Zla Mavka: How Ukrainian women fight Russia’s occupation

Zla Mavka is a grassroots network of Ukrainian women operating under occupation. Named after mythical Ukrainian forest spirits known for their wild and mysterious nature, the Mavkas represent a nonviolent resistance movement

Zla-Mavka-le-donne-ucraine-resistono-all-occupazione-russa-1

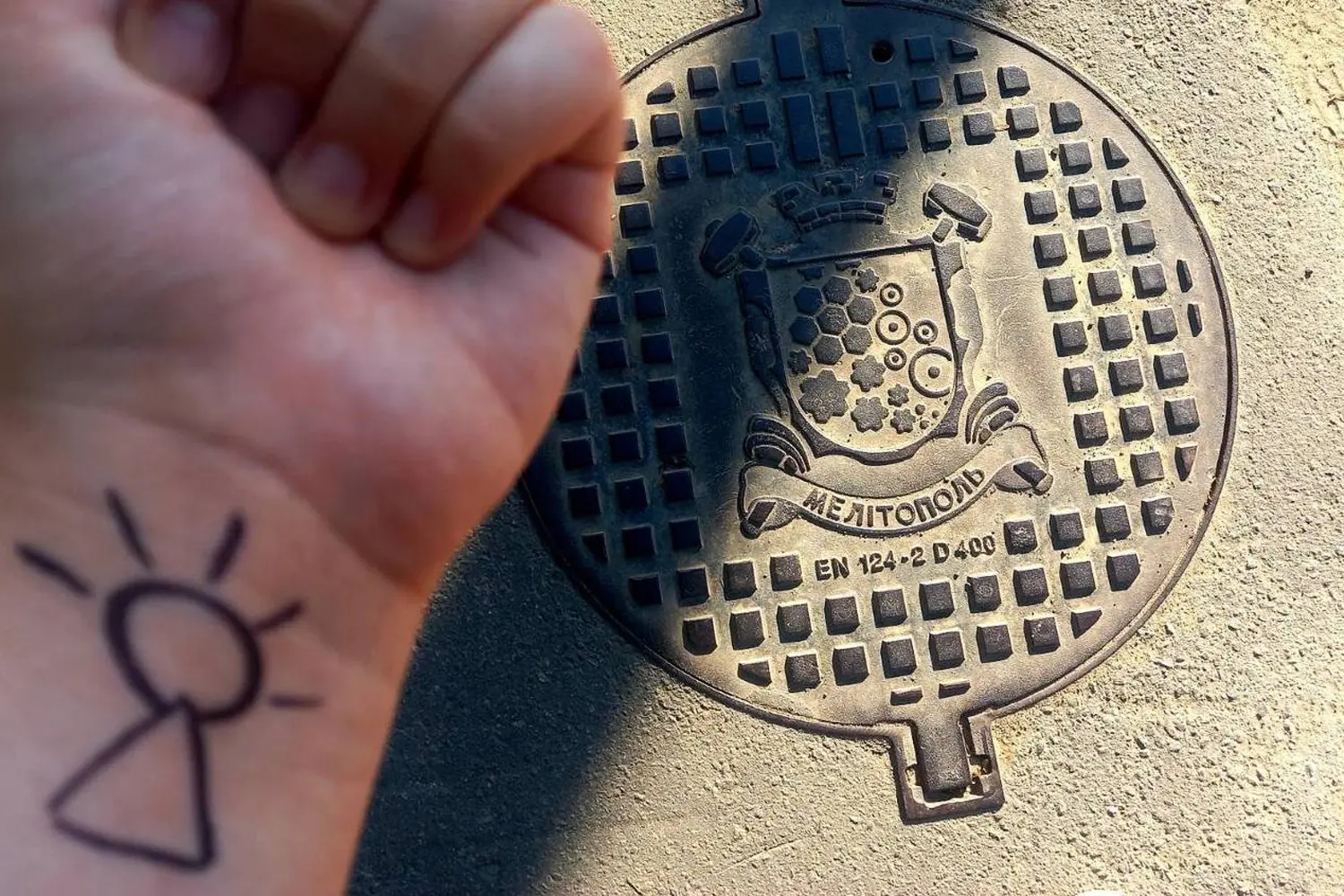

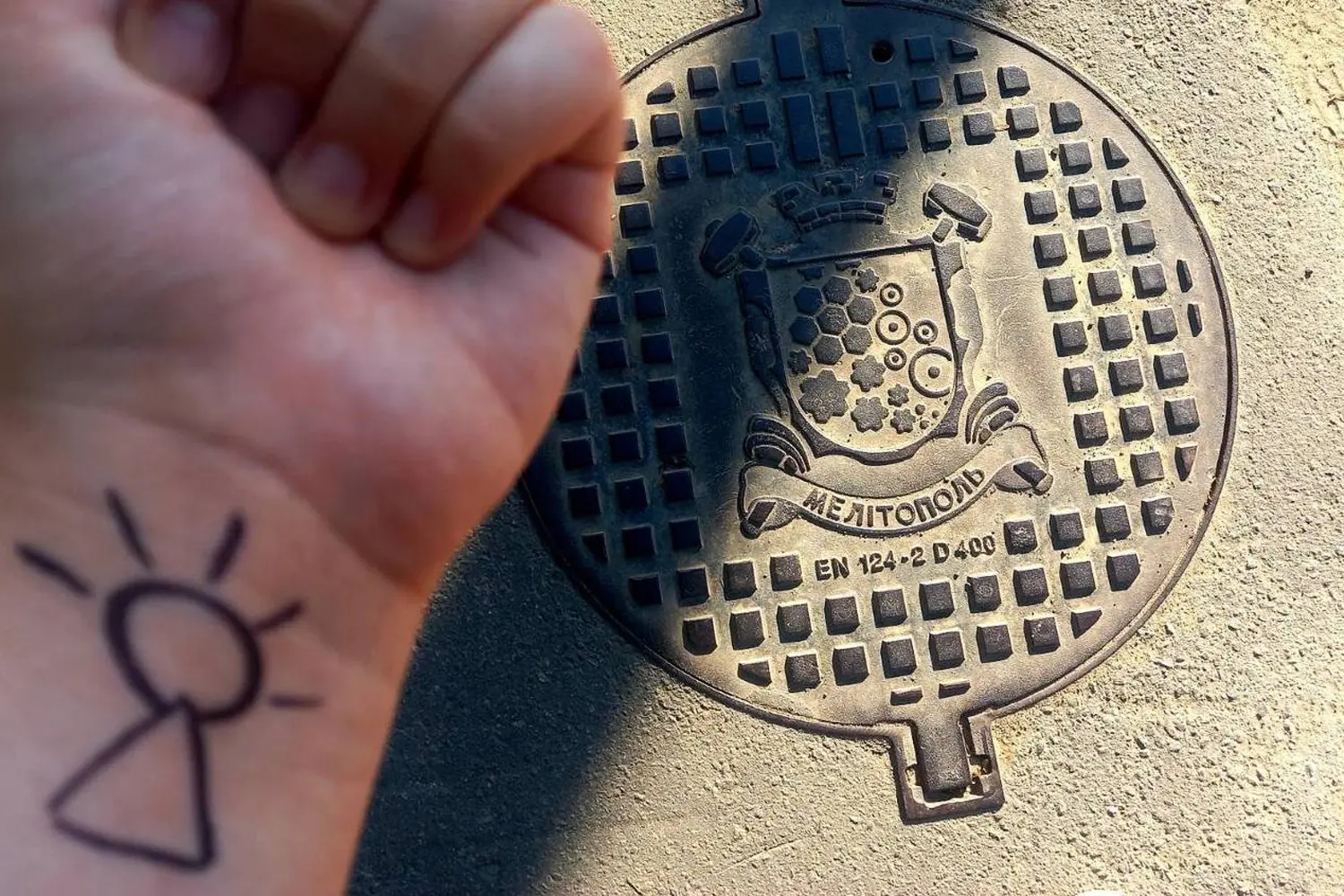

Melitopol, Ukraine - photo Zla Mavka

In a modest kitchen in occupied Melitopol, Ukraine, a small group of women met in early 2023 to discuss a question that had come to dominate life in their city: how to resist.

Melitopol, a strategic city in southeastern Ukraine, had been under Russian military occupation for nearly a year by then. With Ukrainian flags torn down, pro-Kremlin authorities installed and media replaced by Russian state television, everyday life was becoming unrecognizable. But in that quiet meeting, a form of resistance began to take shape, involving women and non-violence.

That meeting led to the formation of Zla Mavka (Angry Mavkas or Angry Fairies), a grassroots network of Ukrainian women operating under occupation. Named after mythical Ukrainian forest spirits known for their wild and mysterious nature, the Mavkas represent a nonviolent resistance movement. Their aim is to preserve Ukrainian identity, culture and morale in a city where the occupiers want to erase them.

The City Under Occupation

Melitopol, a city of roughly 150,000 residents before the Russian full-scale war, sits at an important junction in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, southern Ukraine. It links Crimea, a peninsula that Russia occupied back in 2014, with the eastern regions of Ukraine, which have also been under the Russian control.

When Russian troops swept into the south in the opening weeks of the full-scale invasion that began on 24 February, 2022, Melitopol was quickly occupied. By 1 March, the Russian military had established control of the city, replacing local government officials with pro-Russian administrators.

From the outset, the occupation was marked by repression. Ukrainian-language signs were removed, protests were suppressed and dozens of residents – including journalists, activists and civil servants – were detained or disappeared. Russian forces introduced their own school curricula, broadcast Kremlin-controlled media and began issuing Russian passports to encourage “integration” – the locals had to become Russian citizens, otherwise they faced severe consequences from the occupying authorities.

Despite these efforts, many residents refused to adapt. Civil resistance – though often quiet and invisible – persisted, and in some cases, intensified. This was the case with Angry Mavkas.

This movement is not a typical undercover initiative, meaning that it does not involve soldiers or militants, and it focuses on non-violent resident. The movement unites women, many of whom are mothers or caregivers, and chose to remain in their city even as others fled. Their resistance takes the form of underground newspapers, symbolic protest actions and the distribution of factual information to combat Russian disinformation.

“The Russians expect passivity”, says the group’s anonymous founder, “they believe that occupation will become normal over time. We are here to make sure it never feels normal”.

Their underground newspaper is a central pillar of their work. It offers updates about the war, reminders of Ukrainian national holidays and short texts on history and identity. It is printed discreetly and hand-distributed – often left in mailboxes, on benches or inside apartment buildings. The goal is to reach people, especially those who do not have access to the Internet or depend on Russian-controlled television – often the elderly.

“People who only watch Russian TV start to believe what they hear”, explains the founder. “Our newspaper is meant to interrupt that and remind people that Ukraine has not disappeared.”

Another tactic is that of symbolic protest. The group has distributed fake Russian rubles with anti-war messages, placed pumpkins at the doors of well-known collaborators and painted small Ukrainian flags in alleyways and on electricity poles. These acts are often dismissed as mere pranks by occupying forces, but they carry significant meaning for locals. They signal that resistance is still alive and that Ukraine is not forgotten.

Risk and Surveillance

Operating under occupation is dangerous. Russian forces in Melitopol have carried out raids on suspected resistance members, detained civilians for social media posts and forced detainees to record public “confession” videos in which they denounce their actions. Detainees are often transferred to Crimea or Russia, where legal protections are minimal.

The Mavkas are aware of the risks.

“It only takes one mistake”, admits the founder. “That could be leaving your phone unsecured, trusting the wrong person or being in the wrong place when a patrol passes by”.

To minimize risk, the group operates using strict security protocols. Communication is limited, members use pseudonyms and activities are compartmentalized. Nobody knows everything. So far, the group has avoided arrests, which they attribute to discipline and constant vigilance.

“We live with fear”, says one member. “But fear does not have to mean silence”.

Members of Angry Mavkas are driven by a range of motivations. Some have lost family members in the war. Others were involved in civil society before the invasion. For many, the motivation is simpler: a refusal to accept the occupation of their city and the destruction of their national identity.

The group has expanded beyond Melitopol, with small cells now operating in other occupied areas of southern Ukraine, including parts of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts as well as Crimean Peninsula. Each group works independently to reduce exposure. While they share general goals, coordination is limited and indirect.

One of the group’s most personal projects is “The Mavka Diaries”, a collection of anonymous testimonies written by women living under occupation. These stories – published through secure online channels and in limited edition – document daily life, from navigating Russian checkpoints to the psychological effects of isolation. The diaries have been shared with Ukrainian media and international human rights organizations, providing insight into life behind enemy lines.

“People outside the occupation zone often ask us basic questions: ‘Do you have electricity? Is there food?’”, says the founder. “These diaries are a way to show that we are not just surviving. We are resisting”.

The work of Angry Mavkas is part of a larger pattern of civil resistance across occupied Ukraine. In the early days of the invasion, mass protests broke out in cities like Kherson, Berdiansk and Melitopol. After the repression of these protests, resistance became more covert: small groups, coded message and underground networks working to keep the idea of Ukraine alive.

The Ukrainian government has acknowledged the role of local resistance, with President Volodymyr Zelenskyy repeatedly praising those who “continue to fight” in silence. These groups are not formally part of the Ukrainian military, but are seen as a vital component of the country’s broader defense.

As the full-scale war enters its fourth year, Melitopol remains under Russian control, though it is frequently cited by Ukrainian military analysts as a critical target for future operations. Located on the so-called “land bridge” between Russia and Crimea, the city’s liberation would strike a strategic blow to Russian logistics.

Until that happens, the residents who resist remain hopeful.

“Our city is occupied”, says the founder, “but not our identity. That is what we are protecting”.

Tag: Donne 2

Zla Mavka: How Ukrainian women fight Russia’s occupation

Zla Mavka is a grassroots network of Ukrainian women operating under occupation. Named after mythical Ukrainian forest spirits known for their wild and mysterious nature, the Mavkas represent a nonviolent resistance movement

Zla-Mavka-le-donne-ucraine-resistono-all-occupazione-russa-1

Melitopol, Ukraine - photo Zla Mavka

In a modest kitchen in occupied Melitopol, Ukraine, a small group of women met in early 2023 to discuss a question that had come to dominate life in their city: how to resist.

Melitopol, a strategic city in southeastern Ukraine, had been under Russian military occupation for nearly a year by then. With Ukrainian flags torn down, pro-Kremlin authorities installed and media replaced by Russian state television, everyday life was becoming unrecognizable. But in that quiet meeting, a form of resistance began to take shape, involving women and non-violence.

That meeting led to the formation of Zla Mavka (Angry Mavkas or Angry Fairies), a grassroots network of Ukrainian women operating under occupation. Named after mythical Ukrainian forest spirits known for their wild and mysterious nature, the Mavkas represent a nonviolent resistance movement. Their aim is to preserve Ukrainian identity, culture and morale in a city where the occupiers want to erase them.

The City Under Occupation

Melitopol, a city of roughly 150,000 residents before the Russian full-scale war, sits at an important junction in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, southern Ukraine. It links Crimea, a peninsula that Russia occupied back in 2014, with the eastern regions of Ukraine, which have also been under the Russian control.

When Russian troops swept into the south in the opening weeks of the full-scale invasion that began on 24 February, 2022, Melitopol was quickly occupied. By 1 March, the Russian military had established control of the city, replacing local government officials with pro-Russian administrators.

From the outset, the occupation was marked by repression. Ukrainian-language signs were removed, protests were suppressed and dozens of residents – including journalists, activists and civil servants – were detained or disappeared. Russian forces introduced their own school curricula, broadcast Kremlin-controlled media and began issuing Russian passports to encourage “integration” – the locals had to become Russian citizens, otherwise they faced severe consequences from the occupying authorities.

Despite these efforts, many residents refused to adapt. Civil resistance – though often quiet and invisible – persisted, and in some cases, intensified. This was the case with Angry Mavkas.

This movement is not a typical undercover initiative, meaning that it does not involve soldiers or militants, and it focuses on non-violent resident. The movement unites women, many of whom are mothers or caregivers, and chose to remain in their city even as others fled. Their resistance takes the form of underground newspapers, symbolic protest actions and the distribution of factual information to combat Russian disinformation.

“The Russians expect passivity”, says the group’s anonymous founder, “they believe that occupation will become normal over time. We are here to make sure it never feels normal”.

Their underground newspaper is a central pillar of their work. It offers updates about the war, reminders of Ukrainian national holidays and short texts on history and identity. It is printed discreetly and hand-distributed – often left in mailboxes, on benches or inside apartment buildings. The goal is to reach people, especially those who do not have access to the Internet or depend on Russian-controlled television – often the elderly.

“People who only watch Russian TV start to believe what they hear”, explains the founder. “Our newspaper is meant to interrupt that and remind people that Ukraine has not disappeared.”

Another tactic is that of symbolic protest. The group has distributed fake Russian rubles with anti-war messages, placed pumpkins at the doors of well-known collaborators and painted small Ukrainian flags in alleyways and on electricity poles. These acts are often dismissed as mere pranks by occupying forces, but they carry significant meaning for locals. They signal that resistance is still alive and that Ukraine is not forgotten.

Risk and Surveillance

Operating under occupation is dangerous. Russian forces in Melitopol have carried out raids on suspected resistance members, detained civilians for social media posts and forced detainees to record public “confession” videos in which they denounce their actions. Detainees are often transferred to Crimea or Russia, where legal protections are minimal.

The Mavkas are aware of the risks.

“It only takes one mistake”, admits the founder. “That could be leaving your phone unsecured, trusting the wrong person or being in the wrong place when a patrol passes by”.

To minimize risk, the group operates using strict security protocols. Communication is limited, members use pseudonyms and activities are compartmentalized. Nobody knows everything. So far, the group has avoided arrests, which they attribute to discipline and constant vigilance.

“We live with fear”, says one member. “But fear does not have to mean silence”.

Members of Angry Mavkas are driven by a range of motivations. Some have lost family members in the war. Others were involved in civil society before the invasion. For many, the motivation is simpler: a refusal to accept the occupation of their city and the destruction of their national identity.

The group has expanded beyond Melitopol, with small cells now operating in other occupied areas of southern Ukraine, including parts of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts as well as Crimean Peninsula. Each group works independently to reduce exposure. While they share general goals, coordination is limited and indirect.

One of the group’s most personal projects is “The Mavka Diaries”, a collection of anonymous testimonies written by women living under occupation. These stories – published through secure online channels and in limited edition – document daily life, from navigating Russian checkpoints to the psychological effects of isolation. The diaries have been shared with Ukrainian media and international human rights organizations, providing insight into life behind enemy lines.

“People outside the occupation zone often ask us basic questions: ‘Do you have electricity? Is there food?’”, says the founder. “These diaries are a way to show that we are not just surviving. We are resisting”.

The work of Angry Mavkas is part of a larger pattern of civil resistance across occupied Ukraine. In the early days of the invasion, mass protests broke out in cities like Kherson, Berdiansk and Melitopol. After the repression of these protests, resistance became more covert: small groups, coded message and underground networks working to keep the idea of Ukraine alive.

The Ukrainian government has acknowledged the role of local resistance, with President Volodymyr Zelenskyy repeatedly praising those who “continue to fight” in silence. These groups are not formally part of the Ukrainian military, but are seen as a vital component of the country’s broader defense.

As the full-scale war enters its fourth year, Melitopol remains under Russian control, though it is frequently cited by Ukrainian military analysts as a critical target for future operations. Located on the so-called “land bridge” between Russia and Crimea, the city’s liberation would strike a strategic blow to Russian logistics.

Until that happens, the residents who resist remain hopeful.

“Our city is occupied”, says the founder, “but not our identity. That is what we are protecting”.

Tag: Donne 2