fdecomite/flickr

On November 10th, 1989, Bulgaria sees the end of Zhivkov and the single party. The events of that year, the ethnic question, and the attempts at lustration in an interview with Zhelyu Zhelev, philosopher and dissident in the years of the regime and first democratically elected president after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Philosopher and dissident, Zhelyu Zhelev was the first democratically elected president of post-communist Bulgaria. Born in '35, he was expelled from the Communist Party and marginalized because of his political convictions in 1965. As 1989 drew closer, Zhelev played an important part in the creation of the Alliance of Democratic Forces, which united the oppositions to the regime, and became its first president.

After the removal by the Politburo of Todor Zhivkov, the longest-standing communist dictator in Eastern Europe, on November 10th 1989, Zhelev led the Round Table which, following the Polish model, laid the foundations for a new, democratic Bulgaria. President of Bulgaria from 1990 to 1997, Zhelev is now president of the Balkan Political Club, an association which promotes the European integration of Balkan countries.

What kind of relationship was there between the democratic opposition and communist leaders before and after the fall of the regime? What was the impact of the opposition's actions on the overthrowing of Todor Zhivkov by the Politburo, on November 10th, 1989?

As the democratic opposition, we did not have any contact with the leaders of the Bulgarian Communist Party.We did not have open channels of communication even with the reformist elements.The first contacts happened, but only out of necessity, when the opposition and the regime began round table meetings,to discuss the dismantling of the communist totalitarian regime. And the opposition successfully demanded that the first topic be ending the communist regime. Before that, we had a very difficult struggle concerning the character of the round table discussions. Because the table's geometric shape is one thing, its political shape, another.

The Communists wanted all of us to sit together, as if we were in a casual meeting in a bar. We responded that there must be two separate positions: the government on one side, and the opposition on the other side. We did not seek an abstract compromise, but political negotiations on how to break down, dismantle, and eliminate the communist regime. And, we succeeded!

With regards to the coup against Zhivkov, I underscore that not one of us had any contact with the persons who had organised the overthrow of the internal leadership of the Communist Party, because Zhivkov's overthrow was a coup inside the party.

However, the democratic opposition, which was already born and active, was nevertheless one of the major factors which led to the fall of Todor Zhivkov. The other factor was the ethnic Turks in Bulgaria,who in May of 1989 started a series of hunger strikes by not hundreds, but thousands of people, in the villages and areas populated by ethnic Turks.

When did you understand that the regime was about to fall? Can we talk of revolution in Bulgaria?

People started to protest openly, to criticize and to rally in the streets and the Communists, in order to regain political and strategic control from the hands of the emerging opposition, decided to topple Todor Zhivkov. In this way, on the one hand, they again had the initiative, which is very important in political struggle. On the other hand, the more liberal elements inside the Communist Party showed up in the streets as heroes, who ousted the tyrant and opened the way for democracy.

However, all of this lasted only 40 days. On 14 December 1989, the streets in front of the Parliament were full of activists of the newly created Alliance of Democratic Forces,which united all the organizations from the opposition, intellectuals, and even officials of the nearby ministries. The protest had a very harsh tone, and the crowd asked not only cancellation of Article 1 from the Constitution, which provided for the leading role of the Communist Party, but also demanded resignations of the parliament and the government. All Communist Party leaders that tried to talk to the masses were booed and called "killers", "scoundrels". People shouted, "Bring them down!". We, the leaders of the opposition, hardly managed to hold the mass in order to avoid violence, which would have meant blood at the very birth of Bulgarian democracy.

Some extremist factions thought that by doing this Bulgaria lost the chance to have its own "velvet revolution", which is nonsense. We had neither money, banks, nor weapons. Even the hunter's shotguns were controlled by the communists. How could we fight by force a regime of such a type?At the time, we did not even have a room with a telephone to connect to the rest of the country...

You contested the very foundations of the communist regime when it still looked solid, and you were marginalised and exhiled. Did you expect to see its end, one day? What impressed you the most in the end of communism?

I knew, I was rationally convinced, not by rumours or by the emotions stirred by the events, that the communist regime was destined to end, because it was artificial. Long ago, communism demonstrated its inability to compete with the West. Communism could not compete economically, politically, socially, or in any other aspect. The West won the battle on all fronts.

The inconsistency of communism has become completely evident. However, I did not know when the regime would fall. Personally, I thought, as did many other friends and colleagues, that our generation would probably not see the end of communism, but perhaps our children would. However, we were nevertheless sure that communism would fall.

I also believed that the end of communism would be very violent with civil wars, protests, repressions, mass murder and terror; because Communism appeared to be a solid regime, which did not seem susceptible to attack from any direction.

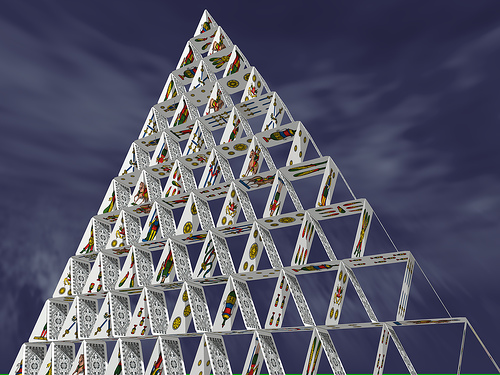

History, however, turned out to be an ironic teacher, showing how, even though on the outside the regime seemed solid, on the inside it was hollow and its political and moral foundations were rotten. All of a sudden, the entire system collapsed. I was very surprised by the fact that the communist regimes in Eastern Europe fell one after another like houses of cards, some of them even simultaneously. I could never have imagined that a totalitarian regime could collapse so easily.

The Bulgarian 1989 was marked, even before the fall of the socialist system, by dramatic discriminations against the Turkish minority, leading to the forced migration of 360,000 people (the so-called " "). How did the democratic opposition address the ethnic question?

From the very beginning, the Bulgarian opposition was immunized from the virus of nationalism. Zhivkov and his regime used nationalism, which they stirred in Bulgaria, pitting ethnic Bulgarians against ethnic Turks, a criminal policy for which Zhivkov should have gone to prison. However, at the time, we did not have the strength to arrest him.

From this point of view, from the very emergence of the opposition structures, we managed, by having a firm position on the issue of ethnic Turks in Bulgaria, to give a strong anti-nationalistic spirit to the opposition and to condemn Zhivkov's policy as anti-national and criminal with regards to human rights, in addition to being internationally isolationist.

By this categorical position, we succeeded in creating a common front with the resistance from the Turkish community; something which proved extremely important. Moreover, because of this, Bulgaria did not have events such as in nearby Yugoslavia. At that time, the Serbian opposition in Belgrade had huge protests led by Draskovic and other leaders, but the opposition did not free itself from the spirit of nationalism, Serbian nationalism and chauvinism. When it came to taking a position on Milosevic and the Federal Army, exactly because of nationalism, which by then was out of control, the opposition capitulated, and stopped being an important political factor. Many of the opposition aligned with Milosevic in the wars against the other republics, which resulted with the crimes we all know.

After 1989, many Eastern European countries tried to carry on a lustration process towards those who had supported the repression system of the totalitarian regime. What was your position in this regard?

We wanted to have lustration in Bulgaria, in order to remove from power those who supported the communist regime and who had taken part in the politics of terror over the Bulgarian people. We wanted a new system free from the political influence of these communist functionaries, without having to kill or terrorize them in turn.This was possible, and many of us supported this solution in the political transition from one system into another.

There were, however, also in the opposition, those who felt that it was not just to reach for extreme solutions. However, if we had had lustration, many things would have been clearer. The entire issue of the regime's files and their publication would have had an entirely different meaning: it would have been a catharsis for Bulgarian society.

It would have been known who has collaborated with the secret services; who had committed terror, directly or indirectly; and who had served the interests of the regime with repression against all the people. However, at the end, lustration did not take place. Also, the Council of Europe was not much in favour of the idea, because this also has anti-democratic aspects. When a part of society, irrespective of its nature, is excluded from political life, without a trial and a verdict, this is opposed not only to political values, but also to the principle of rule of law invoked by the Council of Europe.

Many countries of the former Soviet bloc currently show elements of nostalgia for the communist regime, even among the younger generations. Why do you think this happens?

When a person lives in a certain system, and he/she helps construct it in his/her youth, this is for them a romantic period, when they have demonstrated their abilities and achieved many things, reaching successfully their personal goals. Given that a lot of time has passed, they remember it as a romantic world, beautiful and just, and this naturally applies primarily to the old generations.

When young people talk about communism with nostalgia, they repeat the things they have heard from their parents or perhaps grandparents, who tell them, "how beautiful it was back then". However, if these young people try to think of the possibilities they have today, compared to those from back then, the fact that they can travel the world, study or work abroad, have a career in America, Germany, or the UK, wherever their interest takes them, and to the full extent of their abilities.

Whereas during communism, when we lived closed in a concentration camp, no one could go anywhere, unless they were part of the caste of the communist elite, which could travel the world as a privilege. Otherwise, they had to stay here and watch their abilities slowly shrivel...