After thirty years, Croatia is free of mines

With the final phase, thanks to the European CROSS II project, Croatia will be completely mine-free by the end of the year. We visited the Otočac woods in Lika-Senj County, one of the front lines of the 1990s war where demining is still underway. Our report

Dopo-trent-anni-la-Croazia-libera-dalle-mine-1

A Civil Protection vehicle near the demining woods near Otočac, Croatia, September 2025 - photo by Silvia Maraone

From the town of Senj on the Croatian coast, after the hairpin bends of the climb to the Vratnik Pass, a bucolic landscape unfolds: dense forests, fields of wheat, pastures of sheep and cows, and free-range horses. Among tourist homes and small stone farmhouses, in the villages of Melnice, Žuta Lokva, Brlog, and Kompolje, a few ruins gnawed by vegetation emerge, or walls of houses eroded by time and missing windows and doors. Those who have known these places well since the 1990s, unlike the tourists who pass unsuspectingly on their way to the Plitvice Lakes, recognize the still visible signs of war-related abandonment.

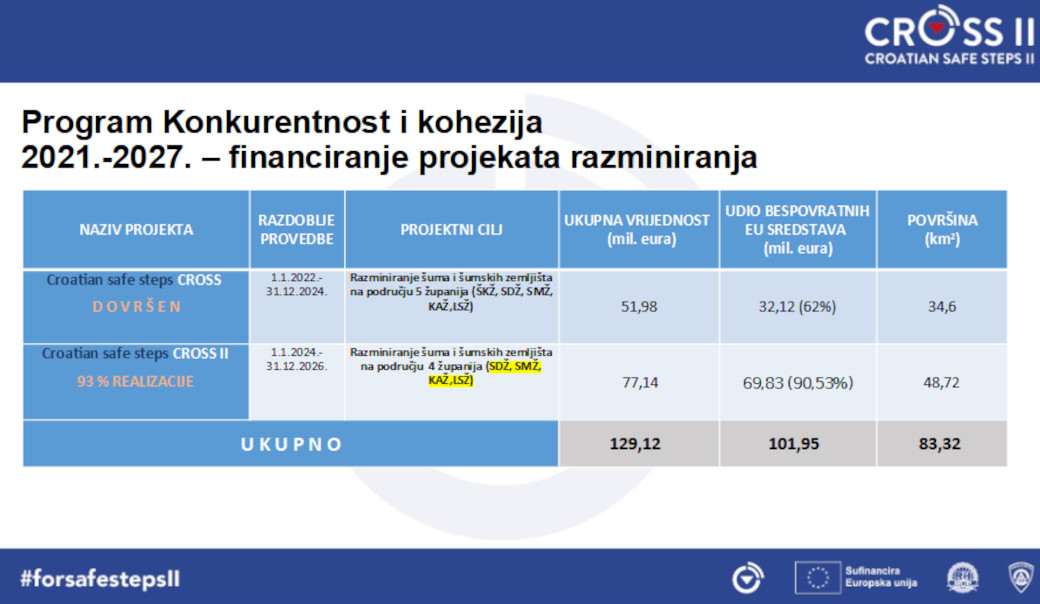

In just under an hour, you reach Otočac, Lika-Senj County, near the woods where demining is underway with the “Croatian Safe Steps CROSS II ” project, worth over €77 million. This project, co-financed by the EU under the Competitiveness and Cohesion Programme 2021-2027, began in January last year as a continuation of the previous "CROSS 2022-2024 " project.

The first gray autumn skies, humid air anticipating rain, on this late September day in Otočac, a municipality that in the 1991 census—the last before the conflict—had 16,000 inhabitants, while in 2021 it had just over half that number, not only due to the failure of displaced persons to return but also to new migrations in recent years. "After all, when you find yourself with little chance of returning and doing the job you studied for in Zagreb or abroad," a raven-haired girl who works in a bar on the main street, Kralja Zvonimira, tells me. "And then, during the war, the front line was close by, and many had already left, my parents told me…", and she adds bittersweetly, "Thank goodness it’s over and my parents have returned, but we young people are driven to look for a future elsewhere."

Not far from the "Monument to the Croatian Fallen of the Homeland War" erected in the city’s central park, the blue Civil Defense Jeep awaits me, carrying Tajana Čičak, head of the CROSS II project, and Tomislav Roviščanec. The latter, coordinator of the supervision of demining operations at the Croatian Demining Center (HCR-CTRO ) under the Civil Protection Directorate – Ministry of the Interior, points out the front line as he drives along the road northeast to Glavače: "During the war, Otočac was always under the control of our army," Tomislav explains, "But the front line begins here, with the territory once under the control of Serbian forces."

This is the part of Croatia where the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina was founded in 1991, led by Milan Babić [convicted in 2003 by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia for crimes against the Croat and non-Serb population]. And it is especially this part of the country, over which Croatia regained control with Operation "Oluja" in August 1995, that has remained the most mined.

Thirty years of mine clearance

Official data from the Ministry of the Interior – Civil Protection, provided by Roviščanec and Čičak, shows that from the 13,000 square kilometers assessed as mine-prone in 1996 by the United Nations mission, mapping work reduced the number to 1,174 square kilometers in 2005. Tomislav Roviščanec explained to me how this was achieved: “Based on information, particularly mine registers, collected by the United Nations, along with information gathered during the general investigation, we mapped the suspected areas.” Information gathered from many sources: “From military personnel, police, and all actors involved in the Homeland War who were in the area during the conflict. Also, testimonies from individuals, such as hunters and local residents… for example, if they knew where the mines had been placed, if someone was killed or injured, or if an animal had been spotted stepping on a mine, and so on.”

Among the actors involved in the war, I ask Roviščanec if information has also been exchanged with Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina: "Of course, with all parties involved in the conflict. Through bilateral relations and international cooperation, with the exchange of information on previous military positions, demarcation lines, etc."

He explains that where there is insufficient information, the UNHCR-CTRO conducts a technical inspection: "We enter the area, with specialists who search for traces of explosions, unexploded ordnance, or remnants of war. If they find mines, they move in, cordon off the area, which is then declared ‘suspected of mines.’ A preliminary plan is then developed, based on which the area in question is cleared." After collection, the information is processed, recorded, and entered into the Mine Action Center’s portal, on the MIS-portal map, where the information is constantly updated.

The process lasted three decades, in various phases, explains Tomislav Roviščanec. "The first interventions with civil defense and the army began in 1996. In 1998, the UNHCR was established, which initiated a planned demining effort: first, demining infrastructure and housing to ensure the safety of the population; then, demining agricultural land began—also with EU funding—and finally, mountainous areas, which were inaccessible and therefore left for last, were addressed."

Thanks to the numerous projects completed between 2005 and 2025, 17 square kilometers of forested areas remain to be cleared. "Therefore, with the ongoing activities, we will be able to rid Croatia of mines by the end of this year," emphasizes project manager Tajana Čičak, "while in 2026, CROSS II will complete all the final technical inspections, certifications, and other documentation. This will ensure compliance with the "National Mine Action Programme until 2026 " and with the Ottawa Convention [signed by Croatia in 1997, ed.]."

Since 1998, these operations have cost €1.107 billion, approximately 60% of which was covered by state funds and—along with loans from the World Bank and other local and foreign donors—about 26% (€286,686,344) by European funds . "European funding has grown especially since Croatia’s accession to the European Union," Tajana emphasizes, showing me the official data. In the last two projects, CROSS and CROSS II, €101.95 million was spent on a total of €129.12 million (with a non-repayable European contribution of 32.12% for the former and 69.83% for the latter) to clear a total of 82.32 square kilometers.

A complex undertaking, with CROSS II alone having so far deactivated and destroyed 1,922 antipersonnel mines, 208 antitank mines, and 230 other unexploded ordnance, including fragmentation mines, which Tomislav Roviščanec tells me are the most dangerous. These mines have become more unstable over time, especially in wooded areas: partially activated by the passage of small animals, or sunk due to soil erosion, so even the smallest wrong move is enough for them to explode.

These ordnances have claimed dozens of victims even after the war, as evidenced by official data provided to us by the MUP – Civil Protection: from 1996, especially until 2005, 207 civilian deaths and 403 injuries, and 41 deminer deaths and 95 injuries.

High-risk zone

After meeting the first emergency team with an ambulance parked on the side of the designated road, about 15 km from Otočac, we reached the second ambulance at the checkpoint, which prohibited anyone not involved in the demining operations underway here in the Smolčić Valley from entering. Along the dirt road that leads into the dense forest, red signs and tape mark the entire route that enters the "risk zone."

To ensure that no one is allowed to approach the work site, several deminers from the "DOK-ING razminiranje" and "MINA PLUS" companies joined us in a safe area of the forest, where they conducted a simulation to demonstrate the procedure. The work is scheduled on a weekly basis, in parallel in various regions of Croatia and with the involvement of local demining companies, 39 to date. The tools used are small, medium, and large. The latter, that is, machinery and tracked vehicles, cannot be used on steep terrain and in the middle of the woods like here.

"Usually, smaller tools are used, in addition to all the necessary personal safety equipment—bulletproof vest, helmet, and reinforced suit—such as metal detectors and extraction kits," Roviščanec explains to me. He adds that all the equipment is certified by the Croatian Demining Center (HCR-CTRO), which currently has 651 metal detectors, 31 medium and large machines, and 1,153 safety devices. To this are added 70 dogs, trained and then entrusted to handlers in accordance with the regulations established by law in 2007.

The sector’s workers, certified by the HCR-CTRO, number 464 in total: 47 technical assistants, 84 managers and coordinators of on-site activities, and 333 deminers. By law, a deminer can work a maximum of five hours a day. The working conditions, in addition to the fact that each mine detected by the metal detector represents a risk in itself, are aggravated by other factors: the high summer temperatures while wearing heavy safety gear, the fatigue of walking for hours on steep or bramble-filled terrain, the bites of various insects, and the long periods of separation from family members.

On the plot marked with red tape, Dalibor Barić and Ivica Kolić show me the procedure, which also involves two dogs, Nela, a 5.5-year-old female German Shepherd, and Triksi, a 5-year-old male Dutch Shepherd.

Dalibor Barić tells me that each guide has two dogs, whose training lasts about six to eight months, and their trainer takes care of them every day. The primary method, however, remains the manual detection of mines with a metal detector, probe, and equipment for clearing vegetation. Only then does a deminer come by again with a mine detector or dogs.

"After the dog has inspected the 10×10 meter square, it stops to rest and the second dog follows, following the same route, inspecting the same terrain to make sure the first dog hasn’t missed anything. After the second inspection, the square of terrain is considered cleared," Dalibor explains. He then adds: "If the dog sniffs something and smells explosives, the trainer marks the spot, then another deminer arrives and checks the area to determine what type of explosive it is." And how much work does a demining dog do? It depends on the terrain, he replies: "Usually one dog inspects five to six fields, goes to rest, and the other dog continues. On average, they inspect about ten fields a day."

Nela looks at him adoringly before being placed back in the crate on the van. A very close bond with her "guide" that, as Dalibor explains, lasts a dog’s entire working life: about nine to ten years, or less if the dog begins to work less intensively or develops health problems.

Ivica Kolić shows me the work with metal detectors and small extraction tools, which requires maximum concentration, a steady hand, and composure, despite the high level of psychological pressure. He walks slowly with the metal detector, and if it starts to beep, he proceeds to the next stage. He bends down to test the surface with the probe rod held at a 45-degree angle to determine which mine it is. At that point, the deactivation and destruction mode is programmed. Regarding this, Tomislav Roviščanec explains: "The contracted companies are required by law to destroy them during the work. Therefore, the found mines are not taken away: if they are already damaged, they are destroyed on site by controlled detonation, that is, by surrounding them with sandbags; if they are undamaged, they are destroyed in a designated location."

The deminers present tell me they have been doing this work for many years. At least, Tajana Čičak informs me, since it’s a highly demanding job, eighteen months are counted for every twelve months worked, meaning a vast majority of Croatian deminers will retire by 2026.

As I say goodbye to them, I ask how they’ve managed to withstand such psychological pressure for so long. "Well, it’s difficult," Ivica replies with a sigh, "especially when one of your colleagues dies." Although the number of deminers killed or injured has decreased dramatically since 2005, sadly, the last case dates back to the end of July. Matej Robić lost his life in Oštarije, during the clearing of an area not included in the CROSS II project: a former Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) barracks mined by "Yugoslav" soldiers in 1991, before abandoning it.

We set off again for Otočac, along a provincial road where nature reigns supreme. On the sides, only dense forests of trees tens of meters tall and thick undergrowth that have not seen human footsteps for thirty years and which from 2026 will finally return to being a zone free of lethal explosives.

This article is published as part of the Cohesion4Climate project, co-funded by the European Union. The EU is in no way responsible for the information or views expressed within the project; the responsibility lies solely with OBCT.

Per approfondire

Read some recent OBCT articles on the topic: "Croatia, mines still kill" and "Croatia, Fearless project: demining completed" (February and May 2023).

Go to the photo gallery of the reportage in the woods around Otočac, where demining was underway as part of the CROSS II project.

Tag: Cohesion for Climate | EU Cohesion | Mines

Featured articles

After thirty years, Croatia is free of mines

With the final phase, thanks to the European CROSS II project, Croatia will be completely mine-free by the end of the year. We visited the Otočac woods in Lika-Senj County, one of the front lines of the 1990s war where demining is still underway. Our report

Dopo-trent-anni-la-Croazia-libera-dalle-mine-1

A Civil Protection vehicle near the demining woods near Otočac, Croatia, September 2025 - photo by Silvia Maraone

From the town of Senj on the Croatian coast, after the hairpin bends of the climb to the Vratnik Pass, a bucolic landscape unfolds: dense forests, fields of wheat, pastures of sheep and cows, and free-range horses. Among tourist homes and small stone farmhouses, in the villages of Melnice, Žuta Lokva, Brlog, and Kompolje, a few ruins gnawed by vegetation emerge, or walls of houses eroded by time and missing windows and doors. Those who have known these places well since the 1990s, unlike the tourists who pass unsuspectingly on their way to the Plitvice Lakes, recognize the still visible signs of war-related abandonment.

In just under an hour, you reach Otočac, Lika-Senj County, near the woods where demining is underway with the “Croatian Safe Steps CROSS II ” project, worth over €77 million. This project, co-financed by the EU under the Competitiveness and Cohesion Programme 2021-2027, began in January last year as a continuation of the previous "CROSS 2022-2024 " project.

The first gray autumn skies, humid air anticipating rain, on this late September day in Otočac, a municipality that in the 1991 census—the last before the conflict—had 16,000 inhabitants, while in 2021 it had just over half that number, not only due to the failure of displaced persons to return but also to new migrations in recent years. "After all, when you find yourself with little chance of returning and doing the job you studied for in Zagreb or abroad," a raven-haired girl who works in a bar on the main street, Kralja Zvonimira, tells me. "And then, during the war, the front line was close by, and many had already left, my parents told me…", and she adds bittersweetly, "Thank goodness it’s over and my parents have returned, but we young people are driven to look for a future elsewhere."

Not far from the "Monument to the Croatian Fallen of the Homeland War" erected in the city’s central park, the blue Civil Defense Jeep awaits me, carrying Tajana Čičak, head of the CROSS II project, and Tomislav Roviščanec. The latter, coordinator of the supervision of demining operations at the Croatian Demining Center (HCR-CTRO ) under the Civil Protection Directorate – Ministry of the Interior, points out the front line as he drives along the road northeast to Glavače: "During the war, Otočac was always under the control of our army," Tomislav explains, "But the front line begins here, with the territory once under the control of Serbian forces."

This is the part of Croatia where the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina was founded in 1991, led by Milan Babić [convicted in 2003 by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia for crimes against the Croat and non-Serb population]. And it is especially this part of the country, over which Croatia regained control with Operation "Oluja" in August 1995, that has remained the most mined.

Thirty years of mine clearance

Official data from the Ministry of the Interior – Civil Protection, provided by Roviščanec and Čičak, shows that from the 13,000 square kilometers assessed as mine-prone in 1996 by the United Nations mission, mapping work reduced the number to 1,174 square kilometers in 2005. Tomislav Roviščanec explained to me how this was achieved: “Based on information, particularly mine registers, collected by the United Nations, along with information gathered during the general investigation, we mapped the suspected areas.” Information gathered from many sources: “From military personnel, police, and all actors involved in the Homeland War who were in the area during the conflict. Also, testimonies from individuals, such as hunters and local residents… for example, if they knew where the mines had been placed, if someone was killed or injured, or if an animal had been spotted stepping on a mine, and so on.”

Among the actors involved in the war, I ask Roviščanec if information has also been exchanged with Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina: "Of course, with all parties involved in the conflict. Through bilateral relations and international cooperation, with the exchange of information on previous military positions, demarcation lines, etc."

He explains that where there is insufficient information, the UNHCR-CTRO conducts a technical inspection: "We enter the area, with specialists who search for traces of explosions, unexploded ordnance, or remnants of war. If they find mines, they move in, cordon off the area, which is then declared ‘suspected of mines.’ A preliminary plan is then developed, based on which the area in question is cleared." After collection, the information is processed, recorded, and entered into the Mine Action Center’s portal, on the MIS-portal map, where the information is constantly updated.

The process lasted three decades, in various phases, explains Tomislav Roviščanec. "The first interventions with civil defense and the army began in 1996. In 1998, the UNHCR was established, which initiated a planned demining effort: first, demining infrastructure and housing to ensure the safety of the population; then, demining agricultural land began—also with EU funding—and finally, mountainous areas, which were inaccessible and therefore left for last, were addressed."

Thanks to the numerous projects completed between 2005 and 2025, 17 square kilometers of forested areas remain to be cleared. "Therefore, with the ongoing activities, we will be able to rid Croatia of mines by the end of this year," emphasizes project manager Tajana Čičak, "while in 2026, CROSS II will complete all the final technical inspections, certifications, and other documentation. This will ensure compliance with the "National Mine Action Programme until 2026 " and with the Ottawa Convention [signed by Croatia in 1997, ed.]."

Since 1998, these operations have cost €1.107 billion, approximately 60% of which was covered by state funds and—along with loans from the World Bank and other local and foreign donors—about 26% (€286,686,344) by European funds . "European funding has grown especially since Croatia’s accession to the European Union," Tajana emphasizes, showing me the official data. In the last two projects, CROSS and CROSS II, €101.95 million was spent on a total of €129.12 million (with a non-repayable European contribution of 32.12% for the former and 69.83% for the latter) to clear a total of 82.32 square kilometers.

A complex undertaking, with CROSS II alone having so far deactivated and destroyed 1,922 antipersonnel mines, 208 antitank mines, and 230 other unexploded ordnance, including fragmentation mines, which Tomislav Roviščanec tells me are the most dangerous. These mines have become more unstable over time, especially in wooded areas: partially activated by the passage of small animals, or sunk due to soil erosion, so even the smallest wrong move is enough for them to explode.

These ordnances have claimed dozens of victims even after the war, as evidenced by official data provided to us by the MUP – Civil Protection: from 1996, especially until 2005, 207 civilian deaths and 403 injuries, and 41 deminer deaths and 95 injuries.

High-risk zone

After meeting the first emergency team with an ambulance parked on the side of the designated road, about 15 km from Otočac, we reached the second ambulance at the checkpoint, which prohibited anyone not involved in the demining operations underway here in the Smolčić Valley from entering. Along the dirt road that leads into the dense forest, red signs and tape mark the entire route that enters the "risk zone."

To ensure that no one is allowed to approach the work site, several deminers from the "DOK-ING razminiranje" and "MINA PLUS" companies joined us in a safe area of the forest, where they conducted a simulation to demonstrate the procedure. The work is scheduled on a weekly basis, in parallel in various regions of Croatia and with the involvement of local demining companies, 39 to date. The tools used are small, medium, and large. The latter, that is, machinery and tracked vehicles, cannot be used on steep terrain and in the middle of the woods like here.

"Usually, smaller tools are used, in addition to all the necessary personal safety equipment—bulletproof vest, helmet, and reinforced suit—such as metal detectors and extraction kits," Roviščanec explains to me. He adds that all the equipment is certified by the Croatian Demining Center (HCR-CTRO), which currently has 651 metal detectors, 31 medium and large machines, and 1,153 safety devices. To this are added 70 dogs, trained and then entrusted to handlers in accordance with the regulations established by law in 2007.

The sector’s workers, certified by the HCR-CTRO, number 464 in total: 47 technical assistants, 84 managers and coordinators of on-site activities, and 333 deminers. By law, a deminer can work a maximum of five hours a day. The working conditions, in addition to the fact that each mine detected by the metal detector represents a risk in itself, are aggravated by other factors: the high summer temperatures while wearing heavy safety gear, the fatigue of walking for hours on steep or bramble-filled terrain, the bites of various insects, and the long periods of separation from family members.

On the plot marked with red tape, Dalibor Barić and Ivica Kolić show me the procedure, which also involves two dogs, Nela, a 5.5-year-old female German Shepherd, and Triksi, a 5-year-old male Dutch Shepherd.

Dalibor Barić tells me that each guide has two dogs, whose training lasts about six to eight months, and their trainer takes care of them every day. The primary method, however, remains the manual detection of mines with a metal detector, probe, and equipment for clearing vegetation. Only then does a deminer come by again with a mine detector or dogs.

"After the dog has inspected the 10×10 meter square, it stops to rest and the second dog follows, following the same route, inspecting the same terrain to make sure the first dog hasn’t missed anything. After the second inspection, the square of terrain is considered cleared," Dalibor explains. He then adds: "If the dog sniffs something and smells explosives, the trainer marks the spot, then another deminer arrives and checks the area to determine what type of explosive it is." And how much work does a demining dog do? It depends on the terrain, he replies: "Usually one dog inspects five to six fields, goes to rest, and the other dog continues. On average, they inspect about ten fields a day."

Nela looks at him adoringly before being placed back in the crate on the van. A very close bond with her "guide" that, as Dalibor explains, lasts a dog’s entire working life: about nine to ten years, or less if the dog begins to work less intensively or develops health problems.

Ivica Kolić shows me the work with metal detectors and small extraction tools, which requires maximum concentration, a steady hand, and composure, despite the high level of psychological pressure. He walks slowly with the metal detector, and if it starts to beep, he proceeds to the next stage. He bends down to test the surface with the probe rod held at a 45-degree angle to determine which mine it is. At that point, the deactivation and destruction mode is programmed. Regarding this, Tomislav Roviščanec explains: "The contracted companies are required by law to destroy them during the work. Therefore, the found mines are not taken away: if they are already damaged, they are destroyed on site by controlled detonation, that is, by surrounding them with sandbags; if they are undamaged, they are destroyed in a designated location."

The deminers present tell me they have been doing this work for many years. At least, Tajana Čičak informs me, since it’s a highly demanding job, eighteen months are counted for every twelve months worked, meaning a vast majority of Croatian deminers will retire by 2026.

As I say goodbye to them, I ask how they’ve managed to withstand such psychological pressure for so long. "Well, it’s difficult," Ivica replies with a sigh, "especially when one of your colleagues dies." Although the number of deminers killed or injured has decreased dramatically since 2005, sadly, the last case dates back to the end of July. Matej Robić lost his life in Oštarije, during the clearing of an area not included in the CROSS II project: a former Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) barracks mined by "Yugoslav" soldiers in 1991, before abandoning it.

We set off again for Otočac, along a provincial road where nature reigns supreme. On the sides, only dense forests of trees tens of meters tall and thick undergrowth that have not seen human footsteps for thirty years and which from 2026 will finally return to being a zone free of lethal explosives.

This article is published as part of the Cohesion4Climate project, co-funded by the European Union. The EU is in no way responsible for the information or views expressed within the project; the responsibility lies solely with OBCT.

Per approfondire

Read some recent OBCT articles on the topic: "Croatia, mines still kill" and "Croatia, Fearless project: demining completed" (February and May 2023).

Go to the photo gallery of the reportage in the woods around Otočac, where demining was underway as part of the CROSS II project.

Tag: Cohesion for Climate | EU Cohesion | Mines