Between Two Worlds: The Dilemma for Ukrainian Refugees About Returning Home

Living a life as a refugee, far from home, but constantly thinking about their country. There are those who think of returning, those who have already returned and have had to adapt to a country at war, those who perhaps will never return and will remain divided between two worlds

Between-Two-Worlds-The-Dilemma-for-Ukrainian-Refugees-About-Returning-Home

© Maryna Svitlychna

When the Russo-Ukrainian war began in February 2022, many Ukrainians left their homes thinking it would only be for a few months – that the war would end quickly and they would return. But as time went on, it became clear that both the fighting and the displacement would last much longer, even as many continued to hope for a quick resolution. Three years later, 6.8 million Ukrainian refugees have been registered worldwide, with 163,630 granted temporary protection in Italy as of February 2025. Yet many Ukrainian refugees in Italy now find themselves torn between returning home and building a new life abroad.

Choosing Italy and Finding a New Normal

I left my home city, Kharkiv, in mid-March 2022 with my mother. We didn’t even know if we’d make it to western Ukraine, but once we got there, we had three days to rest and decide. We were choosing between Italy and Germany – two places I’ve lived in before, and decided on Trento, Italy, where I studied as an exchange student. The choice was quick. First, I already knew the region and some people, which made it less stressful. Second, even though I knew Germany offered a stronger economy and job market, at that moment, I needed the colors and sunshine of Italy for my mental ‘well-being’. Although I was only 23 at the time, I had to grow up very fast as I was the one who knew a bit of the language and had to handle all the bureaucracy.

Each of us had our own reasons for ending up in Italy – some driven by choice, others by circumstance. "I wouldn’t say I chose Italy – it was Italy that chose me," says Diana who had just returned to Ukraine after an Erasmus+ ICM semester in Trento when the war began. “The University of Trento reached out and offered support, both moral and financial, to students like me who had just returned to Ukraine and suddenly found themselves in danger. That’s why I came back to Italy. It wasn’t a decision made from comfort, but from necessity.”

Despite the opportunity to be in a safe place where there was no bombing and nothing threatening life, many of us felt depressed and lost. “We felt safe physically, but not morally and financially,” continues Diana, whose family and friends stayed in Ukraine. There were times when it was really hard – “you wake up, read the news about shelling, tragedies, brutal killings – and then have to go to classes, trying not to show how you actually feel”, adds Tetiana, another Ukrainian refugee in Trento.

Also for me there were tough moments, especially when the emotional weight of the war clashed with daily routines. I remember watching a segment of The Day After during history class, the film that once shocked Reagan into opposing nuclear weapons, while nuclear threats in Ukraine were growing. My classmates calmly analyzed Cold War policy, but I sat frozen, barely holding back tears, thinking only of my home, my relatives, and my friends.

What was helping us to stay strong was the idea that we are not in the worst situation. The support from Italian society at the beginning of the war also played an important role for Ukrainian refugees – it was important to feel solidarity and intentions to help.

The Dilemma of Return

Since arriving in Italy, there have been some moments for each of us that have made us reconsider the idea of returning to Ukraine. Diana, who used to live in Bakhmut, a city in Donetsk region that is entirely destroyed, reflects that the difference in mentality sometimes makes her feel deeply misunderstood. “You feel like a guest here, and you know you’ll never truly feel this country as your own,” she says.

Moments like that sparked a longing to return to Ukraine, but for her, the idea remains completely out of reach because there is simply nowhere to return to. She envisions her future abroad, possibly not in Italy but somewhere in Europe, where she hopes to build a stable life, find work, and integrate.

As she explains, coming back to Ukraine and starting life over again would be even harder for her than continuing to build what she has already started in Europe over these three years. Today, housing prices are too high in Ukraine, and salaries are insufficient to cover the cost of living, including rent, food, healthcare, and basically everything else. At most, she imagines visits after the war, only to reconnect with her culture.

For Tetiana, however, the ongoing destruction brings a different kind of reflection. “The more I witness the devastation of my country, the more painful it becomes,” she says, “but it also makes me reflect on my place in rebuilding it”. As a Ukrainian citizen, she feels responsible for the future of Ukraine and for contributing to its recovery and nation-building. However, she avoids making firm projections about the future as thinking too far ahead frightens her, and her decisions to stay in Italy will be influenced by how her personal life unfolds. A lot of uncertainty remains for her on how often she will be able to see her parents or what she can do as a conscious citizen.

Vladyslava, a Ukrainian refugee from the Odesa region, faces a similar dilemma. She considers returning to Ukraine for at least a short time after finishing her studies in Italy because her family is there and she believes there will be many job opportunities after the war, in addition to a comfortable life in terms of healthcare system, housing, food, culture, and community. However, her personal relationships have formed abroad.

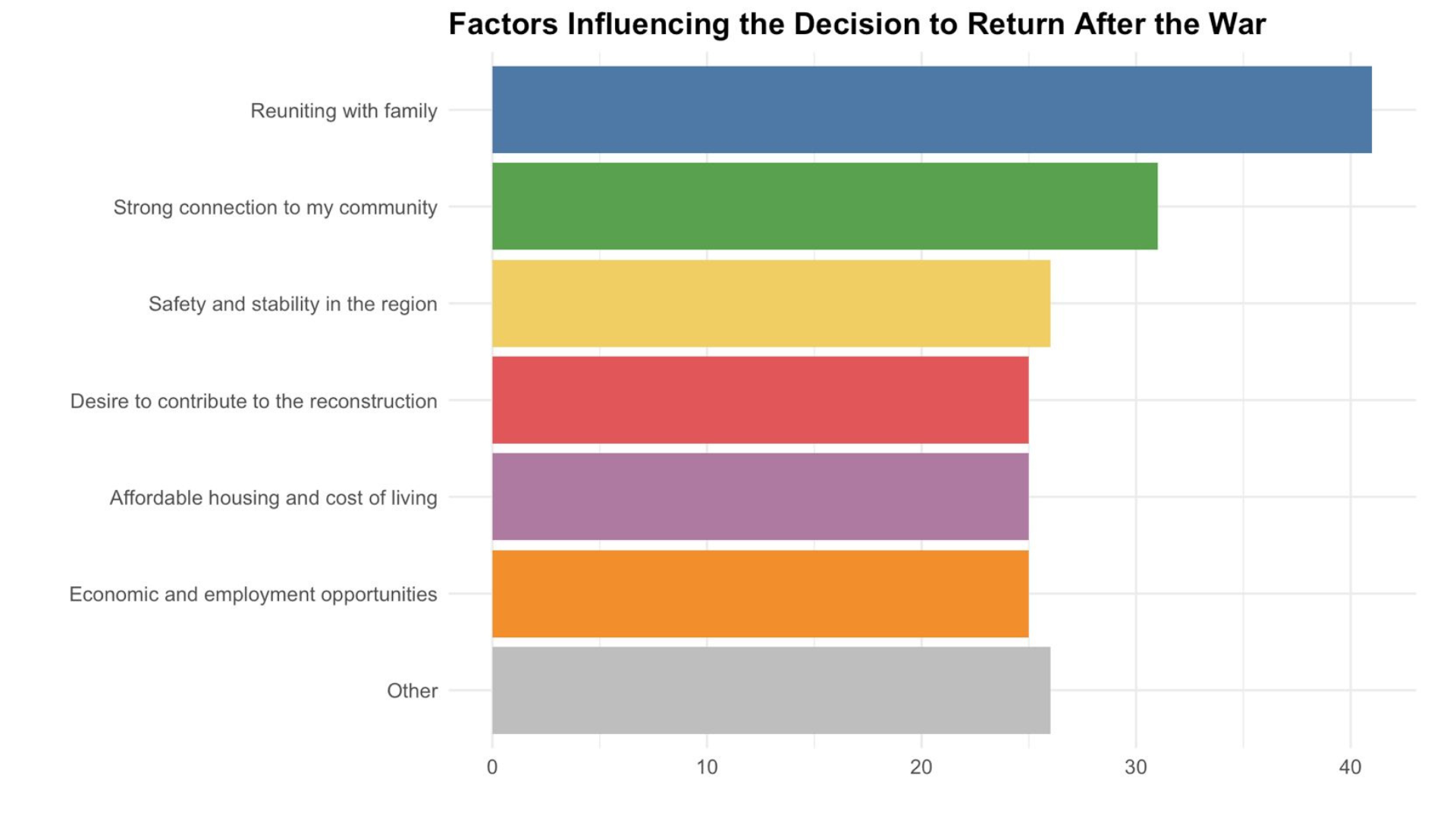

They are not the only ones for whom family and connection to the community are one of the most important factors for returning to Ukraine after the war. Every second Ukrainian surveyed indicates a desire for reunification, although it is always a group of factors, both negative and positive, that shape the final decision.

As such, safety and stability in the region, which implies not only security threats from Russia and the struggling economy in Ukraine, but also broader geopolitical affairs negatively influence people’s decisions to return. Today even Ukrainian children closely follow world events and understand how foreign policy directly affects their future.

Diana fears that a change in U.S. leadership could shift the focus away from supporting Ukraine toward negotiating a quick resolution that primarily serves American and Russian interests. “Ukraine’s losses – territories, lives, resources – don’t seem to matter. The U.S. just wants to end the war on its terms,” she said. Such geopolitical maneuvering could result in Ukraine being pressured into an unfavorable agreement that compromises its sovereignty and long-term security.

Tetiana, too, emphasized how foreign policies, especially from some EU countries, have a direct and damaging effect on the war’s progression. She pointed to countries that continue to cooperate with Russia or undermine sanctions. “As long as Russia remains a partner to some, it has access to resources that keep the war going,” she explained. This cooperation not only prolongs the conflict but also erodes Ukraine’s ability to recover economically and defend itself effectively. This makes it harder for Ukrainians to imagine a secure and stable future as for many, the question of return is not just about personal circumstances, it is about whether Ukraine will be a safe and sovereign state at all.

Other factors influencing the decision to return now included legal and administrative barriers, such as military restrictions, and termination of temporary protection, but also language-based discrimination, psychological impacts of the war, integration and social ties in host countries, and the absence of a home or support network to return to after the war ends.

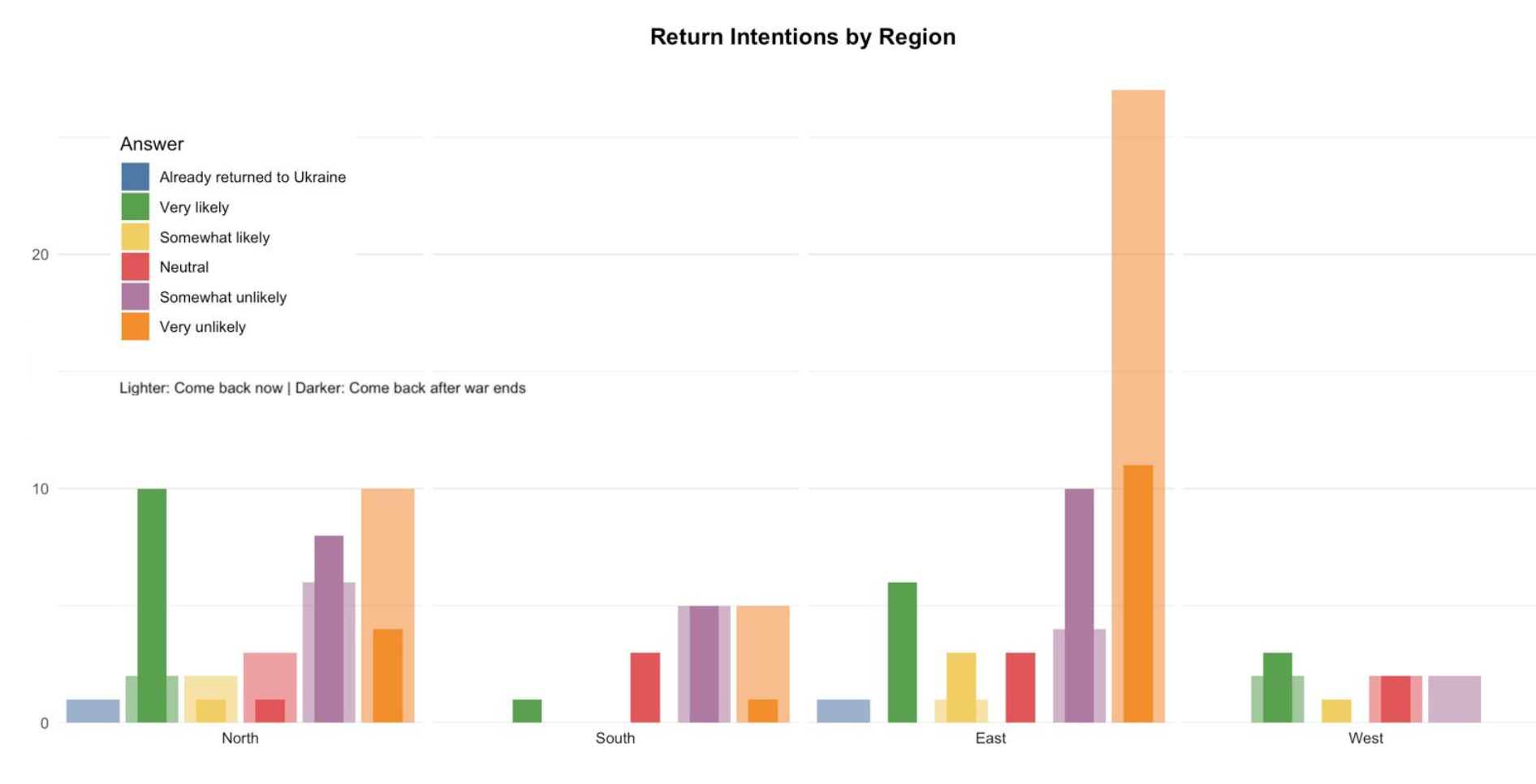

While the desire for return might be strong, the timing and likelihood also vary significantly by region of origin. People from the East and South of Ukraine are least likely to return, especially before the war ends. These regions have endured some of the most intense fighting, prolonged occupations, and widespread destruction, making the idea of return particularly difficult and uncertain.

Stories of Return: Adapting to a Changed Homeland

Although the vast majority of Ukrainians are currently not inclined to return, some have already taken that step. The reason is simple: “being home is better no matter what,” say Maryna and Shamsiiia, who have returned to Kyiv and Kharkiv, respectively. As mothers of small children, they share how difficult it was to cope alone, without their families and husbands by their side.

The second most important factor was the uncertainty about the war – “not knowing when it would end, together with social challenges, from finding housing to the difficulty of socialisation in a completely different environment,” continues Shamsiiia.

Both of them have reported that the most challenges after returning to Ukraine have been adaptation to Ukraine in war, exhaustion due to the lack of sleep and constant anxiety due to constant air alerts, together with power and heating outages caused by hostilities – something that Ukrainians have to live through on a daily basis.

It took Shamsiiia 6 months to adapt and realise where she is, how she should live and get ready to go to work. She returned to the frontline city, which is shelled every day and has a completely different appearance, unlike the one she remembered in peacetime. “The rules of residence in the city have changed and you have to know how to behave during an air alert, when you can go outside, know the map of shelters,” she says.

The desire to go abroad again remains a constant for her. “Every day, when something happens, people die, the place you know is targeted, it makes you doubt whether you are doing the right thing by staying at home,” explains Shamsiiia. “But then everything calms down, and you calm down with it – it is a certain rhythm that you get used to.”

To understand this, you just need to be in Kharkiv, because it’s a completely different life now. Shamsiiia says that her mother, who stays abroad, often tells she wants to come back. But when she describes what she wants to return to, she describes that peaceful life we used to have.

The one no longer exists. “Yes, people go to work, take public transport, go to cafes but it all happens differently now.” However, after a period of adaptation, a certain stability emerged for Shamsiiia, certain things started to anchor her, and it became much harder to break away. Thus, she tries to normalize her life and bring it back to things that ground her.

Disclaimer: This survey includes 73 respondents and is not statistically representative. The results illustrate sample trends but should not be seen as conclusive or generalizable due to the small, potentially biased sample.

This article was produced as part of “MigraVoice: Migrant Voices Matter in the European Media”, an editorial project supported by the European Union. The positions contained in this article are the expression of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the positions of the European Union.

Tag: MigraVoice | Refugees and IDPs

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Between Two Worlds: The Dilemma for Ukrainian Refugees About Returning Home

Living a life as a refugee, far from home, but constantly thinking about their country. There are those who think of returning, those who have already returned and have had to adapt to a country at war, those who perhaps will never return and will remain divided between two worlds

Between-Two-Worlds-The-Dilemma-for-Ukrainian-Refugees-About-Returning-Home

© Maryna Svitlychna

When the Russo-Ukrainian war began in February 2022, many Ukrainians left their homes thinking it would only be for a few months – that the war would end quickly and they would return. But as time went on, it became clear that both the fighting and the displacement would last much longer, even as many continued to hope for a quick resolution. Three years later, 6.8 million Ukrainian refugees have been registered worldwide, with 163,630 granted temporary protection in Italy as of February 2025. Yet many Ukrainian refugees in Italy now find themselves torn between returning home and building a new life abroad.

Choosing Italy and Finding a New Normal

I left my home city, Kharkiv, in mid-March 2022 with my mother. We didn’t even know if we’d make it to western Ukraine, but once we got there, we had three days to rest and decide. We were choosing between Italy and Germany – two places I’ve lived in before, and decided on Trento, Italy, where I studied as an exchange student. The choice was quick. First, I already knew the region and some people, which made it less stressful. Second, even though I knew Germany offered a stronger economy and job market, at that moment, I needed the colors and sunshine of Italy for my mental ‘well-being’. Although I was only 23 at the time, I had to grow up very fast as I was the one who knew a bit of the language and had to handle all the bureaucracy.

Each of us had our own reasons for ending up in Italy – some driven by choice, others by circumstance. "I wouldn’t say I chose Italy – it was Italy that chose me," says Diana who had just returned to Ukraine after an Erasmus+ ICM semester in Trento when the war began. “The University of Trento reached out and offered support, both moral and financial, to students like me who had just returned to Ukraine and suddenly found themselves in danger. That’s why I came back to Italy. It wasn’t a decision made from comfort, but from necessity.”

Despite the opportunity to be in a safe place where there was no bombing and nothing threatening life, many of us felt depressed and lost. “We felt safe physically, but not morally and financially,” continues Diana, whose family and friends stayed in Ukraine. There were times when it was really hard – “you wake up, read the news about shelling, tragedies, brutal killings – and then have to go to classes, trying not to show how you actually feel”, adds Tetiana, another Ukrainian refugee in Trento.

Also for me there were tough moments, especially when the emotional weight of the war clashed with daily routines. I remember watching a segment of The Day After during history class, the film that once shocked Reagan into opposing nuclear weapons, while nuclear threats in Ukraine were growing. My classmates calmly analyzed Cold War policy, but I sat frozen, barely holding back tears, thinking only of my home, my relatives, and my friends.

What was helping us to stay strong was the idea that we are not in the worst situation. The support from Italian society at the beginning of the war also played an important role for Ukrainian refugees – it was important to feel solidarity and intentions to help.

The Dilemma of Return

Since arriving in Italy, there have been some moments for each of us that have made us reconsider the idea of returning to Ukraine. Diana, who used to live in Bakhmut, a city in Donetsk region that is entirely destroyed, reflects that the difference in mentality sometimes makes her feel deeply misunderstood. “You feel like a guest here, and you know you’ll never truly feel this country as your own,” she says.

Moments like that sparked a longing to return to Ukraine, but for her, the idea remains completely out of reach because there is simply nowhere to return to. She envisions her future abroad, possibly not in Italy but somewhere in Europe, where she hopes to build a stable life, find work, and integrate.

As she explains, coming back to Ukraine and starting life over again would be even harder for her than continuing to build what she has already started in Europe over these three years. Today, housing prices are too high in Ukraine, and salaries are insufficient to cover the cost of living, including rent, food, healthcare, and basically everything else. At most, she imagines visits after the war, only to reconnect with her culture.

For Tetiana, however, the ongoing destruction brings a different kind of reflection. “The more I witness the devastation of my country, the more painful it becomes,” she says, “but it also makes me reflect on my place in rebuilding it”. As a Ukrainian citizen, she feels responsible for the future of Ukraine and for contributing to its recovery and nation-building. However, she avoids making firm projections about the future as thinking too far ahead frightens her, and her decisions to stay in Italy will be influenced by how her personal life unfolds. A lot of uncertainty remains for her on how often she will be able to see her parents or what she can do as a conscious citizen.

Vladyslava, a Ukrainian refugee from the Odesa region, faces a similar dilemma. She considers returning to Ukraine for at least a short time after finishing her studies in Italy because her family is there and she believes there will be many job opportunities after the war, in addition to a comfortable life in terms of healthcare system, housing, food, culture, and community. However, her personal relationships have formed abroad.

They are not the only ones for whom family and connection to the community are one of the most important factors for returning to Ukraine after the war. Every second Ukrainian surveyed indicates a desire for reunification, although it is always a group of factors, both negative and positive, that shape the final decision.

As such, safety and stability in the region, which implies not only security threats from Russia and the struggling economy in Ukraine, but also broader geopolitical affairs negatively influence people’s decisions to return. Today even Ukrainian children closely follow world events and understand how foreign policy directly affects their future.

Diana fears that a change in U.S. leadership could shift the focus away from supporting Ukraine toward negotiating a quick resolution that primarily serves American and Russian interests. “Ukraine’s losses – territories, lives, resources – don’t seem to matter. The U.S. just wants to end the war on its terms,” she said. Such geopolitical maneuvering could result in Ukraine being pressured into an unfavorable agreement that compromises its sovereignty and long-term security.

Tetiana, too, emphasized how foreign policies, especially from some EU countries, have a direct and damaging effect on the war’s progression. She pointed to countries that continue to cooperate with Russia or undermine sanctions. “As long as Russia remains a partner to some, it has access to resources that keep the war going,” she explained. This cooperation not only prolongs the conflict but also erodes Ukraine’s ability to recover economically and defend itself effectively. This makes it harder for Ukrainians to imagine a secure and stable future as for many, the question of return is not just about personal circumstances, it is about whether Ukraine will be a safe and sovereign state at all.

Other factors influencing the decision to return now included legal and administrative barriers, such as military restrictions, and termination of temporary protection, but also language-based discrimination, psychological impacts of the war, integration and social ties in host countries, and the absence of a home or support network to return to after the war ends.

While the desire for return might be strong, the timing and likelihood also vary significantly by region of origin. People from the East and South of Ukraine are least likely to return, especially before the war ends. These regions have endured some of the most intense fighting, prolonged occupations, and widespread destruction, making the idea of return particularly difficult and uncertain.

Stories of Return: Adapting to a Changed Homeland

Although the vast majority of Ukrainians are currently not inclined to return, some have already taken that step. The reason is simple: “being home is better no matter what,” say Maryna and Shamsiiia, who have returned to Kyiv and Kharkiv, respectively. As mothers of small children, they share how difficult it was to cope alone, without their families and husbands by their side.

The second most important factor was the uncertainty about the war – “not knowing when it would end, together with social challenges, from finding housing to the difficulty of socialisation in a completely different environment,” continues Shamsiiia.

Both of them have reported that the most challenges after returning to Ukraine have been adaptation to Ukraine in war, exhaustion due to the lack of sleep and constant anxiety due to constant air alerts, together with power and heating outages caused by hostilities – something that Ukrainians have to live through on a daily basis.

It took Shamsiiia 6 months to adapt and realise where she is, how she should live and get ready to go to work. She returned to the frontline city, which is shelled every day and has a completely different appearance, unlike the one she remembered in peacetime. “The rules of residence in the city have changed and you have to know how to behave during an air alert, when you can go outside, know the map of shelters,” she says.

The desire to go abroad again remains a constant for her. “Every day, when something happens, people die, the place you know is targeted, it makes you doubt whether you are doing the right thing by staying at home,” explains Shamsiiia. “But then everything calms down, and you calm down with it – it is a certain rhythm that you get used to.”

To understand this, you just need to be in Kharkiv, because it’s a completely different life now. Shamsiiia says that her mother, who stays abroad, often tells she wants to come back. But when she describes what she wants to return to, she describes that peaceful life we used to have.

The one no longer exists. “Yes, people go to work, take public transport, go to cafes but it all happens differently now.” However, after a period of adaptation, a certain stability emerged for Shamsiiia, certain things started to anchor her, and it became much harder to break away. Thus, she tries to normalize her life and bring it back to things that ground her.

Disclaimer: This survey includes 73 respondents and is not statistically representative. The results illustrate sample trends but should not be seen as conclusive or generalizable due to the small, potentially biased sample.

This article was produced as part of “MigraVoice: Migrant Voices Matter in the European Media”, an editorial project supported by the European Union. The positions contained in this article are the expression of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the positions of the European Union.

Tag: MigraVoice | Refugees and IDPs