Integration challenges of Ukrainian refugees in Italy

Ukrainian refugees in Italy face mounting challenges as early solidarity fades. Language hurdles, job insecurity, and rising social tensions reveal the gap between initial support and long-term integration

Rifugiati-ucraini-in-Italia-le-sfide-dell-integrazione

© Maryna Svitlychna

For many Ukrainian refugees, arriving in Italy brought a sense of safety – but also marked the beginning of a long and uncertain journey. “Life feels like it’s on pause,” says Polina, describing constant anxiety for those back home. Diana, whose city was destroyed, adds: “You have to grab every opportunity, because there’s no plan B.” Even for those rebuilding, the future remains unclear. “I still have to figure out who I’ll become after this war,” Tetiana reflects. As weeks turned into months, and months into years, another challenge emerged: how to belong?

Barriers to integration in Italy

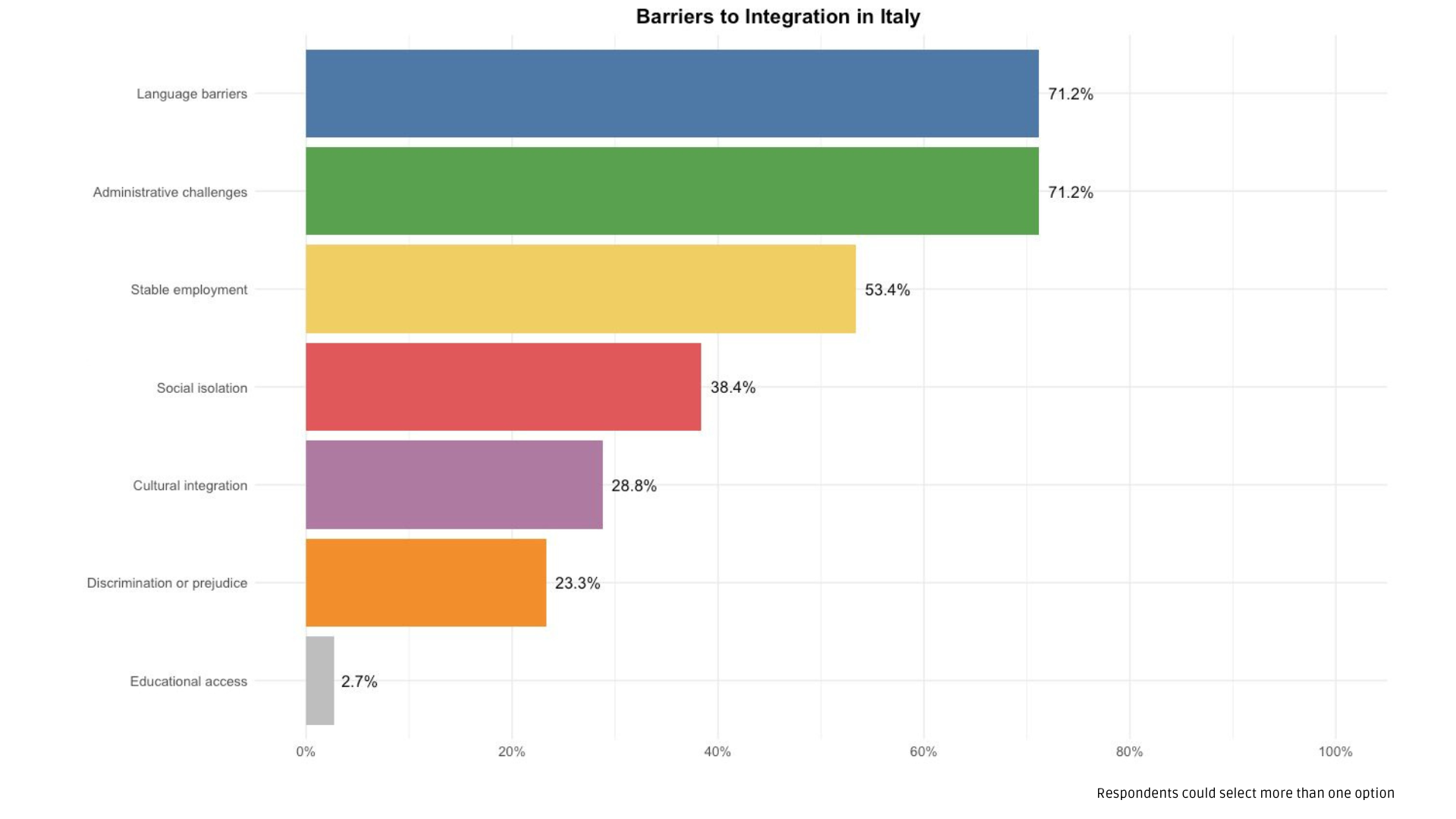

To better understand the main challenges faced by Ukrainian refugees in Italy, we conducted a survey and several interviews to explore their experiences with public authorities, institutions, and Italian society. The results showed that, while Italy provided immediate protection and basic support to Ukrainians fleeing war, many say deeper integration remains difficult.

According to the survey, 71.2% of respondents identified both language and bureaucratic confusion as major obstacles, followed by 53.4% reporting difficulty finding stable employment, and 38.4% experiencing social isolation.

As Tetiana notes, “language courses and support services exist, but people usually learn about them by chance. Especially in small towns, it’s hard to know where to go.” Language remains a key concern not just for communication, but for employment and autonomy.

Italian bureaucracy poses another challenge. “When they announced the need to renew stay permits, there was a lot of confusion at the Questura (central police station),” recalls Vladyslava. “People lost jobs, healthcare, or couldn’t travel for studies because the state didn’t clearly communicate procedures.” Daria adds: “Competent social workers and support services could make a huge difference, especially for newly arrived refugees struggling with changing procedures.”

Beyond practical aid, emotional safety and solidarity are also important. Several interviewees noted a growing gap between Italy’s initial welcome and its current stance – particularly as Russian propaganda spreads in some public spaces. “It’s important to ensure constant access to reliable information to counter pro-Russian narratives,” says Tetiana. She stresses the need to explain why supporting Ukraine matters – not just now, but until the war ends since Ukrainians fight not only for themselves, but shared European values: freedom, democracy, and dignity. “People fleeing war are forced to justify themselves or explain the obvious, which shouldn’t be the case.”

Some also highlight limited social inclusion, especially when refugees are seen as outsiders. “Italy isn’t ready to be a multicultural country,” says Sofiia. “Some topics are hard to discuss in Italian, which isn’t my native language. It would help if Italians accepted this and treated us without prejudice.” She stresses the need to counter the idea that “migrants are second-class people,” noting that they can contribute positively and aren’t here to undermine Italian culture. Integration isn’t one-sided. While many are learning the language and adapting, they need a system that truly supports inclusion.

Education and work opportunities

For some Ukrainian refugees, education has offered a temporary anchor in Italy, but long-term settlement remains uncertain. Diana highlights the importance of education, having completed a degree in applied linguistics with university support. Yet, she emphasizes a sharp divide in the job market: “Basic jobs like working in a hotel or as a waiter are possible if you speak Italian, but more qualified positions are much harder to access.”

This experience is common: 31.4% of survey respondents found work in their field, while 68.6% worked underpaid jobs, often being overqualified. The mismatch between qualifications and opportunities is a shared concern. “I’m studying English and German linguistics, but I don’t think my degree will help me find work here,” says Vladyslava. “It’s hard for foreigners to get jobs in Italy, especially in the humanities.”

Yevheniia, a psychology professor in Ukraine, also notes that diploma recognition and better job opportunities would significantly influence her decision to stay: “I haven’t found a job, but it would definitely help.” Overall, 24.7% of survey respondents are unemployed and 17.8% are inactive, mostly students or retirees. For many, meaningful, stable work is not just an economic need but a precondition for real integration.

Shifting attitudes in Italian society

Every Ukrainian interviewed noted a shift in attitudes within Italian society. Polina observes mixed reactions: “many sincerely support Ukraine, but there is also fatigue and indifference.” Diana recalls that the beginning of the war was marked by demonstrations and campaigns, but “comparatively nothing is happening” today, and some Italians even believe the war is over.

Apart from that, Vladyslava adds that some now blame Ukrainians, “accusing of not having surrendered the territories yet” and, thus, letting the war continue, forgetting that “it was Russia that attacked and all the blame should lie solely with it.”

It is important that the media continues covering the Russo-Ukrainian war. Without immediate threats and amid ongoing disinformation, “people think the situation in Ukraine does not concern them directly, although the war on this continent cannot but affect the overall security and stability of Europe,” says Tetiana.

As some show indifference or even hostility, calling for reduced support, refugees may feel unwelcome, weakening their desire to integrate. In this context, Polina points out that people with neutral or pro-Russian positions are anywhere, so they don’t affect her decision to stay in Italy. More crucial, she says, is the Italian authorities’ stance, as it translates into providing humanitarian aid, enforcing sanctions on Russia, contributing to Ukraine’s military efforts, and navigating complex diplomatic challenges.

Discrimination is still a reality

While many Ukrainian refugees in Italy feel supported by the local society, 9.6% of respondents perceive Italians as holding negative attitudes toward Ukrainians, and 38.4% say they have personally encountered some form of discrimination. Although these cases are not widespread, they reveal important challenges experienced by some refugees.

Some describe being humiliated for their Italian language skills, either because of their grammar or their accent. These linguistic problems foster prejudices that make Ukrainians feel sometimes treated as intellectually inferior.

Prejudice is also fueled by pro-Russian narratives. Several respondents report being told that Ukrainians and Russians are the same people, forcing them to repeatedly explain the distinction. Moreover, hostile comments and slogans, such as “Glory to Russia,” have been directed at some Ukrainians, alongside negative remarks about Ukrainian society during the war.

Institutional barriers have also been reported by some refugees that faced difficulties renting housing without local contacts, and cases where public officials refused to speak at all when asked to communicate in English. One respondent also shared that officials told them, “If you don’t like something in Italy, go back to Ukraine”.

Social rejection and hostility also affect a smaller portion of the community. Some report that certain Italians express frustration openly, telling them to “go back home.” Economic scapegoating occurs as well, with complaints such as “We have to pay a lot for gas now because of you,” blaming Ukrainians for broader hardships.

In education, some Ukrainian children face bullying and negative treatment from teachers, making their adjustment and sense of safety more difficult. Employment discrimination exists too. One particularly serious case involved a refugee being refused a job and told that as a Ukrainian, she “could only be a prostitute.”

Though these attitudes are not the norm, these testimonies highlight that discrimination still exists and affects the integration experiences.

This article was produced as part of “MigraVoice: Migrant Voices Matter in the European Media”, an editorial project supported by the European Union. The positions contained in this article are the expression of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the positions of the European Union.

Tag: MigraVoice | Refugees and IDPs

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Integration challenges of Ukrainian refugees in Italy

Ukrainian refugees in Italy face mounting challenges as early solidarity fades. Language hurdles, job insecurity, and rising social tensions reveal the gap between initial support and long-term integration

Rifugiati-ucraini-in-Italia-le-sfide-dell-integrazione

© Maryna Svitlychna

For many Ukrainian refugees, arriving in Italy brought a sense of safety – but also marked the beginning of a long and uncertain journey. “Life feels like it’s on pause,” says Polina, describing constant anxiety for those back home. Diana, whose city was destroyed, adds: “You have to grab every opportunity, because there’s no plan B.” Even for those rebuilding, the future remains unclear. “I still have to figure out who I’ll become after this war,” Tetiana reflects. As weeks turned into months, and months into years, another challenge emerged: how to belong?

Barriers to integration in Italy

To better understand the main challenges faced by Ukrainian refugees in Italy, we conducted a survey and several interviews to explore their experiences with public authorities, institutions, and Italian society. The results showed that, while Italy provided immediate protection and basic support to Ukrainians fleeing war, many say deeper integration remains difficult.

According to the survey, 71.2% of respondents identified both language and bureaucratic confusion as major obstacles, followed by 53.4% reporting difficulty finding stable employment, and 38.4% experiencing social isolation.

As Tetiana notes, “language courses and support services exist, but people usually learn about them by chance. Especially in small towns, it’s hard to know where to go.” Language remains a key concern not just for communication, but for employment and autonomy.

Italian bureaucracy poses another challenge. “When they announced the need to renew stay permits, there was a lot of confusion at the Questura (central police station),” recalls Vladyslava. “People lost jobs, healthcare, or couldn’t travel for studies because the state didn’t clearly communicate procedures.” Daria adds: “Competent social workers and support services could make a huge difference, especially for newly arrived refugees struggling with changing procedures.”

Beyond practical aid, emotional safety and solidarity are also important. Several interviewees noted a growing gap between Italy’s initial welcome and its current stance – particularly as Russian propaganda spreads in some public spaces. “It’s important to ensure constant access to reliable information to counter pro-Russian narratives,” says Tetiana. She stresses the need to explain why supporting Ukraine matters – not just now, but until the war ends since Ukrainians fight not only for themselves, but shared European values: freedom, democracy, and dignity. “People fleeing war are forced to justify themselves or explain the obvious, which shouldn’t be the case.”

Some also highlight limited social inclusion, especially when refugees are seen as outsiders. “Italy isn’t ready to be a multicultural country,” says Sofiia. “Some topics are hard to discuss in Italian, which isn’t my native language. It would help if Italians accepted this and treated us without prejudice.” She stresses the need to counter the idea that “migrants are second-class people,” noting that they can contribute positively and aren’t here to undermine Italian culture. Integration isn’t one-sided. While many are learning the language and adapting, they need a system that truly supports inclusion.

Education and work opportunities

For some Ukrainian refugees, education has offered a temporary anchor in Italy, but long-term settlement remains uncertain. Diana highlights the importance of education, having completed a degree in applied linguistics with university support. Yet, she emphasizes a sharp divide in the job market: “Basic jobs like working in a hotel or as a waiter are possible if you speak Italian, but more qualified positions are much harder to access.”

This experience is common: 31.4% of survey respondents found work in their field, while 68.6% worked underpaid jobs, often being overqualified. The mismatch between qualifications and opportunities is a shared concern. “I’m studying English and German linguistics, but I don’t think my degree will help me find work here,” says Vladyslava. “It’s hard for foreigners to get jobs in Italy, especially in the humanities.”

Yevheniia, a psychology professor in Ukraine, also notes that diploma recognition and better job opportunities would significantly influence her decision to stay: “I haven’t found a job, but it would definitely help.” Overall, 24.7% of survey respondents are unemployed and 17.8% are inactive, mostly students or retirees. For many, meaningful, stable work is not just an economic need but a precondition for real integration.

Shifting attitudes in Italian society

Every Ukrainian interviewed noted a shift in attitudes within Italian society. Polina observes mixed reactions: “many sincerely support Ukraine, but there is also fatigue and indifference.” Diana recalls that the beginning of the war was marked by demonstrations and campaigns, but “comparatively nothing is happening” today, and some Italians even believe the war is over.

Apart from that, Vladyslava adds that some now blame Ukrainians, “accusing of not having surrendered the territories yet” and, thus, letting the war continue, forgetting that “it was Russia that attacked and all the blame should lie solely with it.”

It is important that the media continues covering the Russo-Ukrainian war. Without immediate threats and amid ongoing disinformation, “people think the situation in Ukraine does not concern them directly, although the war on this continent cannot but affect the overall security and stability of Europe,” says Tetiana.

As some show indifference or even hostility, calling for reduced support, refugees may feel unwelcome, weakening their desire to integrate. In this context, Polina points out that people with neutral or pro-Russian positions are anywhere, so they don’t affect her decision to stay in Italy. More crucial, she says, is the Italian authorities’ stance, as it translates into providing humanitarian aid, enforcing sanctions on Russia, contributing to Ukraine’s military efforts, and navigating complex diplomatic challenges.

Discrimination is still a reality

While many Ukrainian refugees in Italy feel supported by the local society, 9.6% of respondents perceive Italians as holding negative attitudes toward Ukrainians, and 38.4% say they have personally encountered some form of discrimination. Although these cases are not widespread, they reveal important challenges experienced by some refugees.

Some describe being humiliated for their Italian language skills, either because of their grammar or their accent. These linguistic problems foster prejudices that make Ukrainians feel sometimes treated as intellectually inferior.

Prejudice is also fueled by pro-Russian narratives. Several respondents report being told that Ukrainians and Russians are the same people, forcing them to repeatedly explain the distinction. Moreover, hostile comments and slogans, such as “Glory to Russia,” have been directed at some Ukrainians, alongside negative remarks about Ukrainian society during the war.

Institutional barriers have also been reported by some refugees that faced difficulties renting housing without local contacts, and cases where public officials refused to speak at all when asked to communicate in English. One respondent also shared that officials told them, “If you don’t like something in Italy, go back to Ukraine”.

Social rejection and hostility also affect a smaller portion of the community. Some report that certain Italians express frustration openly, telling them to “go back home.” Economic scapegoating occurs as well, with complaints such as “We have to pay a lot for gas now because of you,” blaming Ukrainians for broader hardships.

In education, some Ukrainian children face bullying and negative treatment from teachers, making their adjustment and sense of safety more difficult. Employment discrimination exists too. One particularly serious case involved a refugee being refused a job and told that as a Ukrainian, she “could only be a prostitute.”

Though these attitudes are not the norm, these testimonies highlight that discrimination still exists and affects the integration experiences.

This article was produced as part of “MigraVoice: Migrant Voices Matter in the European Media”, an editorial project supported by the European Union. The positions contained in this article are the expression of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the positions of the European Union.

Tag: MigraVoice | Refugees and IDPs