Home sweet home, a human right. But not for everyone

Four hundred thousand homeless minors, apartments at unaffordable prices, families living in the cold. Housing has become a luxury. The EU is taking action to ensure compliance with one of the principles of cohesion policy: affordable housing

© beeboys/Shutterstock

© beeboys/Shutterstock

In 2024, 1.3 million people in Europe were homeless. That is 20 out of every 10,000 inhabitants. Among them, 400,000 children. In the United States, a country often referred to as the nation of the homeless, there were 770,000 homeless people. That is 23 out of every 10,000 inhabitants. These are stark figures, exposing a vulnerability we thought was unique to the United States.

However, housing difficulties are not limited to those without a home. They affect a large segment of the European population: those struggling to make ends meet to pay rent and bills, those forced to live in unhealthy housing, and the 47 million who cannot heat their homes. Added to this are rising prices caused by the frenzy of short-term rentals and the resulting housing shortage. From 2010 to 2024, housing costs have risen by 48%, while wages have stagnated. Renting an apartment in Paris costs an average of 48.8 euros per square meter, just over 30 euros in Rome, Berlin and Milan, compared to 17.1 euros in Athens. The reality is often far from an ideal world where, to avoid housing cost overburden, one should spend no more than 40% of one’s income on housing costs, including rent, mortgage, utilities and maintenance.

Sustainable, functional and harmonious neighborhoods

Housing has thus become a red-flag emergency, undermining the foundations of our democracies. The right to housing is a human right. The European Union is taking action and has included affordable housing among the pillars of its social cohesion policy.

A few weeks ago, the Commission announced the launch of the first housing plan for 2026, the European Affordable Housing Plan. The plan, designed to promote affordable housing, integrates with three other programs that aim to improve energy efficiency and make the ecological transition more humane, creative and participatory. This includes paying attention to the aesthetics and livability of the neighborhoods undergoing renovation. The goal is to increase the supply of affordable housing for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged groups.

The plan includes, among other things, the renovation of around hundred “Lighthouse Districts” – neighborhoods featuring affordable housing and services to improve the quality of life for local communities. By 2030, the construction sector could bring 35 million renovated buildings to the market and up to 160,000 new jobs related to renewable energy.

The Commission and the European Investment Bank (EIB) also announced collaborations with several European financial institutions to finance affordable and sustainable housing. The goal is to create a pan-European initiative bringing together local and national, public and private stakeholders to secure financing under the next housing plan.

The institutions in the field

Beyond official declarations, since when did institutions begin to consider decent housing a fundamental right for citizens?

“Eight years ago”, explains Bianca Faragau, EIB Institutional Policy Officer, “the European Pillar of Social Rights included housing assistance in Principle 19, specifying that access to good-quality social housing must be guaranteed. The mid-term review of EU cohesion policy in the current programming period introduces social housing for the first time as a new priority to be supported with cohesion grants, particularly through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF)”.

In practice, what projects were funded? And what investments were made?

“Over the past five years”, explains Faragau, “we have allocated 15.6 billion euros to finance sustainable and affordable housing. During this period, we have supported the construction of 265,000 new homes, renovated 400,000 home and provided housing for 665,000 families. In June 2025, the EIB Group launched an action plan for affordable and sustainable housing. Within this framework, we aim to increase housing lending to 4.3 billion euros by 2025. For example, in Italy, a 300 million euro co-investment programme was financed with Cassa Depositi e Prestiti to support the construction and renovation of social housing for students and seniors. The European Investment Fund and CDP are each committing 50 million euros to the Generation fund to create 2,800 places in student housing in Naples, Padua, Florence, Bologna and Parma”.

The current contribution of the cohesion funds

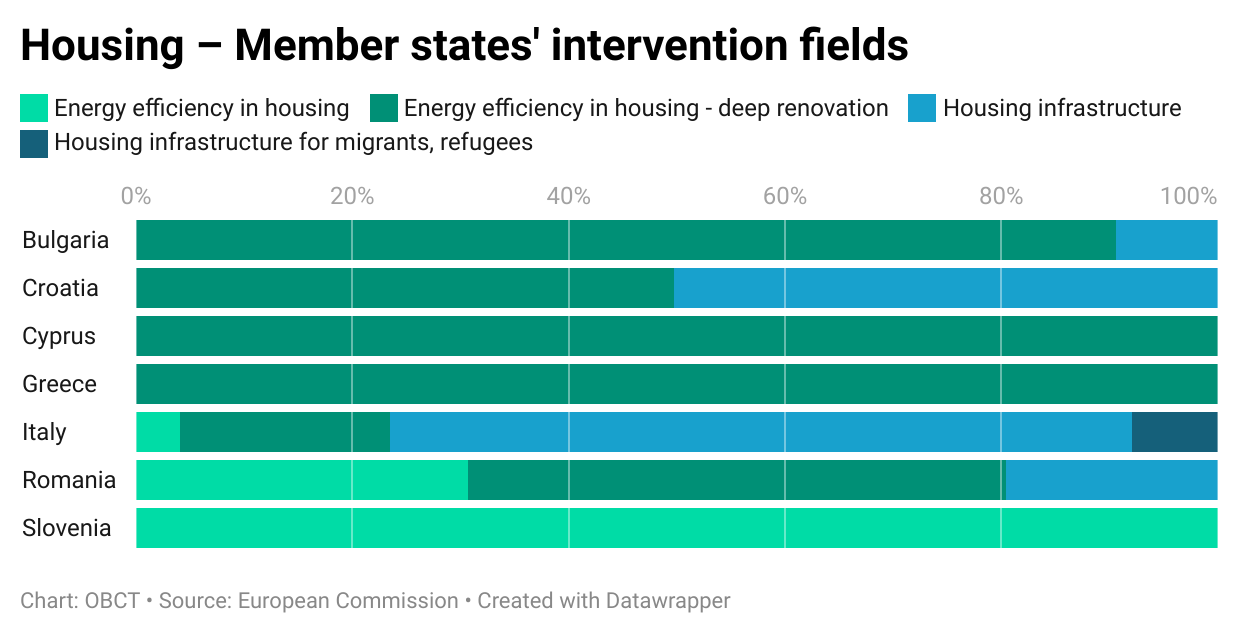

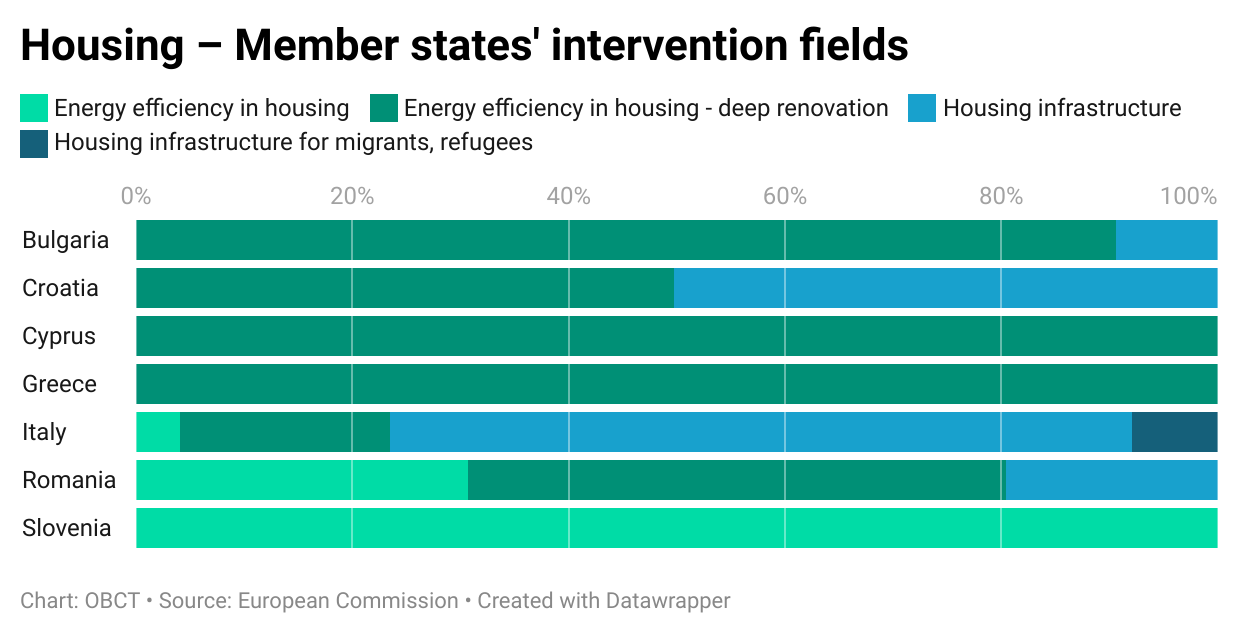

Cohesion Policy has allocated a total of 7.5 billion euros to the housing emergency in member countries, representing 2% of the total budget for the current seven-year period. However, this funding falls short of meeting current housing needs. The available funds are primarily aimed at improving energy efficiency, renovating and building homes for vulnerable groups (including migrants and refugees).

Nearly two-thirds of these resources fall under the ERDF regional funds, which are managed directly by the member states, in line with the priorities defined by national operational programs. As the chart illustrates, Italy is among the leading EU countries that has focused on building housing infrastructure. Slovenia has focused on energy efficiency, while Greece and Bulgaria are focusing on building renovation.

For its part, the European Economic and Social Committee, in a recent opinion, called for a greater commitment from European cohesion policy to address the housing crisis, to avoid serious consequences for the Union’s competitiveness.

While cohesion funds should provide a framework for new affordable housing solutions, the EIB must play a central role in developing financial instruments to address the needs of Europe’s regions.

The municipality of Vidin on the banks of the Danube in northwestern Bulgaria has 85,000 inhabitants and a significant Roma minority. The town faces daily socioeconomic challenges, demographic decline, unemployment and a lack of prospects for the future.

Thanks to nearly two million euros in European funding, a social housing project with 37 new apartments for the most disadvantaged groups was inaugurated in Vidin in 2023. The conditions for greater regional integration of beneficiaries have been created, ensuring their access to healthcare and education facilities.

Appeals from local associations

The European institutions’ intentions are noble, but the path to eradicating homelessness by 2030 is uncertain. Doubts are already arising over the definition of “affordable housing”. According to the EIB, housing is affordable when it meets an adequate quality standard, is made accessible at below-market prices and aims to support citizens who, due to income or social constraints, are unable to secure housing at market conditions”.

However, the European network of associations dealing with homeless people, FEANTSA, is throwing a stone in the pond.

The 2025 report states that “the concept of affordable housing is deeply ambiguous. It may appear at the first sight to be the obvious answer to housing exclusion, but in practice, it is often interpreted in ways that raise concern. In the European discourse, affordable housing is often conceived as a market segment aimed at middle-income households, distinct from social housing reserved for the most disadvantaged”.

“In several countries”, continues the report, “this shift in terminology has coincided with a gradual reorientation of housing policy toward market-driven approaches and a shrinking supply of homes for the most disadvantaged. The risk is that public funds are channeled into an intermediate segment to stimulate private investment, while genuinely low-rent housing, which is essential for meeting all needs, is neglected”.

Another social group affected by rising housing prices is university students and young researchers. A memo drafted by the European University Association emphasises that the European Affordable Housing Plan should “include student housing in EU housing strategies, promote targeted investments to support universities and local authorities, and foster partnerships between universities, cities, local governments and private investors”.

There are also some disturbing cases of ignored deaths. According to the Collectif les morts de la rue (a Parisian committee active on the streets of French cities), 912 homeless deaths were recorded in France in 2024, a 16% increase over the previous year.

“Housing issues”, states the 2025 report, “go beyond social, financial and economic concerns. They also include territorial, demographic, climate, environmental, cultural and legal aspects. Faced with housing challenges, a policy that is both comprehensive and rooted in the local community is essential”.

This publication has been produced within the EuSEE project, co-funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting authority and the European Union cannot be held responsible for them.

Tag: Coesione europea | EuSEE

Featured articles

- Take part in the survey

Home sweet home, a human right. But not for everyone

Four hundred thousand homeless minors, apartments at unaffordable prices, families living in the cold. Housing has become a luxury. The EU is taking action to ensure compliance with one of the principles of cohesion policy: affordable housing

© beeboys/Shutterstock

© beeboys/Shutterstock

In 2024, 1.3 million people in Europe were homeless. That is 20 out of every 10,000 inhabitants. Among them, 400,000 children. In the United States, a country often referred to as the nation of the homeless, there were 770,000 homeless people. That is 23 out of every 10,000 inhabitants. These are stark figures, exposing a vulnerability we thought was unique to the United States.

However, housing difficulties are not limited to those without a home. They affect a large segment of the European population: those struggling to make ends meet to pay rent and bills, those forced to live in unhealthy housing, and the 47 million who cannot heat their homes. Added to this are rising prices caused by the frenzy of short-term rentals and the resulting housing shortage. From 2010 to 2024, housing costs have risen by 48%, while wages have stagnated. Renting an apartment in Paris costs an average of 48.8 euros per square meter, just over 30 euros in Rome, Berlin and Milan, compared to 17.1 euros in Athens. The reality is often far from an ideal world where, to avoid housing cost overburden, one should spend no more than 40% of one’s income on housing costs, including rent, mortgage, utilities and maintenance.

Sustainable, functional and harmonious neighborhoods

Housing has thus become a red-flag emergency, undermining the foundations of our democracies. The right to housing is a human right. The European Union is taking action and has included affordable housing among the pillars of its social cohesion policy.

A few weeks ago, the Commission announced the launch of the first housing plan for 2026, the European Affordable Housing Plan. The plan, designed to promote affordable housing, integrates with three other programs that aim to improve energy efficiency and make the ecological transition more humane, creative and participatory. This includes paying attention to the aesthetics and livability of the neighborhoods undergoing renovation. The goal is to increase the supply of affordable housing for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged groups.

The plan includes, among other things, the renovation of around hundred “Lighthouse Districts” – neighborhoods featuring affordable housing and services to improve the quality of life for local communities. By 2030, the construction sector could bring 35 million renovated buildings to the market and up to 160,000 new jobs related to renewable energy.

The Commission and the European Investment Bank (EIB) also announced collaborations with several European financial institutions to finance affordable and sustainable housing. The goal is to create a pan-European initiative bringing together local and national, public and private stakeholders to secure financing under the next housing plan.

The institutions in the field

Beyond official declarations, since when did institutions begin to consider decent housing a fundamental right for citizens?

“Eight years ago”, explains Bianca Faragau, EIB Institutional Policy Officer, “the European Pillar of Social Rights included housing assistance in Principle 19, specifying that access to good-quality social housing must be guaranteed. The mid-term review of EU cohesion policy in the current programming period introduces social housing for the first time as a new priority to be supported with cohesion grants, particularly through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF)”.

In practice, what projects were funded? And what investments were made?

“Over the past five years”, explains Faragau, “we have allocated 15.6 billion euros to finance sustainable and affordable housing. During this period, we have supported the construction of 265,000 new homes, renovated 400,000 home and provided housing for 665,000 families. In June 2025, the EIB Group launched an action plan for affordable and sustainable housing. Within this framework, we aim to increase housing lending to 4.3 billion euros by 2025. For example, in Italy, a 300 million euro co-investment programme was financed with Cassa Depositi e Prestiti to support the construction and renovation of social housing for students and seniors. The European Investment Fund and CDP are each committing 50 million euros to the Generation fund to create 2,800 places in student housing in Naples, Padua, Florence, Bologna and Parma”.

The current contribution of the cohesion funds

Cohesion Policy has allocated a total of 7.5 billion euros to the housing emergency in member countries, representing 2% of the total budget for the current seven-year period. However, this funding falls short of meeting current housing needs. The available funds are primarily aimed at improving energy efficiency, renovating and building homes for vulnerable groups (including migrants and refugees).

Nearly two-thirds of these resources fall under the ERDF regional funds, which are managed directly by the member states, in line with the priorities defined by national operational programs. As the chart illustrates, Italy is among the leading EU countries that has focused on building housing infrastructure. Slovenia has focused on energy efficiency, while Greece and Bulgaria are focusing on building renovation.

For its part, the European Economic and Social Committee, in a recent opinion, called for a greater commitment from European cohesion policy to address the housing crisis, to avoid serious consequences for the Union’s competitiveness.

While cohesion funds should provide a framework for new affordable housing solutions, the EIB must play a central role in developing financial instruments to address the needs of Europe’s regions.

The municipality of Vidin on the banks of the Danube in northwestern Bulgaria has 85,000 inhabitants and a significant Roma minority. The town faces daily socioeconomic challenges, demographic decline, unemployment and a lack of prospects for the future.

Thanks to nearly two million euros in European funding, a social housing project with 37 new apartments for the most disadvantaged groups was inaugurated in Vidin in 2023. The conditions for greater regional integration of beneficiaries have been created, ensuring their access to healthcare and education facilities.

Appeals from local associations

The European institutions’ intentions are noble, but the path to eradicating homelessness by 2030 is uncertain. Doubts are already arising over the definition of “affordable housing”. According to the EIB, housing is affordable when it meets an adequate quality standard, is made accessible at below-market prices and aims to support citizens who, due to income or social constraints, are unable to secure housing at market conditions”.

However, the European network of associations dealing with homeless people, FEANTSA, is throwing a stone in the pond.

The 2025 report states that “the concept of affordable housing is deeply ambiguous. It may appear at the first sight to be the obvious answer to housing exclusion, but in practice, it is often interpreted in ways that raise concern. In the European discourse, affordable housing is often conceived as a market segment aimed at middle-income households, distinct from social housing reserved for the most disadvantaged”.

“In several countries”, continues the report, “this shift in terminology has coincided with a gradual reorientation of housing policy toward market-driven approaches and a shrinking supply of homes for the most disadvantaged. The risk is that public funds are channeled into an intermediate segment to stimulate private investment, while genuinely low-rent housing, which is essential for meeting all needs, is neglected”.

Another social group affected by rising housing prices is university students and young researchers. A memo drafted by the European University Association emphasises that the European Affordable Housing Plan should “include student housing in EU housing strategies, promote targeted investments to support universities and local authorities, and foster partnerships between universities, cities, local governments and private investors”.

There are also some disturbing cases of ignored deaths. According to the Collectif les morts de la rue (a Parisian committee active on the streets of French cities), 912 homeless deaths were recorded in France in 2024, a 16% increase over the previous year.

“Housing issues”, states the 2025 report, “go beyond social, financial and economic concerns. They also include territorial, demographic, climate, environmental, cultural and legal aspects. Faced with housing challenges, a policy that is both comprehensive and rooted in the local community is essential”.

This publication has been produced within the EuSEE project, co-funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting authority and the European Union cannot be held responsible for them.

Tag: Coesione europea | EuSEE