm in the Netherlands, on the North Sea. Or the Kriegers Flak plant managed jointly by the Swedish state electricity company Vattenfall and the University of Aarhus in Denmark, planned from the beginning so that an experimental seafood farm could be built under the turbines.

The inclusion in the widespread network of Natura 2000 ecological sites obtained in March 2025 by Sweden for its 2.5 GW Mareld floating wind farm is yet another signal for those who are designing, evaluating or building those that will be built in the Adriatic: renewable energy plants can and must be allies of biodiversity.

To reiterate this and encourage other member countries to implement projects like those mentioned, in spring 2024 the European Union launched a 1.76 million euro interregional project (80% financed by the European Regional Development Fund) in the Mediterranean area to identify an inclusive offshore wind model that is attentive to biodiversity and local communities, as well as the number of Watts produced.

It is called Beyond and focuses on four “pilot” regions identified between Croatia and Italy. It aims to design and test new offshore wind models that produce renewable energy but do not damage biodiversity, neither in the short nor the long term. It is true that offshore wind is only now gaining ground in the Adriatic but, even more so, it is better to start off on the right foot.

This article is published in the context of the project "Cohesion4Climate" co-funded by the European Union. The EU is in no way responsible for the information or views expressed within the framework of the project; the sole responsibility for the content lies with OBCT.

Tag: Cohesion for Climate

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Winds of change in the Adriatic for offshore wind energy

Obtaining renewable energy from the wind by installing turbines in the open sea will be increasingly necessary, but so is respecting biodiversity. In the Adriatic, this challenge is still open: the Beyond project was born to win it, starting from Italy and Croatia

Winds-of-change-in-the-Adriatic-for-offshore-wind-energy

Offshore wind turbines in the Netherlands - © fokke baarssen/Shutterstock

Between 2015 and 2021, offshore wind in Europe recorded + 326% of its nominal value. Only in 2024, according to WindEurope , there was an increase in production capacity equal to 2.6 GW and there will have to be more, at least until 2030, if the EU remains faithful to its strategy for the offshore production of renewable energy which promises to "install on average almost 12 GW/year".

Offshore wind will therefore not remain a niche sector, in fact it will most likely be an increasingly visible presence both in the energy baskets of the member states and in our landscapes.

This is also confirmed by Paolo Della Ventura, an expert in wind energy who has been reporting on its developments on the Via col Vento website for years and who, as a member of the board of the Italian Climate Network , underlines its importance also from a climate point of view. It considers it a fundamental renewable to try to respect the energy commitments made in 2015 with the Paris Agreement to contain the increase in global temperature.

Figures

"The climate crisis is increasingly faster and more ferocious and must be addressed with every possible means, without inventing anything new. The latest report by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) shows us the way: focus on solar and wind – explains Della Ventura – among these, the technology with the greatest yield in terms of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and costs is precisely that of offshore wind. In the coming years it will be increasingly widespread and, probably, also more efficient, especially seeing the progress made in China".

The math on what has been achieved so far only in Europe clearly shows that offshore has lower costs, compared to fossil fuels, but also compared to onshore wind.

“In onshore plants, each individual turbine produces an average of 5 MW, so to create a 40 MW park you need at least 8. With offshore, you have 15-18 MW per single turbine, so for a park with equivalent production you only need 3 – explains Della Ventura – they are blades with an average height of 220 meters and are able to optimize the wind capacity present at sea, more constant and powerful. In the future, we aim to create individual turbines of over 20 MW”.

Respect for biodiversity is not optional

If these figures suggest that offshore wind power will have a smooth path, others suggest caution in implementing it everywhere. For example, those relating to the risks that its plants may pose for marine and terrestrial biodiversity.

According to an English study published in 2024, in fact, in the construction phase, their impact is defined as "predominantly negative (52%)" especially for marine species such as sole, cod, plaice and for birds such as guillemot, northern fulmar and tufted duck.

The operational phase is less concerning, in which the effects on biodiversity can be both negative (32%) and positive (34%). Much depends on the species, the type of plant and, above all, the geographical and environmental situation in which a plant has been installed.

To let offshore wind power advance (and the European green transition) but let fish and birds live in their natural habitat, it is therefore necessary to analyse each individual context in detail, taking more time to carry out environmental assessments.

The same study says so, underlining that "in general, over 86% of the possible impacts of offshore wind power on biodiversity remains unknown". This is confirmed by Gianluca Sarà, a marine ecologist at the University of Palermo who has personally collaborated with institutions to estimate the consequences that a particular offshore wind project could have on marine flora and fauna.

“Each assessment should be divided into three, one for each component of the plant. The part that attaches to the sediments on the seabed is the one that causes the most damage, especially near the coast, because up to about 300 meters away there is greater biodiversity and many communities also used by fishing live there. Further out, the negative effects can be more limited – says Sarà – this is true in general but, in the Adriatic, it must be taken into account that the seabed is mainly composed of terrigenous mud and is home to delicate and protected species.

A pre-installation analysis of offshore wind should therefore include a particularly careful assessment of the benthic communities present, to avoid damaging those of priority importance for conservation purposes”.

There are not always negative effects and they are not always long-lasting, but in any case with the attachment of the plant to the seabed "the three-dimensional structure of the seabed inevitably changes and most of the species that live there, not having the possibility of moving, are forced to adapt to it".

Thinking about the other two components of the plants, the one that appears on the surface and the one that intervenes on the underlying water column, Sarà says he is less worried because "species capable of moving easily live there and the consequences on their conservation are less negative".

After seeing with his own eyes what the studies carried out in view of the construction of offshore wind plants are like, the ecologist remains convinced that, even if foreseen by the protocol, the protection of biodiversity is not yet a real priority both for those who invest in an offshore wind project and for those who evaluate it from the outside.

“There are still approval procedures strongly aimed at maximizing energy performance, in a serious cost-benefit study, biodiversity should appear as a fundamental component to be evaluated, not an accessory – he explains – It would add complexity but green transition and environmental protection must go hand in hand. And the ways to make this happen exist”.

The Adriatic faces wind power with Beyond

Not in the Adriatic, where offshore wind power has yet to take off, but examples of plants built taking into account pre-existing biodiversity can be found in several already operating in Northern Europe.

In the Netherlands, the Fryslan wind farm, which powers 500,000 homes north of Amsterdam, uses artificial intelligence to monitor and avoid harming seabirds such as the tern, for example, and was designed from the start with the welfare of wildlife in mind.

The same goes for the Hornsea 3 offshore wind farm in England, together with which a series of artificial nesting structures for seabirds were built as ecological compensation measures.

As for the impacts on underwater biodiversity, an example to draw inspiration from could be the artificial reefs to stimulate marine life installed near the Hollandse Kust offshore wind farm in the Netherlands, on the North Sea. Or the Kriegers Flak plant managed jointly by the Swedish state electricity company Vattenfall and the University of Aarhus in Denmark, planned from the beginning so that an experimental seafood farm could be built under the turbines.

The inclusion in the widespread network of Natura 2000 ecological sites obtained in March 2025 by Sweden for its 2.5 GW Mareld floating wind farm is yet another signal for those who are designing, evaluating or building those that will be built in the Adriatic: renewable energy plants can and must be allies of biodiversity.

To reiterate this and encourage other member countries to implement projects like those mentioned, in spring 2024 the European Union launched a 1.76 million euro interregional project (80% financed by the European Regional Development Fund) in the Mediterranean area to identify an inclusive offshore wind model that is attentive to biodiversity and local communities, as well as the number of Watts produced.

It is called Beyond and focuses on four “pilot” regions identified between Croatia and Italy. It aims to design and test new offshore wind models that produce renewable energy but do not damage biodiversity, neither in the short nor the long term. It is true that offshore wind is only now gaining ground in the Adriatic but, even more so, it is better to start off on the right foot.

This article is published in the context of the project "Cohesion4Climate" co-funded by the European Union. The EU is in no way responsible for the information or views expressed within the framework of the project; the sole responsibility for the content lies with OBCT.

Tag: Cohesion for Climate