The Dildilians: an Armenian family between history and photography

An Armenian family whose destiny is intertwined with photography and Turkey’s complex history. An interview with Armen Marsoobian, professor of philosophy and editor of Metaphilosophy magazine, a descendant of the Dildilian family, and himself a passionate photographer and collector

I-Dildilian-una-famiglia-armena-tra-storia-e-fotografia-1

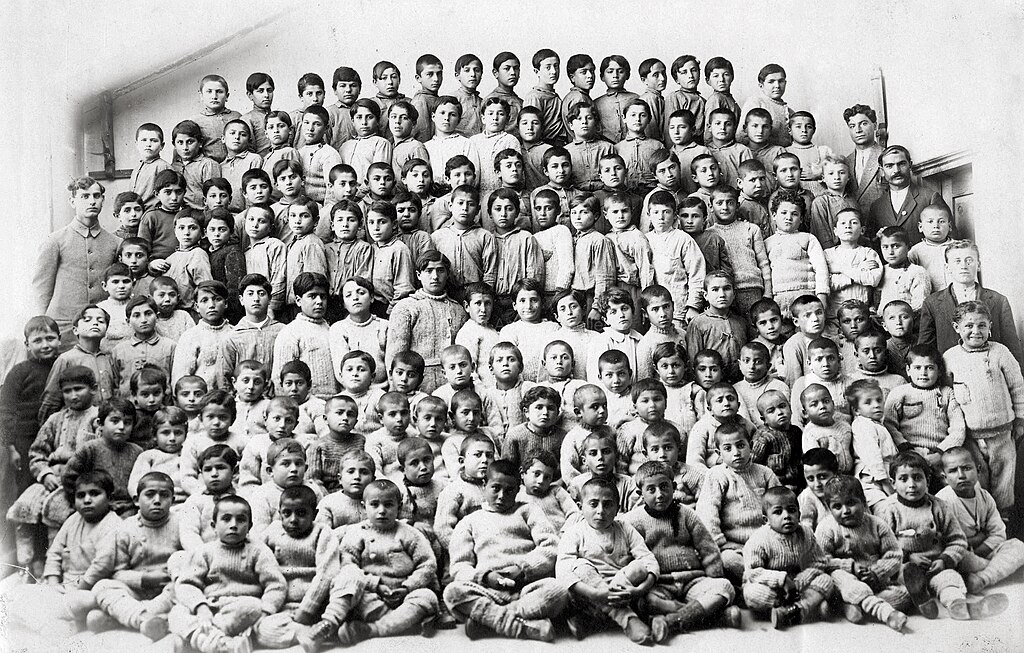

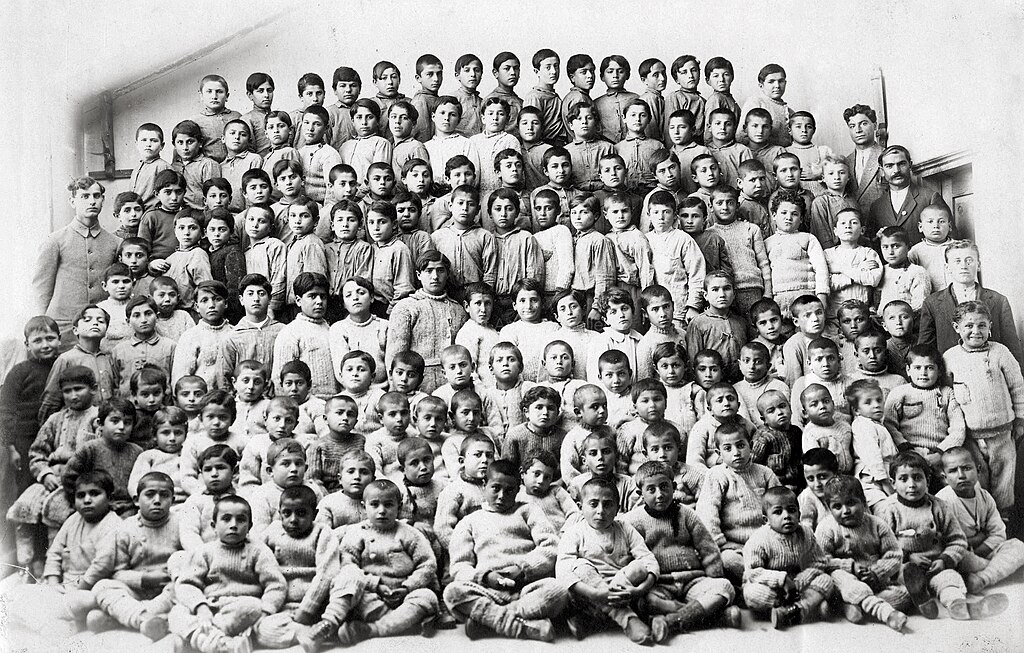

Armenian orphans, Tsolag Dildilian (photo Wikimedia commons )

Where does the Dildilian family, of which you are a descendant, have its roots? Where does your connection with photography come from?

My ancestors came from what is now the Anatolian city of Sivas, formerly Sebastia. Over the centuries, they earned a living as blacksmiths, pastry chefs, and shoemakers. The turning point came in 1888 when my grandfather Tsolag decided to take up photography as a profession. He had artistic inclinations and couldn’t see himself working as a cobbler in the family business. His father Krikor initially resisted but soon gave up, giving his son a large-format camera. After a brief apprenticeship, Tsolag took his first photo, a portrait of his younger brother Aram.

The transition from amateur to professional wasn’t easy for Tsolag. It required darkroom equipment and the help of an expert. Krikor came to his aid once again, contacting a well-known Armenian photographer working in what was then Constantinople, one Mikael Natourian. With the promise of a cash reward, obtained by mortgaging the family home, Krikor invited him to move to Sivas and asked him to set up a photography studio with his son. At that point, Tsolag had everything he needed to begin his photographic adventure: the Natourian-Dildilian studio was born.

Now a brief digression. In the territories of the Ottoman Empire, Armenians held a near monopoly in the photography industry. How can this preponderance be explained?

There are various hypotheses. Sunni Islam’s aversion to the representation of images hindered the entry of Muslims into the nascent photography market in the mid-19th century, thus allowing minorities to dominate the industry from the very beginning.

Many Armenians practiced the professions of pharmacists and goldsmiths, and therefore had the materials and knowledge to more easily transition to the photographic medium. The techniques of the time required a certain familiarity with the chemical processes necessary for developing and printing.

Finally, the lively cultural exchange between ethnic and religious minorities and Europe should not be underestimated. Armenians, Greeks, and Jews were informed and influenced by what was happening in the Old World, more than the Turks were, and photographic art was no exception.

In recent years, the history of photography in the Ottoman Empire has seen renewed interest from the academic world, yet research has focused primarily on photography studios in large cities. Therefore, the stories and images of photographers who worked on the periphery of the empire, just like the Dildilians, remain unknown to most.

My family’s history is dear to me not only for sentimental reasons, but above all because it is intertwined with the destinies of the Armenian people in Anatolia.

Let’s return to Tsolag. How did your career begin?

At the time, it was fashionable for the wealthiest people to have their portraits taken. Krikor was a wealthy man with high-level connections. Tsolag and Mikael’s first clients were local notables.

The studio’s fame soon spread to the surrounding provinces. In 1890, the duo decided to move to Merzifon, a town in the Black Sea region. Shortly after the move, Mikael died, leaving Tsolag solely responsible for the future of the business.

There was no shortage of work in Merzifon, thanks to the presence of Anatolia College, an educational institution founded by American Protestant missionaries. The complex also included a seminary, an orphanage, and a hospital. The college’s administration was in constant need of images: graduation ceremonies, class photos, for school yearbooks, and for advertising purposes.

The collaboration with Tsolag became so intense that in 1894 he was hired directly as the official photographer. Business was booming, so much so that his cousin Sumpad opened a practice in Samsun. The same was true for his private life. Tsolag married Mariam, a girl originally from Elazığ, and had an elegant, traditional-style residence built near the college.

It was during those very years (1894-1897) that the Hamidian massacres occurred in Anatolia. What happened to the Dildilian family?

Those were difficult years for the Armenian minority. In Merzifon itself and throughout Anatolia, popular uprisings occurred, often bloodily repressed by the Ottoman authorities. Fortunately, the Dildilians managed to survive that period unscathed. Some members of the family had previously abandoned the Armenian Apostolic Church for the Protestant Church, which granted them a sort of immunity.

The Dildilians, like many other Armenians, were characterized by a strong entrepreneurial spirit. They had ideas and knew how to make them profitable, often and willingly they became rich, generating envy among the Turkish-Muslim majority. This

This resentment, combined with a spirit of revanchism, resurfaced in a much more bloody manner from 1915 to 1923, causing the Medz Yeghern, the Great Crime, the tragedy that almost completely depopulated Anatolia of Armenians.

When and how did the Dildilians abandon Anatolia? And how did they manage to preserve their photographic archive?

On August 6, 1915, a high-ranking Ottoman officer warned Tsolag that a roundup would soon be taking place. There was only one option left for survival: conversion to Islam. There was no time to waste. The men of the family went to the Merzifon town hall where they recited their profession of faith before the local mufti, effectively becoming Muslims.

For the Dildilian family, daily life became a constant compromise. Religious holidays were celebrated in secret. To support themselves, Tsolag and Aram had to work as photographers for political authorities and even the army. In those years, hundreds of thousands of Armenians were deported to Anatolia and perished during the so-called death marches. All around was nothing but death and destruction. With the help of Near East Relief, an American charity, the two at least managed to open an orphanage, as evidenced by some splendid and moving portraits.

Further massacres in Merzifon and family turmoil forced the family to seek refuge in Samsun. In November 1922, emissaries from Near East Relief informed Aram of the imminent arrival of a ship, the SS Belgravia, which would rescue as many refugees and orphans as possible.

The Dildilians hastily decided to abandon Anatolia forever; in all likelihood, such an opportunity would never arise again. In just under 24 hours, they packed their bags and took with them as many negative plates as possible, stealing space from other personal items — a clear act of love for photography. After a complicated journey, through Odessa and Istanbul, they landed in Athens.

From then on, the family split: some remained in Greece, others emigrated to France, and others found themselves overseas, eventually becoming part of the vast Armenian diaspora.

A selection of photographs from the Dildilian archive has previously been exhibited in Turkey. What can you tell us about it?

Between 2013 and 2015, the cities of Istanbul, Merzifon, Diyarbakır, and Ankara hosted a traveling exhibition. Given the sensitive subject matter, organizing such an exhibition was not easy. There were misunderstandings with the authorities and controversy with the press, but we succeeded. Of course, in those years the political climate was more favorable, less hostile than today. Having said that, I would like to thank Osman Kavala; without his support, this project would never have become a reality.

Featured articles

The Dildilians: an Armenian family between history and photography

An Armenian family whose destiny is intertwined with photography and Turkey’s complex history. An interview with Armen Marsoobian, professor of philosophy and editor of Metaphilosophy magazine, a descendant of the Dildilian family, and himself a passionate photographer and collector

I-Dildilian-una-famiglia-armena-tra-storia-e-fotografia-1

Armenian orphans, Tsolag Dildilian (photo Wikimedia commons )

Where does the Dildilian family, of which you are a descendant, have its roots? Where does your connection with photography come from?

My ancestors came from what is now the Anatolian city of Sivas, formerly Sebastia. Over the centuries, they earned a living as blacksmiths, pastry chefs, and shoemakers. The turning point came in 1888 when my grandfather Tsolag decided to take up photography as a profession. He had artistic inclinations and couldn’t see himself working as a cobbler in the family business. His father Krikor initially resisted but soon gave up, giving his son a large-format camera. After a brief apprenticeship, Tsolag took his first photo, a portrait of his younger brother Aram.

The transition from amateur to professional wasn’t easy for Tsolag. It required darkroom equipment and the help of an expert. Krikor came to his aid once again, contacting a well-known Armenian photographer working in what was then Constantinople, one Mikael Natourian. With the promise of a cash reward, obtained by mortgaging the family home, Krikor invited him to move to Sivas and asked him to set up a photography studio with his son. At that point, Tsolag had everything he needed to begin his photographic adventure: the Natourian-Dildilian studio was born.

Now a brief digression. In the territories of the Ottoman Empire, Armenians held a near monopoly in the photography industry. How can this preponderance be explained?

There are various hypotheses. Sunni Islam’s aversion to the representation of images hindered the entry of Muslims into the nascent photography market in the mid-19th century, thus allowing minorities to dominate the industry from the very beginning.

Many Armenians practiced the professions of pharmacists and goldsmiths, and therefore had the materials and knowledge to more easily transition to the photographic medium. The techniques of the time required a certain familiarity with the chemical processes necessary for developing and printing.

Finally, the lively cultural exchange between ethnic and religious minorities and Europe should not be underestimated. Armenians, Greeks, and Jews were informed and influenced by what was happening in the Old World, more than the Turks were, and photographic art was no exception.

In recent years, the history of photography in the Ottoman Empire has seen renewed interest from the academic world, yet research has focused primarily on photography studios in large cities. Therefore, the stories and images of photographers who worked on the periphery of the empire, just like the Dildilians, remain unknown to most.

My family’s history is dear to me not only for sentimental reasons, but above all because it is intertwined with the destinies of the Armenian people in Anatolia.

Let’s return to Tsolag. How did your career begin?

At the time, it was fashionable for the wealthiest people to have their portraits taken. Krikor was a wealthy man with high-level connections. Tsolag and Mikael’s first clients were local notables.

The studio’s fame soon spread to the surrounding provinces. In 1890, the duo decided to move to Merzifon, a town in the Black Sea region. Shortly after the move, Mikael died, leaving Tsolag solely responsible for the future of the business.

There was no shortage of work in Merzifon, thanks to the presence of Anatolia College, an educational institution founded by American Protestant missionaries. The complex also included a seminary, an orphanage, and a hospital. The college’s administration was in constant need of images: graduation ceremonies, class photos, for school yearbooks, and for advertising purposes.

The collaboration with Tsolag became so intense that in 1894 he was hired directly as the official photographer. Business was booming, so much so that his cousin Sumpad opened a practice in Samsun. The same was true for his private life. Tsolag married Mariam, a girl originally from Elazığ, and had an elegant, traditional-style residence built near the college.

It was during those very years (1894-1897) that the Hamidian massacres occurred in Anatolia. What happened to the Dildilian family?

Those were difficult years for the Armenian minority. In Merzifon itself and throughout Anatolia, popular uprisings occurred, often bloodily repressed by the Ottoman authorities. Fortunately, the Dildilians managed to survive that period unscathed. Some members of the family had previously abandoned the Armenian Apostolic Church for the Protestant Church, which granted them a sort of immunity.

The Dildilians, like many other Armenians, were characterized by a strong entrepreneurial spirit. They had ideas and knew how to make them profitable, often and willingly they became rich, generating envy among the Turkish-Muslim majority. This

This resentment, combined with a spirit of revanchism, resurfaced in a much more bloody manner from 1915 to 1923, causing the Medz Yeghern, the Great Crime, the tragedy that almost completely depopulated Anatolia of Armenians.

When and how did the Dildilians abandon Anatolia? And how did they manage to preserve their photographic archive?

On August 6, 1915, a high-ranking Ottoman officer warned Tsolag that a roundup would soon be taking place. There was only one option left for survival: conversion to Islam. There was no time to waste. The men of the family went to the Merzifon town hall where they recited their profession of faith before the local mufti, effectively becoming Muslims.

For the Dildilian family, daily life became a constant compromise. Religious holidays were celebrated in secret. To support themselves, Tsolag and Aram had to work as photographers for political authorities and even the army. In those years, hundreds of thousands of Armenians were deported to Anatolia and perished during the so-called death marches. All around was nothing but death and destruction. With the help of Near East Relief, an American charity, the two at least managed to open an orphanage, as evidenced by some splendid and moving portraits.

Further massacres in Merzifon and family turmoil forced the family to seek refuge in Samsun. In November 1922, emissaries from Near East Relief informed Aram of the imminent arrival of a ship, the SS Belgravia, which would rescue as many refugees and orphans as possible.

The Dildilians hastily decided to abandon Anatolia forever; in all likelihood, such an opportunity would never arise again. In just under 24 hours, they packed their bags and took with them as many negative plates as possible, stealing space from other personal items — a clear act of love for photography. After a complicated journey, through Odessa and Istanbul, they landed in Athens.

From then on, the family split: some remained in Greece, others emigrated to France, and others found themselves overseas, eventually becoming part of the vast Armenian diaspora.

A selection of photographs from the Dildilian archive has previously been exhibited in Turkey. What can you tell us about it?

Between 2013 and 2015, the cities of Istanbul, Merzifon, Diyarbakır, and Ankara hosted a traveling exhibition. Given the sensitive subject matter, organizing such an exhibition was not easy. There were misunderstandings with the authorities and controversy with the press, but we succeeded. Of course, in those years the political climate was more favorable, less hostile than today. Having said that, I would like to thank Osman Kavala; without his support, this project would never have become a reality.