In memory of the dead in Europe

Activists and groups trying to restore human dignity and, when possible, name to individuals who lost their lives along the Balkan routes, recently organised a commemoration at the cemetery in Loznica. Report

Lapidi e croci dei NN, cimitero di Loznica – Foto Silvia Maraone

Tombstones and the NN crosses at the cemetery in Loznica © photo by Silvia Maraone

We leave early on Sunday [25 January, ed.]. With my female colleagues, who are completing a year of Universal Civil Service as part of the IPSIA program in Bihać, I set off from the western border to the opposite end of the Bosnian route. My companions sleep while our white van makes its way through the downpour that follows us to Serbia. After a few hours of driving, we arrive at the Šepak border crossing, beyond which lies the city of Loznica. The welcome at these borders is never accompanied by smiles, and this time, next to the grumpy Serbian border guards, we notice new blue all-terrain vehicles parked next to border police cars: in block letters on the side, we read Frontex (European Border and Coast Guard Agency). They will be our companions, visible or invisible, during this entire journey along the Drina, and then along the Una.

We set off to meet Nihad Suljić. Nihad is not a politician and does not work for large international organisations. He is a kind, sincere and devoted young man from Tuzla, whose life changed in 2018 during the mass arrival of migrants in his city. I met Nihad in those years at the bus station, where dozens of people departed every day. Together with his friends, he was constantly engaged in collecting and distributing clothes, food and diapers, but above all he tried to restore dignity to people on the move, connecting with them in the most sincere way, spontaneously, with a smile and open arms, giving a hug to the people he and his friends call brothers and sisters.

Organised by SOS Balkan Route, Leave No One Behind and Deluj.ba, which help people traveling the Balkan route, a commemoration was held on 27 January at the cemetery in Loznica, a Serbian town separated from Zvornik in Bosnia and Herzegovina by the Drina river. This area is a mandatory route for migrants trying to reach Bosnia and Herzegovina. Nineteen unidentified migrants, whose identity has never been established, were buried at the Loznica cemetery, while nine identified migrants were buried at the Muslim cemetery in Loznica. The old wooden gravestones, which were in poor condition, were replaced with more permanent ones. Silvia Maraone, project manager at IPSIA – which works in Bihać on support projects for migrants and asylum seekers and has long cooperated with other organisations active in the area – participated in the trip and commemoration.

Over the years, we talked and met on several occasions. Nihad is to Drina what I am to Una: we are the guardians of the two deadliest borders along this Balkan route. These borders, which kill, are made of merciless rivers and mountains, and are monitored by border police who do not let anyone pass, unquestioningly obeying the orders that come from an increasingly closed and violent Europe. We do not want members of the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) at the Olympic Games in Milan, but we do not react when European police officers, just a few kilometers from the Italian border, break the teeth and bones of men, women and children and, pushing them back, let them die.

The SOS Balkan Route association, headed by a wonderful human being, rapper Kid Pex – that is, Petar Rosandić, better known as Pero – has been taking care of the living and the dead for several years. In addition to providing motivational and humanitarian support along the route, Pero helps his Balkan friends, such as Baba Asim and Nihad, restore dignity to the nameless dead buried in cemeteries along the border.

NN – Nomen Nescio. If you want to dehumanise a human being, it is easy: start by taking away their name. The graves along the Balkan route are multiplying: a multitude of NN, unidentified persons who were someone.

The first tombstone for me is that of Madina Hussiny, a girl who lost her life trying to cross the border between Serbia and Croatia with her family. I remember Madina running and playing in the Bogovađa camp. She left for the game and then they buried her tiny body in the cemetery in Šid, marking the place with a small, unstable wooden tombstone. For Madina, together with a dear friend and the local Caritas team, I made perhaps one of the first permanent tombstones along the Balkan route. The old wooden tombstones have already rotted away, and almost all trace of those buried near Madina has been lost.

This is precisely the reason for which Nihad is fighting, for which Baba Asim is fighting, for which we are all fighting at the borders. The memory must last and tell the story. If the living do not do it, the dead will, for us and for others. That is why simple marble tombstones, black or white, with names whenever possible, are being erected in Bihać, Zvornik, Karakaj and Bijeljina, in order to preserve the memory of the people who existed and passed by us, and who will forever remain on that border, whether the citizens of these countries and all of us like it or not.

I write to Pero. He is glad that we came to see Nihad, who seems to me more tired than usual, nervous, maybe even a little scared. Here he is alone, his friends only arrive on the day of the commemoration. In the evening we wander around Loznica, Chetnik slogans and the mottos of Parizan and Crvena Zvezda, clubs that have always attracted hooligans and violent fans, are written on the walls of buildings. Loznica is a town left to itself, in ruins. I realise this the next day, when we set out to scout the border, starting from the largest squat in this area, more precisely from the industrial complex of the former viscose factory.

Former viscose factory and barracks where migrants sleep © photo by Silvia Maraone

Viscose chemical industry (HI Viskoza) was a textile giant whose functioning was guaranteed by Italian machines. Over 11,000 people worked in eleven factory buildings, opened in 1957. A true city within a city, of which only ruins remain today. With the introduction of sanctions against Serbia in the 1990s, Viskoza was cut off from foreign markets. Without exporting and without the possibility of importing raw materials and spare parts, production decreased sharply, until the factory was closed in 2005. Bankruptcy was officially declared in 2009, after a fire destroyed the factory in 2008, releasing toxic waste and chemical gases. After the closure of the factory that employed the entire population, the city came to a standstill. The facades of the old workers’ buildings are crumbling, the pubs are full of drunken pensioners who have lost everything, and young people study to be able to leave.

On Monday, 26 January, in the morning, after visiting the Orthodox cemetery and then the Muslim one to make sure that everything is ready for the next day, we enter the driveway leading to the factory buildings to determine whether migrants are still hiding here or what appears to be a decrease in the number of border crossings near Loznica actually corresponds to reality.

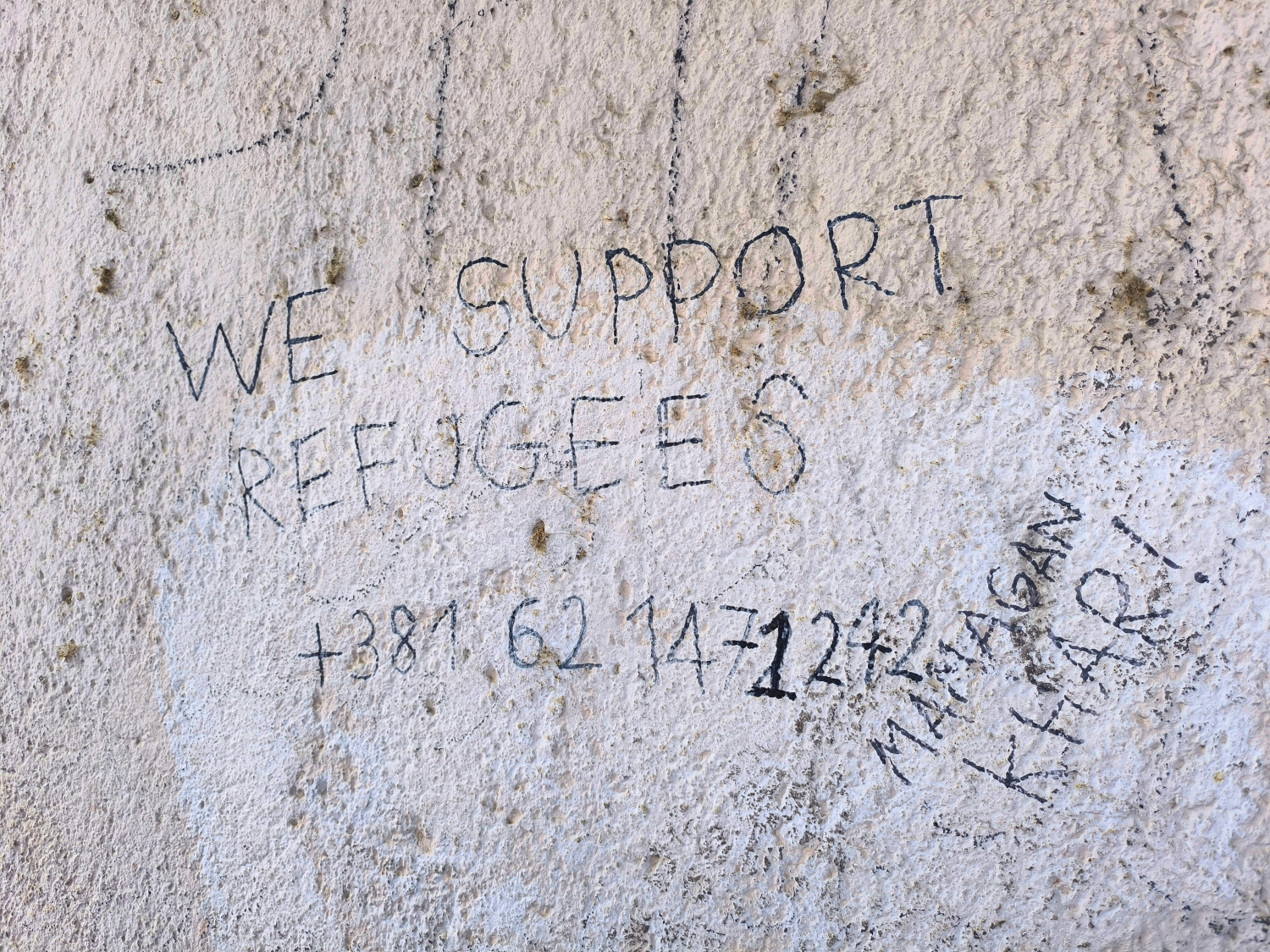

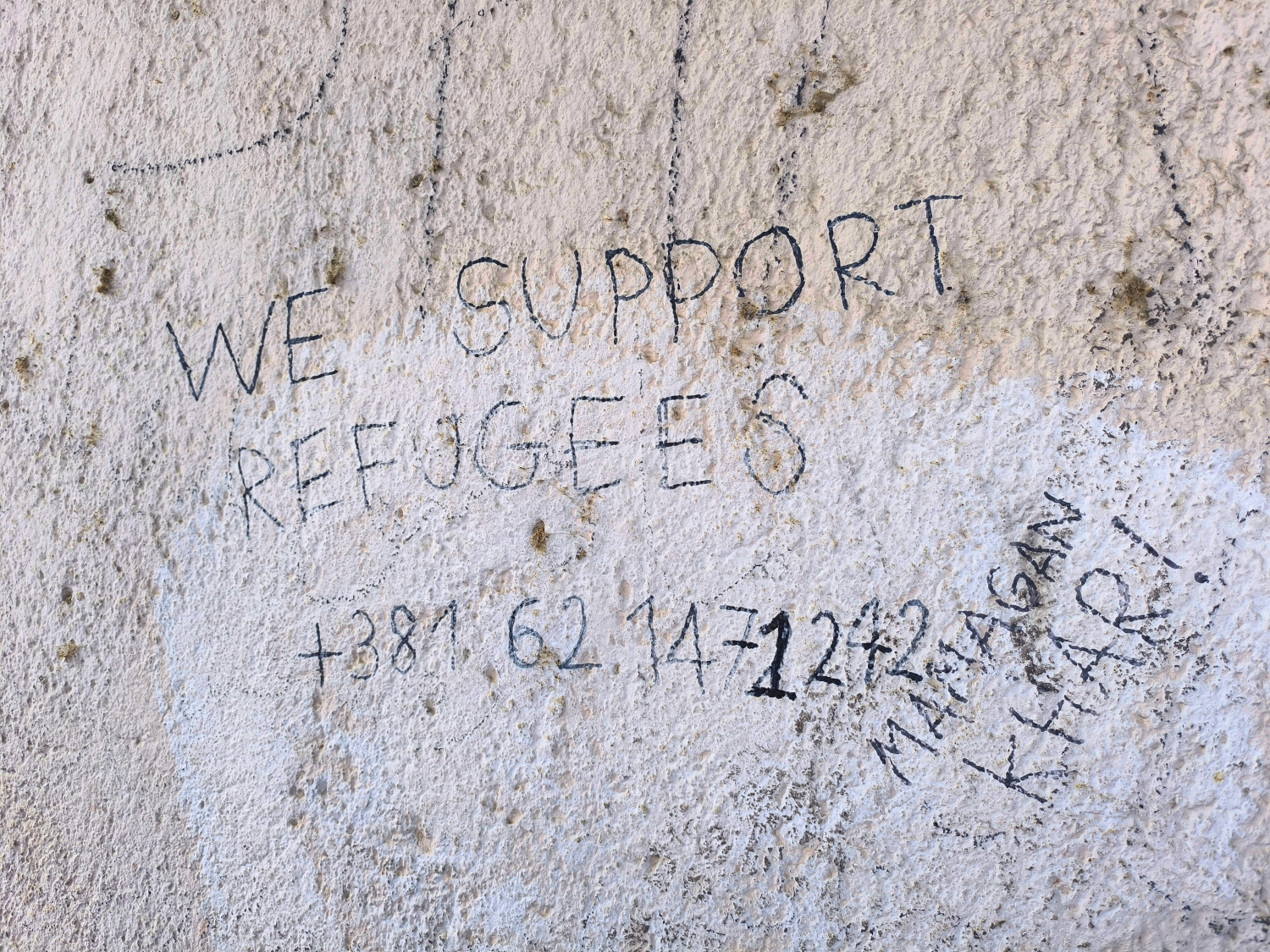

The buildings are unstable and partly covered with vegetation that is slowly swallowing the concrete, but it does not take a trained eye to spot traces of human presence. The increasing number of empty cans of energy drinks, inseparable companions of those who have to walk for hours at night, emptied food packages and the occasional forgotten item of clothing, indicate which barracks serve as temporary shelters for those preparing to cross the border. However, it is clear that these large warehouses have become a ghostly place. The graffiti on the walls is old, faded by time and humidity. Alongside the dates and signatures of those who have passed through here, we can still read the phone numbers of international organisations offering assistance.

Messages of solidarity on the walls © photo Silvia Maraone

The impression that follows us along the eastern border these days is that the repressive measures implemented by the Serbian government in recent years have pushed people on the move even further into the shadows, making their journey even more invisible and, consequently, more dangerous.

We return to the van, the white color of which is practically invisible under the layer of mud, which sticks to our soles, and we head towards Banja Koviljača. This town, like Loznica, tells us about a past that once exuded prosperity thanks to the local spa, which was visited by King Karađorđević during the monarchy, and which today resembles abandoned movie sets. We stop at the old railway station. This building was once the center of humanity on the move. Namely, in Banja Koviljača there was one of the first centers for asylum and reception in Serbia, but with the increase in the number of arrivals, the camp became too small and the station was turned into a permanent squat.

Remains of the station in Banja Koviljača © photo by Silvia Maraone

An armed clash between groups of human traffickers near the station gave the Serbian government and local authorities the pretext to intervene in 2023. First, all informal shelters were emptied, then the camp was closed, and the migrants were driven away from the border, as is done in the north of the country.

Today, the station is completely abandoned, just like the Viskoza factory. However, the traces of those who passed through are visible everywhere: above the migrants’ graffiti, the names and dates of those who dreamed of Europe are crossed out in large orange Cyrillic letters. Swastikas and blasphemies against Allah cover the messages and names of those who have passed through, a tangible sign of hostility that has replaced what was once hospitality, or at least tolerance.

The man watches us and asks Nihad why we are here. Smiling, Nihad replies that we are researching the Serbian railway. I immediately come to his aid and start talking about the Una Railway that runs from Bihać to the sea. I say that it is a shame that the railways have collapsed throughout the former Yugoslavia. I call my colleagues to come back, and then in the van, Nihad and I, laughing, tell them what we have quickly come up with by improvising. The previous evening, at the bus station, we played the same game: Nihad started a conversation with the station master to find out when the bus from Belgrade would arrive, because we expected migrants to be on it. But to sound credible, we said that we were waiting for our friend Slavica, whose phone was switched off and we did not know if she was on the bus.

We leave the station so as not to become too suspicious and head towards Mali Zvornik. The van barely climbs to the small town cemetery on the hill. We park and, on our left, we see Muslim graves. From there we set off in search of traces of five graves. Nihad knows that five people are buried at this place, but he has never been able to find their graves. After failing to find special signs of anonymous grave sites, we move on to the Orthodox part of the cemetery, but there too we find no traces of people who lost their lives crossing the Drina.

Border along the Drina River near Zvornik, Bosnia and Herzegovina © photo Silvia Maraone

At one point, a man from a local funeral home approaches us and, extremely generously, offers to show us the exact spot where they are buried. They are buried in two empty places that are not marked at all by a wooden tombstone, coffin or cross as a reminder that human beings rest here. Nihad leaves the man his contact information, explaining his project, in the hope that he will succeed here too in bringing the seeds of friendship and restoring dignity to missing persons, by building real tombstones. The man proves to be extremely open and tolerant, says that he wants to help Nihad and tells us how he has met migrants several times and tried to help them. This is perhaps the first time since this morning that I have seen Nihad calmer.

We continue our journey towards today’s final destination, the Ljubovija border crossing. On the other side is Bratunac, and a few kilometers further the Memorial Center Potočari and Srebrenica. As we go along the Drina, Nihad’s narration is permeated with stories about the massacre committed in this area and the genocide of 1995. He tells us about mass graves discovered along the border, tortures, rapes, murders. Here he helps elderly women who returned to their homes after the war and live alone, without husbands and children, killed in that terrible July 1995. He visits them, brings them food, spends time with them, even though no one asks him to do this and no one knows about it.

Driving back towards Loznica, while the sun is setting, Nihad quotes a frase that someone once told him, which has remained etched in his memory: we should not be surprised that people in these places do not show compassion towards refugees and migrants, because these people, thirty years ago, created refugees. I continue driving, and then, a few kilometers from the railway bridge under which the migrants pass, we see Frontex and border police patrols stopping the cars. We are offended that they did not stop our van, obviously suspicious, completely dirty and with Bosnian license plates, we turn around to pass the patrol again. Nothing. I say to Nihad: “The third time is the charm”. He laughs, but again nothing. Frontex seems to be stopping vehicles at random.

We arrive in Loznica and, before going to dinner, we pass by the bridge that marks the border between Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Under the bridge we find traces of shoes and food. Nihad plays us a video that a Moroccan showed him: people pull themselves up with a rope under the pillars and then cross under the metal structure that supports the bridge, risking their lives. This is where most of the people lost thier lives. A Serbian border policeman looks at us, leans over the bridge and shouts: “No photos, go away!”. Fearing him more than Frontex, we move and, upon returning to the guesthouse, agree to meet Nihad the next morning, first for coffee and then at the cemetery, where the rest of the delegation and journalists will join us.

We wake up and together with Nihad and Dževida, a volunteer who joined us from Tuzla, we go to the cemetery. On International Holocaust Remembrance Day, 27 January, we pause to remember the horrors of the Holocaust and solemnly promise “never again”. Today, in this place, that “never again” rings hollow. The ghosts of people killed in 1995 and buried in mass graves a few kilometers from here are looking at us, along with the spirits of the new dead. Almost all of them died young, and their only fault was that they were born in countries like Syria or Afghanistan. They are also buried namesless in miserable mass graves, alongside those of other innocents.

Interreligious commemoration in Loznica © photo by Silvia Maraone

At least the sun is shining today. In front of the city cemetery, we are joined by Pero and other members of SOS Balkanroute, activists of the organisation Leave No One Behind and Baba Asim, who arrived from Bihać. We are here because we want to say that this border cannot be a wall of silence. Next to us are the imam of Loznica and his associates, the president of the Belgrade Majlis Tafa ef Beriša and the Archbishop of Belgrade László Német. Representatives of the Orthodox community, which is the majority in Serbia, are not present due to prior commitments, so we were told.

The first part of the ceremony took place in front of the new black tombstones in the Orthodox cemetery, where nineteen unidentified people rest. It is here that Archbishop Német reminds: “Every human being has infinite value. […] Migrations occur due to wars, violence and climate change, whether we call them legal or illegal, but this does not change the dignity of these people. God is much more merciful than all our laws, regulations and border services”.

Standing next to the archbishop, Pero emphasises the political nature of this day. “What we are doing today is not an act of mercy, but of civic resistance against oblivion. While Europe is investing billions in drones and fences, here we are spending what little money we have to buy stones and carve names on them”.

The NN graves at the Muslim cemetery in Loznica © photo by Silvia Maraone

Then we move on to a small Muslim cemetery, a few hundred meters away. Nihad stands behind a memorial plaque engraved with the names of several people who were buried in the cemetery, but the exact location of their graves is unknown. Among them is a man who lost his life in the Bogovađa asylum center, where I worked for two years and where I met little Madina Hussiny. Another girl, Madina Bibi, lost her life there. Her body was not buried in Bogovađa: despite the fact that she was just over three years old and innocent, the locals did not want her to be buried there, so she was buried in Lazarevac. The same fate befell this man, who did not find peace near the place where he died, because of the religion and destructive ideology that still flows through the veins of the inhabitants of this country. The harsh comments that we will read on social media in Loznica and beyond, under the articles published after the ceremony, confirm the hatred that pulses through the veins of these people, who live amidst the ruins of their factories and their past, in a miserable present.

Nihad Suljić speaks in memory of those who lost their lives at the border © photo Silvia Maraone

It is near these graves – white ones this time – that Nihad calmly recounts a terrible accident that occurred in 2024, when a seventeen-year-old boy from Serbia let too many people into a small boat, which then capsised. Among the victims were Fatima, Ahmad and their daughter Lana, who was only nine months old.

Nihad reads us a letter from Muhamed Hilal, Lana’s uncle, who confided his words to him. “I am here with you today, through the words spoken on my behalf. Although almost a year and a half has passed since the tragedy, the pain is as present as if it happened yesterday. My brother, his wife and their daughter were not looking for adventure, but for safety and a life of dignity. Refugees are not numbers or statistics, but people with names, families and dreams”.

As the letter ends with the prayer “To Allah we belong and to Him we will return”, Nihad takes the floor for a final, poignant farewell, asking forgiveness from the little girl who now finally has a grave. “We are here to ask forgiveness from Lana and her family. They did not die in an accident, they died because there was no safe passage. People do not die because the Drina is dangerous, they die because European policies push them into the river”.

Nihad and Pero utter further words of condemnation. “Our goal was not just to arrange the graves, but to preserve the memory and restore dignity to people who did not have it, even on their last journey. If they did not have a dignified life, let them have it in death”. Nihad then adds another fact: the average age of the victims is just 23. He concludes: “Their only sin was having a passport that was not good enough”.

The imam recites a prayer for the dead. As he sings, black crows caw and join in the prayer, soaring as if in a pre-rehearsed choreography.

At the end of the ceremony, after the journalists left and after saying goodbye to his friends, Nihad, for the first time, seemes to breathe. We return to the van and set off again. We accompany Nihad to Tuzla, where he proudly shows us the headquarters of his new association Djeluj.ba.

He is tired, grateful and ready for his next battles: first of all, returning to Sarajevo to be with the young men from Sudan who, after trying to cross the mountain border near Bihać, had their legs and arms amputated due to the frozen river Plješevica. Nihad takes care of them, helps them eat and wash, prays with them and collects funds to buy the prostheses they need, as he tells me, to get out of Bosnia as soon as possible.

After hours of traveling in darkness and silence, a few kilometers from Bihać, the road after Bosanska Krupa is blocked. Flashing blue lights in the dark, I think of an accident, but these are controls, carried out by mixed patrols. Frontex does not stop us this time either, they let us pass through the darkness, not knowing that in this muddy van there are not only people traveling, but also the names and stories of those they tried to make invisible, and that, thanks to a young man from Tuzla, remain forever carved in marble.

Featured articles

In memory of the dead in Europe

Activists and groups trying to restore human dignity and, when possible, name to individuals who lost their lives along the Balkan routes, recently organised a commemoration at the cemetery in Loznica. Report

Lapidi e croci dei NN, cimitero di Loznica – Foto Silvia Maraone

Tombstones and the NN crosses at the cemetery in Loznica © photo by Silvia Maraone

We leave early on Sunday [25 January, ed.]. With my female colleagues, who are completing a year of Universal Civil Service as part of the IPSIA program in Bihać, I set off from the western border to the opposite end of the Bosnian route. My companions sleep while our white van makes its way through the downpour that follows us to Serbia. After a few hours of driving, we arrive at the Šepak border crossing, beyond which lies the city of Loznica. The welcome at these borders is never accompanied by smiles, and this time, next to the grumpy Serbian border guards, we notice new blue all-terrain vehicles parked next to border police cars: in block letters on the side, we read Frontex (European Border and Coast Guard Agency). They will be our companions, visible or invisible, during this entire journey along the Drina, and then along the Una.

We set off to meet Nihad Suljić. Nihad is not a politician and does not work for large international organisations. He is a kind, sincere and devoted young man from Tuzla, whose life changed in 2018 during the mass arrival of migrants in his city. I met Nihad in those years at the bus station, where dozens of people departed every day. Together with his friends, he was constantly engaged in collecting and distributing clothes, food and diapers, but above all he tried to restore dignity to people on the move, connecting with them in the most sincere way, spontaneously, with a smile and open arms, giving a hug to the people he and his friends call brothers and sisters.

Organised by SOS Balkan Route, Leave No One Behind and Deluj.ba, which help people traveling the Balkan route, a commemoration was held on 27 January at the cemetery in Loznica, a Serbian town separated from Zvornik in Bosnia and Herzegovina by the Drina river. This area is a mandatory route for migrants trying to reach Bosnia and Herzegovina. Nineteen unidentified migrants, whose identity has never been established, were buried at the Loznica cemetery, while nine identified migrants were buried at the Muslim cemetery in Loznica. The old wooden gravestones, which were in poor condition, were replaced with more permanent ones. Silvia Maraone, project manager at IPSIA – which works in Bihać on support projects for migrants and asylum seekers and has long cooperated with other organisations active in the area – participated in the trip and commemoration.

Over the years, we talked and met on several occasions. Nihad is to Drina what I am to Una: we are the guardians of the two deadliest borders along this Balkan route. These borders, which kill, are made of merciless rivers and mountains, and are monitored by border police who do not let anyone pass, unquestioningly obeying the orders that come from an increasingly closed and violent Europe. We do not want members of the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) at the Olympic Games in Milan, but we do not react when European police officers, just a few kilometers from the Italian border, break the teeth and bones of men, women and children and, pushing them back, let them die.

The SOS Balkan Route association, headed by a wonderful human being, rapper Kid Pex – that is, Petar Rosandić, better known as Pero – has been taking care of the living and the dead for several years. In addition to providing motivational and humanitarian support along the route, Pero helps his Balkan friends, such as Baba Asim and Nihad, restore dignity to the nameless dead buried in cemeteries along the border.

NN – Nomen Nescio. If you want to dehumanise a human being, it is easy: start by taking away their name. The graves along the Balkan route are multiplying: a multitude of NN, unidentified persons who were someone.

The first tombstone for me is that of Madina Hussiny, a girl who lost her life trying to cross the border between Serbia and Croatia with her family. I remember Madina running and playing in the Bogovađa camp. She left for the game and then they buried her tiny body in the cemetery in Šid, marking the place with a small, unstable wooden tombstone. For Madina, together with a dear friend and the local Caritas team, I made perhaps one of the first permanent tombstones along the Balkan route. The old wooden tombstones have already rotted away, and almost all trace of those buried near Madina has been lost.

This is precisely the reason for which Nihad is fighting, for which Baba Asim is fighting, for which we are all fighting at the borders. The memory must last and tell the story. If the living do not do it, the dead will, for us and for others. That is why simple marble tombstones, black or white, with names whenever possible, are being erected in Bihać, Zvornik, Karakaj and Bijeljina, in order to preserve the memory of the people who existed and passed by us, and who will forever remain on that border, whether the citizens of these countries and all of us like it or not.

I write to Pero. He is glad that we came to see Nihad, who seems to me more tired than usual, nervous, maybe even a little scared. Here he is alone, his friends only arrive on the day of the commemoration. In the evening we wander around Loznica, Chetnik slogans and the mottos of Parizan and Crvena Zvezda, clubs that have always attracted hooligans and violent fans, are written on the walls of buildings. Loznica is a town left to itself, in ruins. I realise this the next day, when we set out to scout the border, starting from the largest squat in this area, more precisely from the industrial complex of the former viscose factory.

Former viscose factory and barracks where migrants sleep © photo by Silvia Maraone

Viscose chemical industry (HI Viskoza) was a textile giant whose functioning was guaranteed by Italian machines. Over 11,000 people worked in eleven factory buildings, opened in 1957. A true city within a city, of which only ruins remain today. With the introduction of sanctions against Serbia in the 1990s, Viskoza was cut off from foreign markets. Without exporting and without the possibility of importing raw materials and spare parts, production decreased sharply, until the factory was closed in 2005. Bankruptcy was officially declared in 2009, after a fire destroyed the factory in 2008, releasing toxic waste and chemical gases. After the closure of the factory that employed the entire population, the city came to a standstill. The facades of the old workers’ buildings are crumbling, the pubs are full of drunken pensioners who have lost everything, and young people study to be able to leave.

On Monday, 26 January, in the morning, after visiting the Orthodox cemetery and then the Muslim one to make sure that everything is ready for the next day, we enter the driveway leading to the factory buildings to determine whether migrants are still hiding here or what appears to be a decrease in the number of border crossings near Loznica actually corresponds to reality.

The buildings are unstable and partly covered with vegetation that is slowly swallowing the concrete, but it does not take a trained eye to spot traces of human presence. The increasing number of empty cans of energy drinks, inseparable companions of those who have to walk for hours at night, emptied food packages and the occasional forgotten item of clothing, indicate which barracks serve as temporary shelters for those preparing to cross the border. However, it is clear that these large warehouses have become a ghostly place. The graffiti on the walls is old, faded by time and humidity. Alongside the dates and signatures of those who have passed through here, we can still read the phone numbers of international organisations offering assistance.

Messages of solidarity on the walls © photo Silvia Maraone

The impression that follows us along the eastern border these days is that the repressive measures implemented by the Serbian government in recent years have pushed people on the move even further into the shadows, making their journey even more invisible and, consequently, more dangerous.

We return to the van, the white color of which is practically invisible under the layer of mud, which sticks to our soles, and we head towards Banja Koviljača. This town, like Loznica, tells us about a past that once exuded prosperity thanks to the local spa, which was visited by King Karađorđević during the monarchy, and which today resembles abandoned movie sets. We stop at the old railway station. This building was once the center of humanity on the move. Namely, in Banja Koviljača there was one of the first centers for asylum and reception in Serbia, but with the increase in the number of arrivals, the camp became too small and the station was turned into a permanent squat.

Remains of the station in Banja Koviljača © photo by Silvia Maraone

An armed clash between groups of human traffickers near the station gave the Serbian government and local authorities the pretext to intervene in 2023. First, all informal shelters were emptied, then the camp was closed, and the migrants were driven away from the border, as is done in the north of the country.

Today, the station is completely abandoned, just like the Viskoza factory. However, the traces of those who passed through are visible everywhere: above the migrants’ graffiti, the names and dates of those who dreamed of Europe are crossed out in large orange Cyrillic letters. Swastikas and blasphemies against Allah cover the messages and names of those who have passed through, a tangible sign of hostility that has replaced what was once hospitality, or at least tolerance.

The man watches us and asks Nihad why we are here. Smiling, Nihad replies that we are researching the Serbian railway. I immediately come to his aid and start talking about the Una Railway that runs from Bihać to the sea. I say that it is a shame that the railways have collapsed throughout the former Yugoslavia. I call my colleagues to come back, and then in the van, Nihad and I, laughing, tell them what we have quickly come up with by improvising. The previous evening, at the bus station, we played the same game: Nihad started a conversation with the station master to find out when the bus from Belgrade would arrive, because we expected migrants to be on it. But to sound credible, we said that we were waiting for our friend Slavica, whose phone was switched off and we did not know if she was on the bus.

We leave the station so as not to become too suspicious and head towards Mali Zvornik. The van barely climbs to the small town cemetery on the hill. We park and, on our left, we see Muslim graves. From there we set off in search of traces of five graves. Nihad knows that five people are buried at this place, but he has never been able to find their graves. After failing to find special signs of anonymous grave sites, we move on to the Orthodox part of the cemetery, but there too we find no traces of people who lost their lives crossing the Drina.

Border along the Drina River near Zvornik, Bosnia and Herzegovina © photo Silvia Maraone

At one point, a man from a local funeral home approaches us and, extremely generously, offers to show us the exact spot where they are buried. They are buried in two empty places that are not marked at all by a wooden tombstone, coffin or cross as a reminder that human beings rest here. Nihad leaves the man his contact information, explaining his project, in the hope that he will succeed here too in bringing the seeds of friendship and restoring dignity to missing persons, by building real tombstones. The man proves to be extremely open and tolerant, says that he wants to help Nihad and tells us how he has met migrants several times and tried to help them. This is perhaps the first time since this morning that I have seen Nihad calmer.

We continue our journey towards today’s final destination, the Ljubovija border crossing. On the other side is Bratunac, and a few kilometers further the Memorial Center Potočari and Srebrenica. As we go along the Drina, Nihad’s narration is permeated with stories about the massacre committed in this area and the genocide of 1995. He tells us about mass graves discovered along the border, tortures, rapes, murders. Here he helps elderly women who returned to their homes after the war and live alone, without husbands and children, killed in that terrible July 1995. He visits them, brings them food, spends time with them, even though no one asks him to do this and no one knows about it.

Driving back towards Loznica, while the sun is setting, Nihad quotes a frase that someone once told him, which has remained etched in his memory: we should not be surprised that people in these places do not show compassion towards refugees and migrants, because these people, thirty years ago, created refugees. I continue driving, and then, a few kilometers from the railway bridge under which the migrants pass, we see Frontex and border police patrols stopping the cars. We are offended that they did not stop our van, obviously suspicious, completely dirty and with Bosnian license plates, we turn around to pass the patrol again. Nothing. I say to Nihad: “The third time is the charm”. He laughs, but again nothing. Frontex seems to be stopping vehicles at random.

We arrive in Loznica and, before going to dinner, we pass by the bridge that marks the border between Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Under the bridge we find traces of shoes and food. Nihad plays us a video that a Moroccan showed him: people pull themselves up with a rope under the pillars and then cross under the metal structure that supports the bridge, risking their lives. This is where most of the people lost thier lives. A Serbian border policeman looks at us, leans over the bridge and shouts: “No photos, go away!”. Fearing him more than Frontex, we move and, upon returning to the guesthouse, agree to meet Nihad the next morning, first for coffee and then at the cemetery, where the rest of the delegation and journalists will join us.

We wake up and together with Nihad and Dževida, a volunteer who joined us from Tuzla, we go to the cemetery. On International Holocaust Remembrance Day, 27 January, we pause to remember the horrors of the Holocaust and solemnly promise “never again”. Today, in this place, that “never again” rings hollow. The ghosts of people killed in 1995 and buried in mass graves a few kilometers from here are looking at us, along with the spirits of the new dead. Almost all of them died young, and their only fault was that they were born in countries like Syria or Afghanistan. They are also buried namesless in miserable mass graves, alongside those of other innocents.

Interreligious commemoration in Loznica © photo by Silvia Maraone

At least the sun is shining today. In front of the city cemetery, we are joined by Pero and other members of SOS Balkanroute, activists of the organisation Leave No One Behind and Baba Asim, who arrived from Bihać. We are here because we want to say that this border cannot be a wall of silence. Next to us are the imam of Loznica and his associates, the president of the Belgrade Majlis Tafa ef Beriša and the Archbishop of Belgrade László Német. Representatives of the Orthodox community, which is the majority in Serbia, are not present due to prior commitments, so we were told.

The first part of the ceremony took place in front of the new black tombstones in the Orthodox cemetery, where nineteen unidentified people rest. It is here that Archbishop Német reminds: “Every human being has infinite value. […] Migrations occur due to wars, violence and climate change, whether we call them legal or illegal, but this does not change the dignity of these people. God is much more merciful than all our laws, regulations and border services”.

Standing next to the archbishop, Pero emphasises the political nature of this day. “What we are doing today is not an act of mercy, but of civic resistance against oblivion. While Europe is investing billions in drones and fences, here we are spending what little money we have to buy stones and carve names on them”.

The NN graves at the Muslim cemetery in Loznica © photo by Silvia Maraone

Then we move on to a small Muslim cemetery, a few hundred meters away. Nihad stands behind a memorial plaque engraved with the names of several people who were buried in the cemetery, but the exact location of their graves is unknown. Among them is a man who lost his life in the Bogovađa asylum center, where I worked for two years and where I met little Madina Hussiny. Another girl, Madina Bibi, lost her life there. Her body was not buried in Bogovađa: despite the fact that she was just over three years old and innocent, the locals did not want her to be buried there, so she was buried in Lazarevac. The same fate befell this man, who did not find peace near the place where he died, because of the religion and destructive ideology that still flows through the veins of the inhabitants of this country. The harsh comments that we will read on social media in Loznica and beyond, under the articles published after the ceremony, confirm the hatred that pulses through the veins of these people, who live amidst the ruins of their factories and their past, in a miserable present.

Nihad Suljić speaks in memory of those who lost their lives at the border © photo Silvia Maraone

It is near these graves – white ones this time – that Nihad calmly recounts a terrible accident that occurred in 2024, when a seventeen-year-old boy from Serbia let too many people into a small boat, which then capsised. Among the victims were Fatima, Ahmad and their daughter Lana, who was only nine months old.

Nihad reads us a letter from Muhamed Hilal, Lana’s uncle, who confided his words to him. “I am here with you today, through the words spoken on my behalf. Although almost a year and a half has passed since the tragedy, the pain is as present as if it happened yesterday. My brother, his wife and their daughter were not looking for adventure, but for safety and a life of dignity. Refugees are not numbers or statistics, but people with names, families and dreams”.

As the letter ends with the prayer “To Allah we belong and to Him we will return”, Nihad takes the floor for a final, poignant farewell, asking forgiveness from the little girl who now finally has a grave. “We are here to ask forgiveness from Lana and her family. They did not die in an accident, they died because there was no safe passage. People do not die because the Drina is dangerous, they die because European policies push them into the river”.

Nihad and Pero utter further words of condemnation. “Our goal was not just to arrange the graves, but to preserve the memory and restore dignity to people who did not have it, even on their last journey. If they did not have a dignified life, let them have it in death”. Nihad then adds another fact: the average age of the victims is just 23. He concludes: “Their only sin was having a passport that was not good enough”.

The imam recites a prayer for the dead. As he sings, black crows caw and join in the prayer, soaring as if in a pre-rehearsed choreography.

At the end of the ceremony, after the journalists left and after saying goodbye to his friends, Nihad, for the first time, seemes to breathe. We return to the van and set off again. We accompany Nihad to Tuzla, where he proudly shows us the headquarters of his new association Djeluj.ba.

He is tired, grateful and ready for his next battles: first of all, returning to Sarajevo to be with the young men from Sudan who, after trying to cross the mountain border near Bihać, had their legs and arms amputated due to the frozen river Plješevica. Nihad takes care of them, helps them eat and wash, prays with them and collects funds to buy the prostheses they need, as he tells me, to get out of Bosnia as soon as possible.

After hours of traveling in darkness and silence, a few kilometers from Bihać, the road after Bosanska Krupa is blocked. Flashing blue lights in the dark, I think of an accident, but these are controls, carried out by mixed patrols. Frontex does not stop us this time either, they let us pass through the darkness, not knowing that in this muddy van there are not only people traveling, but also the names and stories of those they tried to make invisible, and that, thanks to a young man from Tuzla, remain forever carved in marble.