Strait of Otranto: Italy vetoes the proposed protected reserve

FAO is negotiating a series of new measures to reduce the devastating impact of trawling and make fishing in the Adriatic Sea sustainable. The institution of the Mediterranean’s largest protected reserve was part of the package, but the Italian government has blocked it

Strait-of-Otranto-Italy-vetoes-the-proposed-protected-reserve

(This article was originally published by MobileReporter/VoxEurop on November 4, 2019)

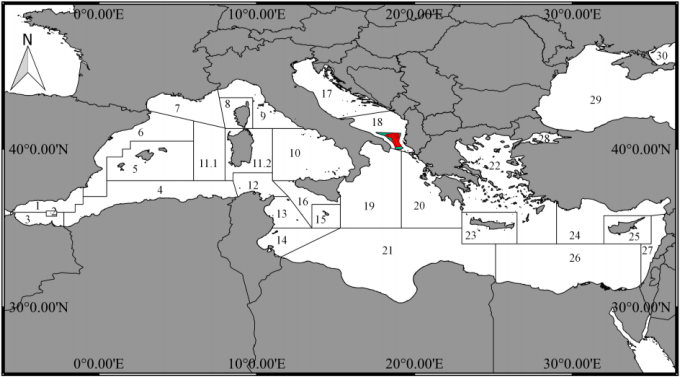

At their annual meeting held on 4-8 November in Athens, the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM), a special body of the FAO uniting 24 countries north and south of the Mediterranean, is supposed to approve a new action plan for the Adriatic Sea. The document is still confidential, but our investigators have managed to take a peek. The aim of the plan is to combat the alarming fall in demersal fish stocks in the Adriatic. This sea, according to a 2018 study , is the most exploited in the world when it comes to deep sea trawling. According to FAO data , as a proportion of the whole Mediterranean basin, it is also one of the most productive fishing areas: from its waters a little under 200,000 tonnes of fish are landed annually, half of which by Italy.

The package on the negotiation table in Athens includes the following principal measures: reduction of fishing days, a two month ban each year near the coast, a ban on trawling within six nautical miles, a reduction of the minimum fishable size and therefore of net mesh size, and compulsory geolocation systems on all fishing vessels larger than twelve metres to facilitate coast guard checks.

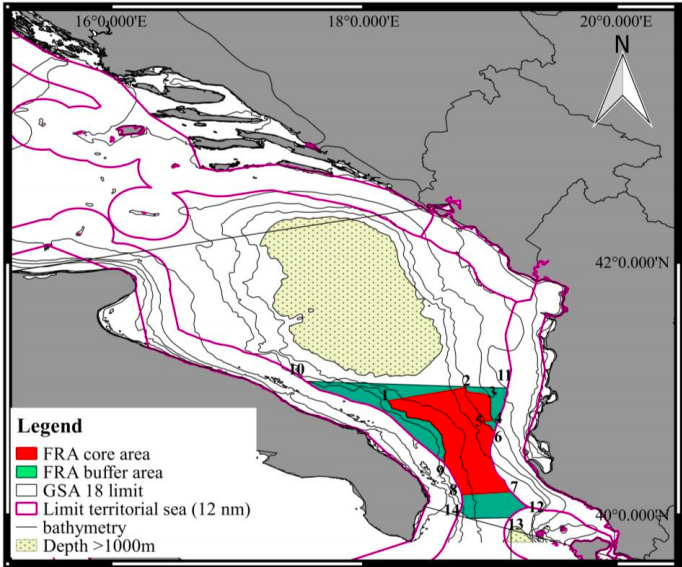

The initial draft of the EU plan included the creation of the largest protected reserve in the Mediterranean: an area of 2,800 square kilometres (twice the area of Rome) located in the international waters of the Strait of Otranto, between Italy and Albania, twelve nautical miles (22 kilometres) from the Apulian coast.

The area is rich in the most threatened and profitable species: deep-water rose shrimp and hake. According to a 2011 study , more than forty percent of the hake which lands on Italian dining tables comes from the Adriatic. Catches of hake in the entire Adriatic are twice its sustainability level, according to a 2017 study by the EU’s Scientific Committee for Fisheries.

Nevertheless, the Italian government has blocked the establishment of this marine sanctuary, judging it rushed, despite the restriction on trawling nets in its waters, agreed with the cooperatives and ship-owners of Monopoli and Mola di Bari. These are the two principal fleets operating in the area, with about forty vessels, docked in the harbours of Brindisi and Otranto respectively, and flanked by other vessels in Salento. The Italian veto also affects the smaller reserve in Bari Canyon.

The need for repopulation of fish stocks

The data shows that overfishing, especially trawling, compromises not only the Adriatic ecosystem’s biodiversity (which hosts almost fifty percent of all the Mediterranean marine species), but also the interests of fishers. Between 2004 and 2015, the vessels fishing for deep-water rose shrimp and hake along the eastern coast of Italy fell by 48 and 45 per cent respectively (even if deep-water rose shrimp numbers are currently recovering). Catches of hake and deep-water rose shrimp, in 2014, brought in 15 and 13.5 million euro respectively for Italian trawlers in the Adriatic. However, in the 2004-2015 period there was a drop of 27 per cent in income and 30 per cent in vessel capacity (number, tonnage and engine power).

According to scientists, the regeneration of fish stocks would return fish stocks to healthy levels over the long term, compensating the short term sacrifices entailed by the bans.

The Otranto reserve is part of the network of essential habitats which Medreact and a consortium of research centres, with their AdriaticRecovery initiative launched in 2016, aim to protect for the repopulation of the southern Adriatic. The strategy is guided by both environmental and economic concerns. According to the regional management plan approved by the Italian government in 2018, 18 per cent of the entire Italian peninsula’s fleet and 13 per cent of its trawling production are concentrated in this area. “The coral sea beds in the Strait of Otranto offer a feeding and reproduction site for all commercial species,” explains Carlo Cerrano of Marche Polytechnic University. "The strong underwater currents scatter the fish larvae which grow into adults available for fishers in the areas where fishing is permitted”.

Proof of repopulation’s benefits is the success story in the so-called Pomo Depression, facing Pescara in the central Adriatic. Closed in 2016 by Italy and Croatia, it became an officially protected area by decision of the GFCM in 2017. Recent results show that in only three years the biomass (average weight of specimens) of hake tripled from 60 to 180 kg/km2. This is obviously the right way forward – but complex, as the government acknowledges, caught as it is between EU compliance and safeguarding an employment sector which is already in crisis.

What’s behind the Italian veto

The Italian government may agree with the scientific consensus, but only in principle. While it must protect these reproduction areas, according to EU regulations, it also has to protect an employment sector in serious trouble. Officially, it has blamed its objection on the lack of involvement from the operators and administration of MedReact, the environmental association which presented its initial proposal on the protected area to the GFCM’s Subregional Committee for the Adriatic Sea in 2018. The outcome of this proposal was reliant on the approval of a socio-economic impact report.

“We have repeatedly discussed our proposals with the Fisheries Department of the Agriculture Ministry, which is taking a long time with performing the evaluations requested by GFCM,” explains Domitilla Senni from MedReact. However, Riccardo Rigillo, Director of the Fisheries Department, claims that “the proposal first needs to be looked over by the Mediterranean Advisory Council (MEDAC), where all the concerned parties are represented”. It should be mentioned that MEDAC is an exclusive body of the EU. According to its delegated regulation , the European institutions in Brussels and the EU member states are individually entitled to request opinions relating to fisheries policies, whether European or international. Neither MEDAC nor the individual governments can, however, use such opinions to influence the decisions of GFCM bodies. The GFCM is legally distinct from the EU, composed of its member states as well as non-EU countries, although the European Commission itself is also a contracting party. The European Commission’s Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs clarified the responsibilities of MEDAC last June, in a letter addressed to Giampaolo Buonfiglio, chairman of MEDAC as well as the Alliance of Italian Alliance of Fishing Cooperatives. Buonfiglio continues to support Rigillo, claiming that “a structured consultation with the trade associations is required”.

This bureaucratic impasse has not prevented MedReact from finding a satisfactory agreement, during meetings held in spring, with the Apulian community who regularly fish off the Otranto Strait. As Monopolese ship-owner Giuseppe Danese says, “the trawling ban is only for waters deeper than 600 metres, which neutralises the negative impact since it still allows us to reach species like the deep-water rose shrimp, which in summer represents 80 percent of the fishing”. Last May, MedReact submitted their modified proposal which, upon the insistence of Italy, was postponed for reassessment by the GFCM’s Adriatic working group in 2020. Further studies have been called for, which have yet to be initiated by the Italian government. The postponement found support from Albania, current holders of the rotating presidency of the GFCM, and whose fishing fleet is intensifying its activity in the Strait of Otranto.

By its own admission, the European Commission is now forced by Italy and the Adriatic Committee’s postponement to withdraw the Otranto reserve from negotiations in Athens.

This article is published in collaboration with the European Data Journalism Network and it is released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Tag: EDJNet

Strait of Otranto: Italy vetoes the proposed protected reserve

FAO is negotiating a series of new measures to reduce the devastating impact of trawling and make fishing in the Adriatic Sea sustainable. The institution of the Mediterranean’s largest protected reserve was part of the package, but the Italian government has blocked it

Strait-of-Otranto-Italy-vetoes-the-proposed-protected-reserve

(This article was originally published by MobileReporter/VoxEurop on November 4, 2019)

At their annual meeting held on 4-8 November in Athens, the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM), a special body of the FAO uniting 24 countries north and south of the Mediterranean, is supposed to approve a new action plan for the Adriatic Sea. The document is still confidential, but our investigators have managed to take a peek. The aim of the plan is to combat the alarming fall in demersal fish stocks in the Adriatic. This sea, according to a 2018 study , is the most exploited in the world when it comes to deep sea trawling. According to FAO data , as a proportion of the whole Mediterranean basin, it is also one of the most productive fishing areas: from its waters a little under 200,000 tonnes of fish are landed annually, half of which by Italy.

The package on the negotiation table in Athens includes the following principal measures: reduction of fishing days, a two month ban each year near the coast, a ban on trawling within six nautical miles, a reduction of the minimum fishable size and therefore of net mesh size, and compulsory geolocation systems on all fishing vessels larger than twelve metres to facilitate coast guard checks.

The initial draft of the EU plan included the creation of the largest protected reserve in the Mediterranean: an area of 2,800 square kilometres (twice the area of Rome) located in the international waters of the Strait of Otranto, between Italy and Albania, twelve nautical miles (22 kilometres) from the Apulian coast.

The area is rich in the most threatened and profitable species: deep-water rose shrimp and hake. According to a 2011 study , more than forty percent of the hake which lands on Italian dining tables comes from the Adriatic. Catches of hake in the entire Adriatic are twice its sustainability level, according to a 2017 study by the EU’s Scientific Committee for Fisheries.

Nevertheless, the Italian government has blocked the establishment of this marine sanctuary, judging it rushed, despite the restriction on trawling nets in its waters, agreed with the cooperatives and ship-owners of Monopoli and Mola di Bari. These are the two principal fleets operating in the area, with about forty vessels, docked in the harbours of Brindisi and Otranto respectively, and flanked by other vessels in Salento. The Italian veto also affects the smaller reserve in Bari Canyon.

The need for repopulation of fish stocks

The data shows that overfishing, especially trawling, compromises not only the Adriatic ecosystem’s biodiversity (which hosts almost fifty percent of all the Mediterranean marine species), but also the interests of fishers. Between 2004 and 2015, the vessels fishing for deep-water rose shrimp and hake along the eastern coast of Italy fell by 48 and 45 per cent respectively (even if deep-water rose shrimp numbers are currently recovering). Catches of hake and deep-water rose shrimp, in 2014, brought in 15 and 13.5 million euro respectively for Italian trawlers in the Adriatic. However, in the 2004-2015 period there was a drop of 27 per cent in income and 30 per cent in vessel capacity (number, tonnage and engine power).

According to scientists, the regeneration of fish stocks would return fish stocks to healthy levels over the long term, compensating the short term sacrifices entailed by the bans.

The Otranto reserve is part of the network of essential habitats which Medreact and a consortium of research centres, with their AdriaticRecovery initiative launched in 2016, aim to protect for the repopulation of the southern Adriatic. The strategy is guided by both environmental and economic concerns. According to the regional management plan approved by the Italian government in 2018, 18 per cent of the entire Italian peninsula’s fleet and 13 per cent of its trawling production are concentrated in this area. “The coral sea beds in the Strait of Otranto offer a feeding and reproduction site for all commercial species,” explains Carlo Cerrano of Marche Polytechnic University. "The strong underwater currents scatter the fish larvae which grow into adults available for fishers in the areas where fishing is permitted”.

Proof of repopulation’s benefits is the success story in the so-called Pomo Depression, facing Pescara in the central Adriatic. Closed in 2016 by Italy and Croatia, it became an officially protected area by decision of the GFCM in 2017. Recent results show that in only three years the biomass (average weight of specimens) of hake tripled from 60 to 180 kg/km2. This is obviously the right way forward – but complex, as the government acknowledges, caught as it is between EU compliance and safeguarding an employment sector which is already in crisis.

What’s behind the Italian veto

The Italian government may agree with the scientific consensus, but only in principle. While it must protect these reproduction areas, according to EU regulations, it also has to protect an employment sector in serious trouble. Officially, it has blamed its objection on the lack of involvement from the operators and administration of MedReact, the environmental association which presented its initial proposal on the protected area to the GFCM’s Subregional Committee for the Adriatic Sea in 2018. The outcome of this proposal was reliant on the approval of a socio-economic impact report.

“We have repeatedly discussed our proposals with the Fisheries Department of the Agriculture Ministry, which is taking a long time with performing the evaluations requested by GFCM,” explains Domitilla Senni from MedReact. However, Riccardo Rigillo, Director of the Fisheries Department, claims that “the proposal first needs to be looked over by the Mediterranean Advisory Council (MEDAC), where all the concerned parties are represented”. It should be mentioned that MEDAC is an exclusive body of the EU. According to its delegated regulation , the European institutions in Brussels and the EU member states are individually entitled to request opinions relating to fisheries policies, whether European or international. Neither MEDAC nor the individual governments can, however, use such opinions to influence the decisions of GFCM bodies. The GFCM is legally distinct from the EU, composed of its member states as well as non-EU countries, although the European Commission itself is also a contracting party. The European Commission’s Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs clarified the responsibilities of MEDAC last June, in a letter addressed to Giampaolo Buonfiglio, chairman of MEDAC as well as the Alliance of Italian Alliance of Fishing Cooperatives. Buonfiglio continues to support Rigillo, claiming that “a structured consultation with the trade associations is required”.

This bureaucratic impasse has not prevented MedReact from finding a satisfactory agreement, during meetings held in spring, with the Apulian community who regularly fish off the Otranto Strait. As Monopolese ship-owner Giuseppe Danese says, “the trawling ban is only for waters deeper than 600 metres, which neutralises the negative impact since it still allows us to reach species like the deep-water rose shrimp, which in summer represents 80 percent of the fishing”. Last May, MedReact submitted their modified proposal which, upon the insistence of Italy, was postponed for reassessment by the GFCM’s Adriatic working group in 2020. Further studies have been called for, which have yet to be initiated by the Italian government. The postponement found support from Albania, current holders of the rotating presidency of the GFCM, and whose fishing fleet is intensifying its activity in the Strait of Otranto.

By its own admission, the European Commission is now forced by Italy and the Adriatic Committee’s postponement to withdraw the Otranto reserve from negotiations in Athens.

This article is published in collaboration with the European Data Journalism Network and it is released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Tag: EDJNet