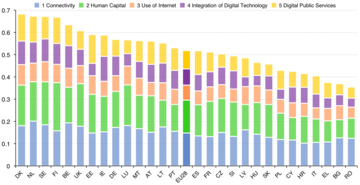

According to the data recently released by the European Commission, the EU member states in Southeastern Europe are among the least digital in the continent

The DESI, the "Digital Economy and Society Index", is an index which summarises many indicators on the digital performance of the EU member states. Its 2016 edition has recently been published, summarising the data collected in 2015.

In order to analyse the performance of the Balkan states belonging to the EU (Slovenia, Croatia, Greece, Bulgaria and Romania), it is interesting to compare them with Italy and Denmark, the top-scoring country.

In general, the EU member states situated on the Balkan peninsula score below the European average. The three worst performing countries are Romania, which occupies the last place, followed by Bulgaria and Greece. Then comes Italy, closely followed by Croatia. Slovenia is the best-performing Balkan country, number 18 in the whole European Union. However, it still lags behind the EU average in virtually all the indicators.

All the Balkan countries (and Italy) lag substantially behind Denmark, the top-scoring country, in all the dimensions of the Index: "Connectivity", "Human Capital", "Use of Internet", "Integration of Digital Technology" and "Digital Public Services".

Slovenia does well when it comes to the "Integration of Digital Technologies", which measures the digitalisation of business and their exploitation of online sales channels, being above the European average and in fact occupying the 11th position in the EU. Ljubljana also scores well in its levels of IT skills: 51% of the Slovenians can count on basic digital skills. However, the country scores poorly in "Internet Usage" (24th in the ranking) and "eGovernment", which concerns, for instance, the digitalisation of public services. In fact, Slovenia is the poorest scoring country in the EU when it comes to access to open data, showing a noticeable gap in its levels of access to information.

Croatia, the second-best scoring in the Balkans, does not score above the European average in any general criterion. It does so only in some sub-indicators, such as "Selling online" and "Selling Online Across Borders". It lags significantly behind in "Internet usage" (66% of the Croatians, against 76% in the EU and 93% in Denmark), and especially in "internet subscription to high-speed connections", where only 2.8% belong to this category, against a EU average of 30%.

Occupying the fourth worst position is Italy. Doing worse than Slovenia and Croatia, it is also the poorest scoring among the so-called Western European countries. However, compared to the previous year, Italy has shown little improvement in virtually all the categories, except "eCommerce in SMEs", where 8.2% of these enterprises make use of this digital resource. Italy has also a low adoption of high-speed connections, especially due to the general low IT-skill level of its population: 37% of the Italians do not use the internet regularly.

Following Italy comes Greece, which could do better in many categories. 34% of the Greeks do not subscribe to any kind of broadband connection, while 30% have never used the internet. Its number of regular users, 63%, is also among the lowest in the EU. Also, the volume of online public services is among the lowest in the Union, although there was improvement from last year's performance.

Finally, in the end of the spectrum, we see Bulgaria and Romania. Both countries suffer from a lack of digital skills: 35% and 32% of their populations, respectively, have never used the internet, the highest numbers in the European Union. Besides, only 31% of the Bulgarians and 46% of the Romanians posses basic or higher levels of digital skills. Both countries also have a long way to go when it comes to businesses making use of digital possibilities, as well as the use of digital platforms for public services.

This publication has been produced within the project European Centre for Press and Media Freedom, co-funded by the European Commission. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso and its partners and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The project's page

Southeastern Europe: not very digital

Southeastern Europe: not very digital

All the contents on the Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso website are distributed with a

All the contents on the Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso website are distributed with a